The Brown Man’s Burden

/In that year, the Filipinos established the first Asian Constitutional Republic, expressing their national will and overthrowing the 333-year reign of the Spanish in what should have been their sovereign country. Instead, they were obliged to wage a new war against the new American invaders, who had racist issues of their own.

My great grandparents on both sides were touched by these conflicts. They were testimony to the fact that the ilustrados (who did not necessarily had to be wealthy but were marked for their being enlightened and educated) did not stand aside but were active in the Revolution. The latter was not solely a proletarian affair but put to use the brains and even the brawn of people like the Lunas, del Pilars, Alejandrinos, Tinios, and Llaneras.

On my father’s side, the ancestral home in Maragondon, Cavite of Roderico Reyes and Juana Viray had been commandeered to serve as the trial venue for the hero Andres Bonifacio. While they may have been supporters of the Revolution, they were forced to flee to their mountain home during this event.

Maragondon, Cavite Reyes Ancestral Home

Author at his ancestral home in Maragondon, Cavite

Bonifacio Trial House with Bunting

On my mother’s side, my great grandfather Felipe Tempongko had actually fought in Aguinaldo’s Army of the Republic.

Lolo Felipe “Peping” Tempongko passed away in 1945 and thus was gone by the time I entered the world four years later. What I knew of him were mainly stories passed on by the gatekeepers of family history, his daughter and my grandmother, Esther, as well as my own mother, Erlinda. My mother, for instance, remembered having met President Emilio Aguinaldo around 1939 in his Kawit, Cavite home. He still clearly recalled Felipe Tempongko as having been active among his troops.

Lolo Peping was born in 1873 to prosperous Binondo residents, when the Spanish Empire in the Philippines was being challenged by native political stirrings, culminating in the execution of Jose Rizal and the Revolution’s outbreak in 1898.

A student at San Juan de Letran College in Intramuros (which celebrates its 400th year in 2021), he studied fencing at the studio of Antonio and Juan Luna on Azcarraga Street in Sta. Cruz, Manila. This may have led him to enter the Oriental Lodge of the Masonic Order, where he eventually achieved the rank of33rd degree.History teaches us that the Masons played a significant role in the Philippine Revolution, not only in its membership, but also in its rites and recruitment procedures.

Felipe Tempongko in Top Hat, Center, as Masonic Official

Hence, it was not surprising that in 1899, Felipe Tempongko would abruptly leave his new wife, Leocadia, and fledgling family in order to fight among the ranks of President Aguinaldo’s troops. This was in the second phase of the Revolution, this time aimed at the new American invaders. He would be held captive by them and ordered to do menial chores until they realized that he would be more useful in clerical duties. He would then join a Committee organized by the Americans to help establish “peace and cooperation” in the Visayas. This included his own future brother-in-law, Dr. Joaquin Quintos, who would marry his sister Demetria; as well as such luminaries as Alejandro Albert, Carlos Ledesma, and Vicente Singson Encarnacion.

Felipe Tempongko in top row, second from right

Fortunately, some family pictures have survived to show us glimpses of this storied past. These include those of his own mother, Dona Inez Calixto y Ahchuy (whose Limoges porcelain set has also miraculously survived) as well as of his Calixto relatives.

