On Newsmen’s Row

/Project 6, Quezon City

From my bedroom window, I would see a barefoot farmer and his carabao till the soil for another rice crop. Around his small tract of rice paddies were bamboo groves, creaking and hissing at the slightest breeze. It was a small pocket, a remnant of a scenery that was bulldozed to become Project Six.

The street names of Project 6 were Road 1 to Road 10 and Alley 1 to Alley 34. Roads were 15 meters wide and alleys were only six meters wide. The nomenclature retained the hand-drafted letterings of the original blueprints up to today. Only the then-uncompleted Mindanao Avenue on the north and Visayas Avenue to the south were given real names. These planned super highways were cut off by a tiny creek with no name that meandered west to the San Juan River. Our street ran parallel to that waterway.

Our neighborhood was fondly called Newsmen's Row. On the corner of Road 3 and Road 7 lived Primitivo Mijares of the Daily Express; then going on Road 7, there was Joe Aspiras of the Star Reporter and the Evening News, spouses Oscar and Alice Villadolid, of the Philippine Herald and the New York Times respectively; Teddy Benigno of Philippine Star, and Frankie Evangelista, the anchor of Channel Eleven News.

Road 3 was intersected twice by the wide-U-shaped Road 7. The newsmen starting from the lower intersection were Charlie Castaneda of the Evening News lived. Then going up, there was Mabini Centeno of the Evening News and a former president of the Malacañang Press Corps; and Nestor Mata, the Herald reporter who had refused to buckle up on an ill-fated flight; he was the sole survivor of the plane crash that killed all other passengers on board, including President Ramon Magsaysay.

The list goes on up Road 3 with poet-writer Manuel Bautista and his wife, Liwayway, a prolific writer, Liberato Marinas, Sr. of the Herald, Teodore Owen Jr. and Jesus Bigornia of the Manila Bulletin. Mr. Owen was one of the three impartial journalists who interviewed Benigno ‘Ninoy’ Aquino on “Meet the Press” in 1978. Everyone with a TV watched the then-incarcerated Ninoy live, take the tough questions and answer with fire inside him. His indomitable spirit made him the best president the Philippines never had.

Though not newspapermen, Rolando Sambile and my dad, Romeo Firme, also lived there. Together with Joe Aspiras, the three gentlemen married the Mendoza sisters.

The newspaper was the backdrop of the time our generation of children grew up together. The roads and alleys of Project 6 were our playground.

Photograph in black and white from the archive of the Villadolid family, showing their housing unit in Project 6, courtesy of Paula, the seventh of nine siblings.

Photo shows the bend at Road 7 where Oscar and Alice once lived. Note the unpaved gravel road and the three-bedroom bungalow replicated all throughout Project 6 in the mid-sixties. Before the end of the decade, the house was demolished completely and a sprawling brickwork home emerged that exists to this day.

The fire tree yearling on center left, was a silent witness that remained and matured. In the early ‘70s, we, the children of Newsmen’s Row, made “istambay” under its shade.

Pearl

The summer of 1970 was a long one. On top of the regular two vacation months of April and May, classes on the last days of March were suspended because of protests in the streets. Graduations were in limbo, summer classes suspended wholesale.

On Road 7 every morning after breakfast, we would gather by the shade of the fire tree on the Villadolids’ front lawn. Their mayordoma would bring out baby Mecca for sun bathing. My mother would sun our youngest siblings the same way. She explained to me that the gentle morning rays of the sun were with life-giving vitamins that gave the infant color.

The term “mayordoma” or the domestic head was adapted from our colonial past with Imperial Spain. It referred to the head caretaker of the children and household of the Insulares, the Spaniards born in the Philippines. She was usually a matronly Indio, a term the Español used to refer to Filipinos. She was likely intelligent, and a mother herself.

Mayordoma was a plump mama. She was kayumanggi -- a descendant of the brown-skinned migrants from the Indomalayan regions of Asia. She would sit on the same spot, on the carabao grass, with the baby niece of Alice. She always had a good “morneng” welcome smile on her face. One by one, we would join her and make istambay, a Pinoy street term for one who “stands by,” usually doing nothing.

