Petite Peso, and Why Not?

/Petite Peso (Photo by Topo Chico)

Chef Ria is aware that pocketbook worries are at the root of unexamined assumptions that Filipino dishes, when cooked correctly, all taste the same. Petite Peso entrees range from $8 to $14.

“I always ask our cooks to pretend you’re making each dish for your parents, grandparents or favorite person,” says Chef Ria. “Is it something you’re proud of? Would you spend your hard-earned money on it? I don’t believe in the concept of a VIP because to me, each person who walks through our doors and spends their precious time and resources is a valued guest and we should always put forth service and food that’s representative of Peso hospitality.”

Karma Jam on Toast

Chef Ria was first featured in Positively Filipino in 2015. At the time, she was operating her own WILD restaurant part-time at Canelé (closed in 2017) in Atwater Village. The article lists the education and kitchen background behind her irreproachable pedigree. However, up until Petite Peso opened its doors on April 17, 2020, Chef Ria was perpetually paying her dues.

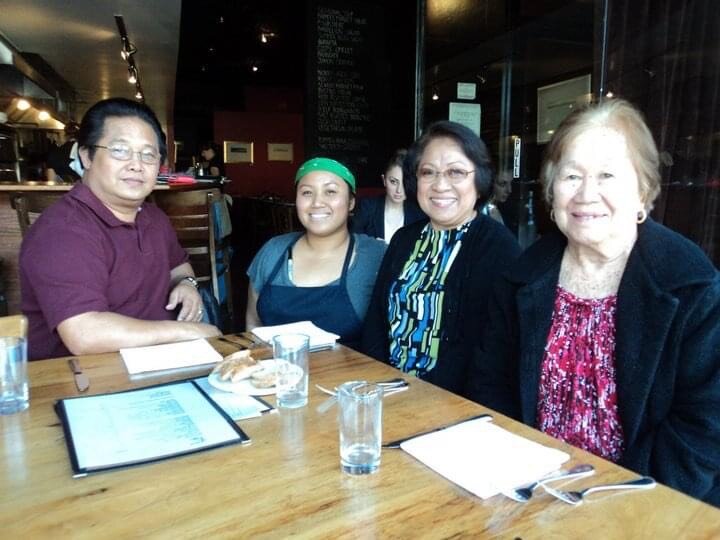

Barbosa and her Friends Cook at the now shuttered Canelé restaurant in Atwater Village. (Photo courtesy of Chef Ria Dolly Barbosa)

As the head chef during the golden years of Sqirl in Silverlake, her imaginative recipes helped bring Chef Jessica Koslow international acclaim. Restaurant critics fawned over Chef Koslow without questioning how the “Genius of Jam” could also have preternatural facility with pesto dishes. She could talk the talk and dishonestly walk the wok.

Six years after Chef Ria left Sqirl, a moldy jam scandal unraveled the myth of Chef Koslow and gave Chef Ria and fellow employees who toiled in obscurity a cup of justice after a decade of watching their employer take sole credit for their revolutionary creations.

Now that she runs her own kitchen, Chef Ria doesn’t look back in anger. “The biggest lesson I took from my experience there was to be respectful, truthful and transparent especially when it comes to giving credit where it is due,” she shrugs. For Asian Americans, she reveals the pitfalls when shams exploit the gratitude Asians feel for the opportunity to earn a living in a free country. These bogus idols only recognize the contributions of their worker bees when it makes them look magnanimous or after a customer slathers moldy jam on her toast. Sometimes, a peculiarly Asian belief restores order to a capricious world: Karma.

American Filipino Adobo

Firmly in charge of her destiny, Chef Ria makes no apologies for the enhancements she brings to traditional recipes. “I challenge what the notion of authentic is. It’s a slippery slope of gatekeeping because what is true, authentic adobo anyway? There are base similarities but,” she makes the claim that “there is no true, singular ‘authentic’ or ‘traditional’ recipe. My mom’s adobo is different from my dad’s and probably different from the next person’s. That is the beauty and exciting nature of regional cooking.”

In implying a distinct American regional style of Filipino cooking, “I can only speak for myself, and the perfect balance for me is evoking those familiar flavors and enhancing it with techniques and tricks I’ve learned along the way.”

This perspective is displayed in the dressings Petite Peso bottles for customers. “Our unique offerings piqued our guests’ interest because we’re taking these flavors we grew up enjoying and spinning it by using everyday American conveniences like a bright and citrusy lime bagoong salad dressing and toyomansi facelift to aioli for a Filipino spin on a BLT with, of course, replacing bacon with tocino. It’s a way to incorporate those flavors into the day-to-day condiments we’ve become accustomed to here in the U.S.”

“The adobo made with crispy chicken skin and coconut milk is the culmination of 20 years of subtle changes improvised by Chef Ria Dolly Barbosa.”

Doing Right by the Ingredients

At Petite Peso, Chef Ria sources her ingredients in ways that are likely to give diners a clear conscience. She says of the farm cited on the menu, “Mary’s Chicken is a family farm that specializes in free-range, humanely raised and handled chickens and most important, it is delicious. We love to use and highlight products with integrity. For the grain bowls and salads, we use Mary’s chicken breast and for the adobo rice bowl, we use Mary’s whole chicken legs.”