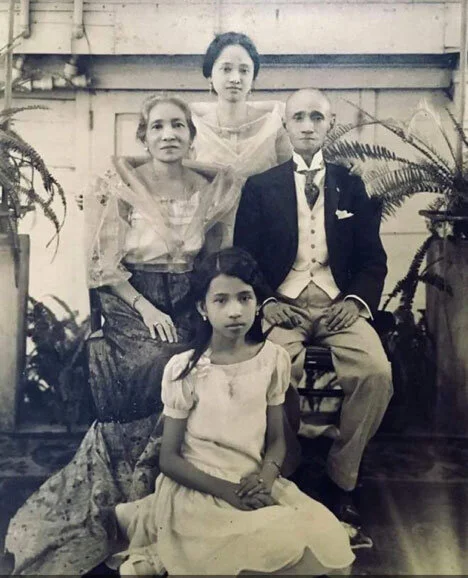

Felipe's uncle, Edilberto Calixto with his family

The Limoges China set of Inez Calixto de Tempongko

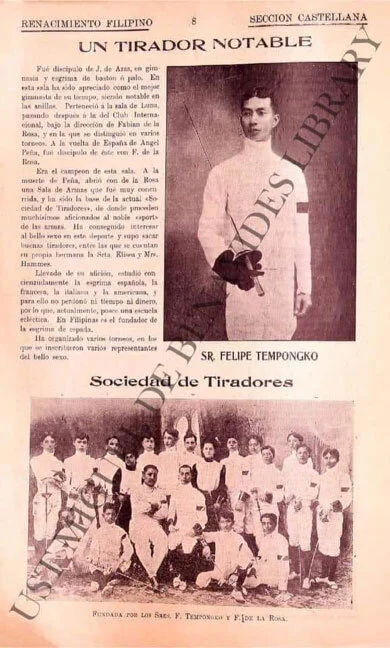

But the most precious one is an account recently unearthed during the lull of the pandemic in the depths of the UST Benavides Library, in a publication called El Renacimiento Filipino edited by Martin Ocampo. Published between 1910 and 1913 in Spanish and Tagalog, the magazine was unabashedly anti-American. Many intellectuals subscribed to it and it would be cited in the famous case called “Aves de Rapina’’(or Birds of Prey) in which the American scholar Dean Worcester accused the writer Teodoro M. Kalaw of slander.

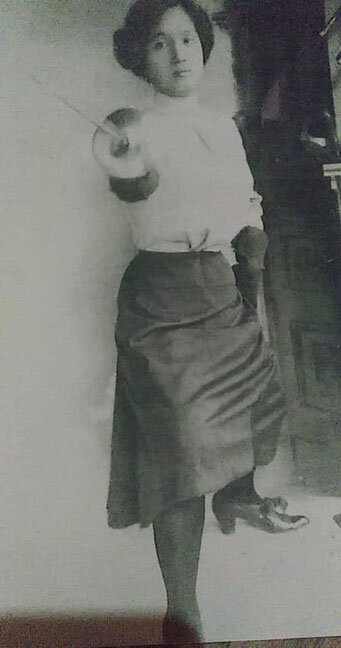

The article describes Felipe Tempongko as “un tirador notable” or “an outstanding fencer.” It noted that he belonged to Luna’s school and that, together with the artist Fabian de la Rosa, he opened a fencing school, which trained many Philippine fencers and even members of “the beautiful sex” including his own sister Elisea and a certain Mrs. Hammes. Not mentioned in the article is that he trained his own daughter, Esther, in fencing as well. He is thus considered the founder in the Philippines of sword-fighting and as having trained its first women sword fighters. This considerably moves back the history of fencing in the Philippines, which only records its beginnings in the 1950’s with the Dayrit brothers.

Elisea Tempongko (Macapinlac), first lady fencer of the Philippines

The Americans knew how to mollify the Filipinos, who loved pageantry and finery. They quickly organized the Philippine Carnival modeled on New Orleans’ Mardi Gras in 1908. In the court of the first Carnival Queen, Pura Villanueva (later Kalaw) were two of Felipe’s sisters, Elisea and Purificacion, and his brother, Clodualdo.

Clodualdo Tempongko, far left, with a squash hat, and at opposite end, sisters Elisea and Purificacion, third and fourth from right

Curiously, although Felipe Tempongko passed on his skill to his sister and daughter, he never trained his own sons in fencing. Was that a cautionary tale on not undertaking a sport that would be futile in case of another invasion? In point of fact, even in advanced age, Felipe Tempongko kept up his physical exercises for fencing in his home on Vermont St. , Malate.

The family of Felipe Tempongko and Leocadia Lheritier in their Malate home

The years 1910-1941 were to be fondly remembered by postwar Filipinos as “peacetime.” Indeed, Felipe Tempongko and his wife, Leocadia L’heritier, were to raise a robust family of nine children. While being a stalwart of the Nacionalista Party (he was a ward leader in Manila, briefly appointed Councilor, and unsuccessfully ran for a minor political office), he settled on being a punctilious accountant head at La Estrella del Norte on the Escolta. He ultimately found his happiness in domesticity. Until the Second World War came.

Felipe Tempongko's large brood of nine with friends “in peacetime.”

Driven from their final home in Paco by American bombs and Japanese firepower, the erstwhile revolutionary in 1899 was forced to turn over his antebellum binoculars to roaming Japanese soldiers, a last souvenir of his glory days. His fencing skills were of no use in this context.

His wife, Leocadia, hit by a shrapnel in the first bombing of Paco, died in February 1945, a few weeks short of what would have been their 50th wedding anniversary. He would only survive her by a few months, a death aggravated by heartbreak.

A career diplomat of 35 years, Ambassador Virgilio A. Reyes, Jr. served as Philippine Ambassador to South Africa (2003-2009) and Italy (2011-2014), his last posting before he retired. He is now engaged in writing, traveling and is dedicated to cultural heritage projects.

More articles by Ambassador Virgilio Reyes, Jr.