We were barely in our teens. The oldest among us was the 17-year-old Aurora Benigno. The youngest, other than the baby, was the sweet ten-year-old, wavy black-haired Boyet, the youngest of the Mijares children.

We had a healthy mix of boys and girls. The girls would form their pack and the boys would follow them. They would play table tennis and we would join them. With our bicycles, we ventured all around Project 6. It was the best of times; the worst of times was inconceivable then.

Among the girls, Pearl Mijares stood out. I felt I was unworthy to even look at her.

She was the fairest of them all. Her skin was like porcelain. Her long curly locks were brownish like maize. She had naturally pink lips with a small mole on the upper left side of her mouth. With her sister, Pilita, they were like a pair of dolls custom-made for the aristocracy.

Aurora was my neighbor across the street. She would be enrolling as a freshman in UP later that June. One day that summer, she had the idea of donating sandwiches to the UP protesters. While we spread the egg salad on the Tasty, the name of a brand that Pinoys refer to as sliced bread, Aurora related that she was hanging around in Pearl’s bedroom a couple of days before. At one point, Pearl excused herself and went to the bathroom. Aurora saw her diary in the corner of the room and she started reading it. Aurora looked at me and said with a smile, “Pearl wrote an entry that she found you dashing.”

The revelation took me a moment to comprehend. I asked her, ‘Ahh, what do I do?’

“Tell her you love her, and when she answers that she loves you, you become boyfriend and girlfriend.”

That took much longer to sink in.

We soon finished packing the sandwiches and we hopped on a public utility jeep, a mode of transportation that originated with the GP or general-purpose vehicles the US army discarded everywhere during the WWII. We headed for the besieged University of the Philippines, Diliman campus.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

The Mijareses lived in the highest point of Road 7, by the corner of the main bus route on Road 3. They had a small beauty parlor business named Priz Beauty Box. I walked in as a customer, had my hair trimmed, and hoped that Pearl would come in. On the mirror’s reflection, I saw Boyet enter the air-conditioned room.

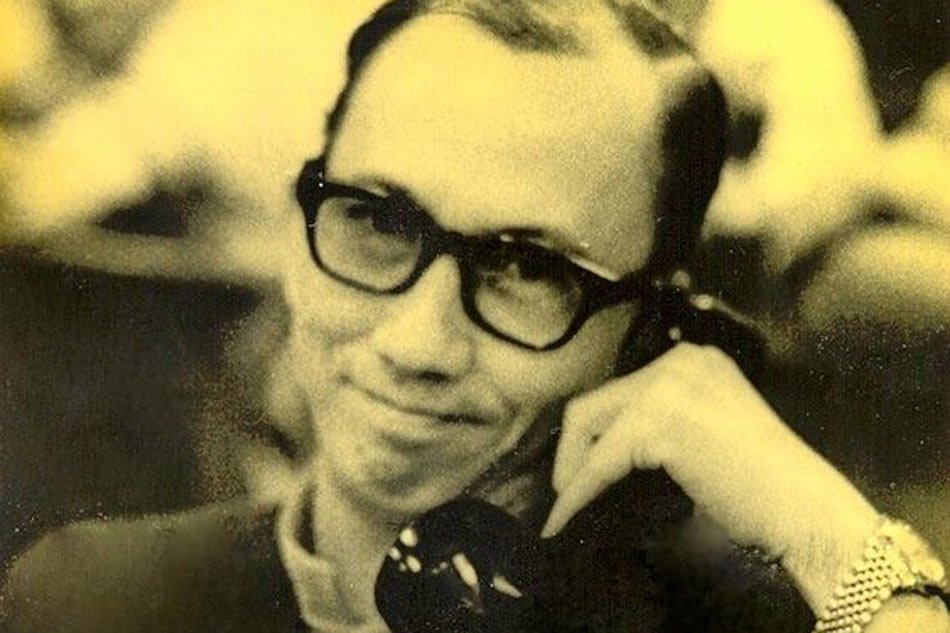

Primitivo Mijares (Source: ABS-CBN)

I connected with Boyet. I asked him first about his dogs. Then I requested him to tell his “Ate,” a Tagalog term for the oldest sister, a message, “Can you please tell Pearl that I would like to visit.”