Petite Peso wants to be part of the solution in slowing down climate change but is also feeding optimism in these pandemic times. “As devastating as Covid was to all restaurants, it forced chefs and operators to rethink their approach,” observes Chef Ria. “It also forced diners and all of us, really, to seek comfort in an incredible time of uncertainty, and for a lot of us, we turned to making and wanting to eat comfort food. There is something about a bowl of kare kare, tinola, sinigang or munggo that seems to invoke promise of a silver lining in the midst of a pandemic storm.”

God forbid an incurable omega Covid variant to ravage civilization, Chef Ria has written down her last meal on Earth. “My last supper would consist of steamed Dungeness crab with lemon compound butter, grilled longanisa [Filipinos spell it with an ‘s’; Spanish speakers with a ‘z’.], steamed white rice, a cobb salad, elote, a crusty baguette with beurre de baratte and caviar, sans rival [Filipino dessert cake] and a Macallan 25 neat.” For those who question such exacting extravagance, she answers, “Why not? What better meal to go out on?”

Picture that Prix Fixe option that includes a $2,500 malt whiskey on the Petite Peso menu. Planning a last meal is a way to cherish the present and take account of the pleasures available today. No wonder as the economy opens and retreats, depending on coronavirus fluctuations and mutations, people—whether hedonistic or creatures of moderation—are crowding airports anyway. There are also modest places where cautious people can have a special experience without catastrophes looming.

Petite Peso’s Pork Lumpia (Photo by Topo Chico). See Chef Ria’s recipe in The Happy Home Cook: Pork, Shrimp, and Shiitake Lumpia.

Petite Peso’s Calamansi Drink (Photo by Topo Chico)

Petite Peso is located in the former Ricebar location at 419 West 7th Street in downtown Los Angeles. Takeout is highly recommended since the wait for any of the five tables can last 20 irretrievable minutes. Go to the Petite Peso website for hours, the current menu and other details. I repeat our friend’s question: Why not?

More on Chef Ria Dolly Barbosa:

[SIDEBAR]

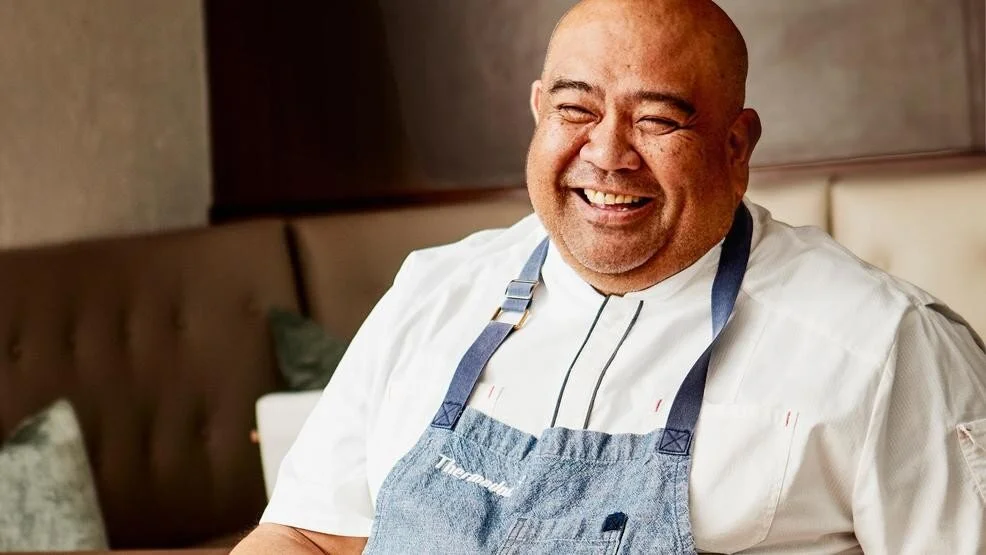

Chef Rodelio Aglibot, A Tribute

Chef Roger Aglibot (Source: WKRC)

Speaking of undying generosity, Anthony gives long overdue recognition to one such soul who passed away in March of 2020. Through the years, Chef Rodelio Aglibot was featured in Filipinas Magazine and Positively Filipino articles on Koi, Yi Cuisine, and Sunda, all pioneering restaurants that moved Filipino cuisine into the mainstream. Nicknamed “the Food Buddha” for his large dimensions and bald pate, Chef Rodelio was known by his food and for honoring a personal duty to mentor young Filipino men and women on the West Coast and in the Midwest on every aspect of restaurants from choosing a location to interior design to developing a menu to daily operations. New generations of chefs carry on his legacy of passing food and business knowledge to newcomers entering a profession with unsympathetic odds in a stressful, unrelenting industry. If he had lived longer, he would have realized his dream of building an national association of Filipino cooks. One of Chef Rodelio’s simple pleasures was cooking Spam for himself during midnight work breaks. When he started Koi in Beverly Hills, he enjoyed gabbing with the sushi chefs who taught him knife skills. All aspects of cooking mattered to him, and Asian food was his passion.

Anthony Maddela covers restaurants, Southern California, bird stuff and other topics from his home in Los Angeles. No, his family seldom gets a meal comped for his efforts, though the best, most successful chefs have been generous.

More articles from Anthony Maddela