His eyes brightened and with a boyish smile, he said “OK.”

My haircut was done when he came back in and said, “She will meet you at the garahe.”

Their four-car garage had two vehicles parked. In between the car spaces were clean laundry hung to dry in the warm summer air. I found a plastic pail, inverted it, and sat waiting as I whiffed the freshly moistened air infused by the scent of laundered fabric.

I quickly realized that I was in uncharted territory. Should I have dressed up? I still had hair cuttings on my sandals. What if...

Pearl parted two white sheets and found me. She was like a cool breeze. She said “Hi” and I was high in the clouds. Like myself, she did not know how to proceed and just stood in front of me.

I mentioned, “I just had a haircut”’

“I know,” was her answer.

I followed up, “This is my first time visiting a girl.”

“Me too,” she revealed it was the first time she was visited by a boy.

I stayed for a few minutes more, but had to go because I was running out of things to say.

Our daily rendezvous by the garage, curtains drawn with sheets hung to dry, went on for a few more afternoons.

“Among the girls, Pearl Mijares stood out. I felt I was unworthy to even look at her. ”

------------------------------------------------------------------

One visit after dusk on the street in front of their garage, we had our backs on their steel gate. I just looked up at the moon. It was a beautiful sight. I stuttered, “A-alam mo-o,” an awkward Tagalog for “you know.” I felt my throat tighten as I declared with difficulty, “I...love...you.” My head slightly swiveled to the right; my pupils moved faster to the same edge of the eye sockets. I sought a reaction.

After a second, she turned her head left to me and answered in Tagalog, “I'll get back to you, tomorrow.” I was sure she went up to her bedroom to write on her diary.

The next night, with the moon fully waxed, we continued where we left off. Our backs were again on their gate. I was quiet, transfixed at the bright celestial orb. Pearl said in a straight and sweet voice, “Alam mo... I love you too.”

My heart jumped with joy.

It was my turn to go to my bedroom and write on the diary in my mind. The entries would finally be written down in this memoir more than half a century later.

Puppy Love

Pearl and I were both the eldest child in our families. We had no clue on how to move forward, so we went underground. Our puppy love remained a secret. We groped on the concept of a couple; we were virgins of the relationship world.

My concern was her parents. “Who was that boy who visited Pearl?” was my guess on the conversation with her mom and dad at the dinner table. I was an interloper in the Mijares home.

Her father was the editor of the Daily Express, the propaganda newspaper of the Marcos administration. But Primitivo Mijares was more than that; he was a confidant of the president, and an enabler who slanted the headlines of the government-controlled newspaper. He was influential enough to get his lawyer wife, Priscilla, a presidential appointment as a trial court judge.

I hardly saw him. The only clues were the black and white family photos displayed in their living room. Primitivo was almost always out. He frequented Malacañang and was known to be one of the few who was allowed wake up the “Apo Lakay,” the Ilocano term of respect for an old leader.

I perceived Pearl’s mother as a stern disciplinarian. I imagined her sending people to jail. On one visit, shielded by bed sheets left to dry in the garage, we heard her call out loud, “Pearl.”

Pearl placed her finger on her lips and whispered, “Keep it quiet,” then she ran to her mother. I waited long for her to come back.

“We are going to the grocery, go home for now,” and she left me alone again.

We were discovered, the paranoid in me thought on my walk back home.

--------------------------------------------------------------------

One evening, Pearl and I walked together to a neighborhood teenage dance party at the Marinas residence several houses away. It was a typical three-bedroom bungalow replicated all over Project 6. It had asbestos roofing on concrete hollow block walls. This home was renovated to include more bedrooms on a second level extension at the rear. We used the covered garage as our dance floor.

We danced the night to only one long playing, 33 and 1/3 rpm album of Santana. Our handa or prepared party food was the ever-reliable “STP,” a play on the brand of a racing car additive. For us, STP stood for Spaghetti-tinapay-Punch, tinapay being sliced bread.

Everyone danced and pranced. Leonides, one of the Marinas twins, wore his mother’s black pearl necklace. It was long enough to reach his knees. While dancing to the African rock beat of “Devadip” Carlos Santana, I took the other end of the necklace and placed it on my neck. We were connected while we danced. Then I pirouetted. The necklace string broke and a hundred round plastic beads rolled everywhere. Some other dancers slipped.

Leonides and I were on our hands and knees, managing the spill. I only got back a handful of the pseudo black pearls.

“That’s OK, I’ll take care of this. Go back to the real Pearl,” said my friend. I just nodded and continued to party.

When the vinyl record reached the cut “Samba Pati,” it was just Pearl and I who slow-danced. It was the first time we ever held each other in close embrace.

We were both stiff and unsure.

I was old-schooled. “Do not touch the fruit until you’ve bought it,” was a saying my paternal grandfather, Florencio Sr., once warned me. The movies I watched with the house help were Pilipino Classics which portrayed the “Maria Clara,” a representation of the demure and conservative Filipina, where kissing on film was not done.

I did not cross the line, until that night.

By midnight, I walked her back home. On the same driveway, our lips bade each other good night. I then floated back to my bedroom.

Second generation ladies of Newsmen’s Row. Listing their maiden names from left to right, Teresa Villadolid, Aurora Benigno, Laura Centeno, Pearl Mijares, Pilita Mijares, Nanette Capinpin, and my sister Chona Firme. Picture was taken before an event where Pearl was crowned Queen of Batangas City.

(Photo from the library of Aurora Benigno. Photo restoration by digital artist Tiqui Del Rosario.)

The next day was another glorious God-given day of summer. After our debut the previous night, I got my bicycle and asked Pearl to join me for a spin.

Those bikes were made for a single user, not intended for passengers. We thought the frame at the back for a basket was for the angkas, the Tagalog for “hitch,” which became the term for the back rider. It was uncomfortable when the road got bumpy.

Pearl rode it without hesitation. She sat behind me and we passed by all the roads my muscles could carry us. I never wanted the ride to end. In spite of our physical closeness, she refrained from touching me. She just held on the metal rack.

I was thrilled to be with her. We were like two puppies.

We moved our visits to the open front porch of her home. There were two dog houses with corrugated steel roofing on the outer wall corner. We sat on the steel garden set and talked. “What are you thinking?” was a question I often asked that never got the same answer.

One afternoon before classes started, we were hanging around the same porch when Pearl heard a familiar car horn. Her mother, Priscilla, came home early that day. The house help ran to the gate and I saw her mom, seated behind her driver, through the gaps of drying laundry. The car parked behind the curtain of blankets.

Pearl ran to meet her mother.

I froze then walked to the parlor on the opposite end of the house without greeting her mom. I waited it out at the beauty shop until I ran out of topics to converse with the staff. Pearl never came back to me and I walked home thinking, I did something wrong.

“My mom said you are bastos,” a strong Spanish term adapted by Filipinos for discourteous, impertinent, or impolite. What made it worse was that I heard it relayed to me by Aurora.

I walked away from Pearl by evening.

---------------------------------------------------------------------

Forty-four years later, on the night of January 8, 2018, the ladies of Newsmen’s Row attended in full force and celebrated the milestone of Amparo’s 90th birthday at the Shangri-La ballroom in Makati. Priscilla Mijares and my mother, Fredesvinda, were seated on the same round table for ten. At some point, she intimated to my mom, “Sana sila na lang ang nagkatuluyan.” It meant a wishful “what if” my daughter and your son, continued together.

That made me smile. I’ve entered that “what if” world often.

Father and Son

Primitivo Mijares and son, Boyet, during happier days. (Source: Batas Militar/pressreader.com)

“Where’s Boyet,” cried Priscilla, “it’s time to eat.” The Mijares household was complete that evening. There was light banter about Pearl’s joining mass protests. She teased her dad back about his job.

“Baka maging ‘Marcos tuta’ ka, Papa,” (You might become a Marcos lap dog, dad), she smiled, recalling the street chants of a provocateur shouting “Marcos” and the crowd’s one-word response “Tuta,” hollered repeatedly.

She also half-meant it.

--------------------------------------------------------------------

In early 1974, Primitivo Mijares, while on an official mission to the United Nations in New York City, filed for political asylum and started his life in exile. He had recently published his controversial book, The Conjugal Dictatorship of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos. It was a juicy tell-all of the first couple’s lives and loves, interspersed with revelations of the major corruptions.

Imelda was particularly incensed by this expose. Among the many revelations, it documented the infidelities of Ferdinand, confirming stories I heard in private gatherings. It included a detailed account [of Marcos’ tryst] with the American starlet Dovie Beams, and the First Lady’s “hymenal concerns,” quoting the author, Mijares.

I suspected everyone at Newsmen’s Row who mattered, had a copy of the banned book by Primitivo. Teddy Benigno had one. With the permission of his only daughter, Aurora, I was able to read the 500 pages in a few days. I had to be quick; many more friends queued to read it.

The nonfiction print of San Francisco’s Union Square Publications was a rare shining gem. The front cover pictured a reptilian hand with head shots of the Marcos couple. It reached for everything in our land, depicted by its shadow cast over a relief map of Philippine Islands. The book woke the middle class from their stupor.

Primitvo Mijares’ The Conjugal Dictatorship of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos

Aurora then brought out her cassette tape recorder and played a portion of its contents. It was a secret recording by Dovie while in bed with Ferdie, Marcos’ preferred name when he was intimate. They were alone in the summer palace in Baguio City. Ferdie sang to her with all his charm. It sounded like a speech that went sweet.

“Pamulinawen, boto nga timangken. Uray taltalem, saannen nga lumukneng,” was a loose re-interpretation of the classic Ilocano folk song that I wished he sang. It is a metaphor of “Pamulinawen,” a stone-hearted girl who was the subject of a courtship. The ribald version, sung by Marcos, was more fitting for the moment, but Dovie would not get it anyway. The translation to English referred to (his) dick that raged rock hard, and any wankering could not make it soft.

There are advantages to being Teddy Benigno’s daughter, I thought to myself.

My mind was saturated. There was too much to process, considering my life closely orbited around the same center as Pearl’s.

The book of Mr. Mijares dramatically altered their lives.

Primitivo, in a deep change of heart, published his swan song. The Library of Congress Catalog No.76-12246 was given a copy for posterity. He testified before the US House Subcommittee on International Organizations for hearings on the human rights abuses of the Marcos regime. He gained traction as the newest member of the opposition. Mr. Mijares rose to the top of the most-wanted list in the Philippines.

Meanwhile, his family remained in Road 7. The high walls topped with broken glass shards set on mortar were unusual for a home in Project 6. It was like a mini fortress. The sliding patio doors had steel grillwork added. I wondered at the uniformed security guards in blue stationed on the same carport where Pearl and I once rendezvoused. What was there to secure, I curiously asked myself.

Like the “Steak Commandos” of Raul Manglapus in Manhattan, the Harvard-based Ninoy Aquino, and other Filipino opposition groups in exile, Primitivo was harassed by agents loyal to Marcos who had the support of US President Reagan. To make the situation worse, over half of the migrant Filipinos abroad were apathetic to their causes. Primitivo had a lonely and dangerous road ahead.

Primitivo was sought by a scorned Imelda Marcos. By 1975, while on a book tour denouncing the dictatorship, he went into hiding somewhere in the United States.

Back in our neighborhood, I noticed the uneasy quiet of the Mijares home.

---------------------------------------------------------------

In the summer of 1977, our neighborhood was alerted to a missing person -- Boyet. He was last heard leaving for a movie with a mystery friend.

Boyet was targeted by a friendly voice looking for a phone pal. The caller gained Boyet’s confidence with his charming persona. They had so much in common. After a few more calls, the telephone buddies set the time and place for their meeting.

On that fateful day, he told Pearl, “Big sister, I’m going out to watch a movie. I’ll be back for dinner.” Pearl nodded. She had dinner without him.

Outside their home, we made istambay, oblivious of the terror that the Mijares family were experiencing. I was hoping that Pearl would come out and join us.

Breakfast, then lunch, and then another dinner passed; Boyet was a missing person case by the evening.

From an anonymous call the third day, they realized the worst -- he was kidnapped.

Fe Zamora of the Philippine Daily Inquirer later wrote, “The supposed kidnappers had introduced themselves to the Mijares family as the Bangsamoro Army (BMA). At one point, Pilita said, she asked to hear the voice of her brother, but the supposed kidnapper replied: ‘We cannot do that, but we can send you his ear.’”

The reference to the BMA was bogus.

Boyet never returned.

All of a sudden, our Newsmen’s Row was deserted.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Primitivo’s last documented sighting was at the Guam airport. He was on his way back to the Philippines. He hoped to free Boyet by exchanging his life for his dear bunso, his youngest child.

The senior Mijares did not go back home to Newsmen’s Row. Instead, a reunion in a safe house of father and son occurred somewhere in the Philippines. Deprived of their human rights, they were tortured physically and mentally.

Boyet was tougher than the gentle boy who made istambay with us a couple of summers ago. The autopsy report told a tale of horror; “He endured having all his fingernails pulled off by a butcher. He did not break. His body was silenced on the thirteenth stab of an icepick. The next three impalements were unnecessary. Boyet’s body was lifeless.”

(Source: facebook)

“His purified spirit moved me. Boyet was a warrior angel that battled the devil. He won with the loss of his short bittersweet life,” was my belief.

The mangled body of the younger Mijares was found 14 days after walking out of his home for the last time. The older Mijares was presumed dead; his body, nowhere to be found.

Primitivo Mijares’ sacrifice should not be forgotten. His killers, now old and gray, may still walk among us. The murderers should never rest. Imelda used her advanced age and conveniently forgot. The three Marcos offspring, Imelda Junior, Ferdinand Junior, and a complicit Irene have to answer to my generation. Sandro and the dictator’s other grandchildren have to answer to their age group. And so on, until the truth be told.

He told his story and so should we. He bequeathed to his family a book that is relevant to this day. The second edition was published by his heirs during the turmoil of the 1986 elections. A third edition is due this coming presidential election year. The Marcoses and their versions on steroids are brazenly running for the highest offices of our country again.

---------------------------------------------------------------

I always thought of Pearl during those inconceivable times. Amidst all the piercing pain, she found solace in a different love and married him in haste. It was difficult to watch her run to someone else.

Pearl is a now grandmother many times blessed. She currently resides in the United States. Her life is peaceful and she has healed. I see her once every five years, and our meetings are awkward. In her presence, I revert back to being a young lad, unsure of how we can converse.

Some things never change.

Atin Ito News published this piece in three segments: on November 16, 2021; December 1, 2021; and January 1, 2022.

Tom Firme lived his youth in the Philippines, emigrated to Canada in 1993, and is a dual senior citizen of both countries. He and Ingrid Roxas married 38 years ago. They have a unique life together with four beautiful children. Ingrid would complain to her sisters in his presence and half-mean it, with the quip, “Tommy is my youngest child.”

Tom’s first online article was published in 2020 by Atin Ito News of Toronto entitled, Sidcor: A Sunday Morning Farmers Market Series. This story is part of an epic attempt to write a multi-faceted memoir.