Light of the Ancients

/But first, my story. As a kid—and before asthma inhalers were invented—and like most Christian Filipinos, Christmas time was always a time of wonderment and cooler weather; you got to bring out your new sweaters. Manila lowlanders like my family didn’t have to travel to Baguio to feel that cool, crisp, cleaner air. And that was reason enough for us to pile into the car at night, get a break from my asthma attacks, and go around night-time Manila, dressed for the Holidays, of the 1950s.

We’d first head for my Garcia grandparents’ area of Ermita, which took us to the semi-chi-chi commercial area of Mabini. We then crossed the Jones Bridge to Escolta, on to Rizal Avenue and the adjoining Santa Cruz/San Lazaro areas. Modest, middle-class homes had their one or two well-lit parol or lanterns hanging in their windows, and seeing them lit up was reward enough for this asthmatic kid.

Simpler Days: The generic Pilipino star-parol celebrates the “star” that guided the Three Wise Men to the manger in Bethlehem, as a beacon on cold nights.

Then it was on to Quezon City to see the spectacular Christmas display atop Pepsi-Cola’s main building on Balete Drive; and then back home to San Juan. (Makati, Cubao, and Greenhills were just coming into their own.) Those night-time drives through a festive metropolis was balm for a sickly kid and remains one of the fondest memories of my Christmases past.

Along with those nighttime paseo excursions goes the memory of one special lantern I “crafted.”

Remember this?

The most popular brand of cooking grease in the Philippines in the 1950s is inexorably tied in my mind to a “special” do-it-yourself lantern.

As I was into arts and crafts as a kid, one lantern project still stays with me all these years—a “promotional,” mail-order lantern from the Philippine Refining Company (PRC). Their product, Purico Lard & Cooking Oil (yeah, lard and Christmas lanterns, go figure), created this novelty promotion during the holidays. One year, around late November, PRC published in The Manila Times Sunday magazine a how-to-make your own lantern without bamboo sticks, Japanese paper and wire. It was a four-panel affair which just required scissors and paste, and when completed, simulated a wall-sconce or one of those four-sided gas streetlights of European cities early in the 20th century.

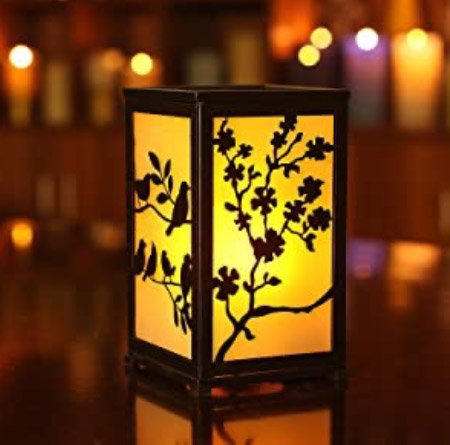

A recreated template of the Purico Do-it-Yourself Christmas lantern with appropriate religious images standing in as faux stained-glass window panes. The original was made of cardboard and translucent paper for the images—all very professionally reproduced. The four panels then folded up to make a square lantern, as in . . . (Author’s photo)

When glued together properly, the finished product looked and glowed like the two images above.

There was a catch, however. You had to send away for the whole kit for a few pesos PLUS a few, if memory serves me right, four, Purico Lard box-tops.

I prevailed on our cook to make sure to buy Purico Lard, and I ambushed those box-tops before anyone else laid their greasy paws on them. When all were collected, I sent away for the kit and template. Because it was almost too easy to assemble and totally different from the generic star parol, I revere the memory of that old Purico lantern.

Of course, today, the Philippines is known during the holidays as one of the most garishly, lavishly decorated parts of the planet. The most elaborate and expensive parols come from Pampanga, but Manila becomes a virtual phantasmagoria of lights and décor. Woe to anyone prone to photosensitive, light-triggered epileptic seizures.

Pampanga's Famous Lantern 2019 | Giant Christmas Lanterns - YouTube

Conceiving X’mas 2021 Décor on the Cheap

Flash forward some 62 years to this season. Having been stuck at home for most of the year, I thought I would go all out with my patio X’mas display. I briefly considered treating myself to the brand new, newfangled, brighter-than-Vegas Filipino parol at the Pinoy supermarkets in the East Bay, but with the $300+ price tag plus sales tax, I decided to dig up my old stuff. Recycling some long dormant Christmas paraphernalia, I found that my older, humbler Pampanga parol, vintage-2016, still worked. That was going to be the centerpiece of my tableau. There were two other lanterns that had been sitting in a box for two decades just crying out to be used. They somehow whispered to me: Bring us to life this year.

Resurrecting the Boracay Parols

I got those two lanterns on a trip to the Boracay in 2000, when the resort was just gaining popularity, the airport was still in Kalibo and a sewer stench still lingered in certain parts of the island. Anyway, aside from that mixed memory, I remember getting two cylindrical Boracay lanterns that didn’t look particularly Christmassy but when lit gave off their own magic.

They had to be squished for transport though, and that’s how they had stayed in a box for 20 years.

Squished. The Boracay lantern on the right – when squished fully, folds flat like the Chinese lantern on the left. They stayed fully squished for two decades. (Photo by Myles Garcia)

Steamed, not broiled. When I decided to revive them, to remove the creases of 20 years, I had to steam-iron the fabric to make them appear like new. Just a little paint came off the fabric. (Photo by Myles Garcia)

Electrical Rigging

And then there was the matter of electrical rigging. I’m not much of an electrician but I know enough about basic electricity to get something going. I found this long aluminum pole in storage (it hosted a banner when our condo complex was having its initial sales), and that was going to be the rig on which the three lanterns would hang.

The pole as I was rigging up the electrical wiring before hanging it up. (Photo by Myles Garcia)

There were two light-bulb sockets and cords salvaged from my hoard of electrical odds-and-ends. Those would light the Boracay lanterns. The thing about the Boracay lanterns were that during the day, they are nothing extraordinary to look at but lit properly at night, they gave off that right Holiday glow.

And I still wanted to keep costs low. With the recycled ingredients in working order, the final stats were: time to assemble the whole mise en scene: under eight hours. Cost? Under $20.00. (The Pampanga parol was estimated at $35 in 2016 when I bought it new, and the two Boracay lanterns were $5 each in 2000.) All in all, not bad, eh?

Et, voila! The finished product on my patio. This is the most ambitious holiday display I’ve attempted in the 16 years I’ve lived in my current address. (Photo by Myles Garcia)

When I threw the switch on, it looked glorious in its simple, humble way.

But for every little triumph, there is always a caveat. When the sun showed up resplendently the next morning, something told me it would make the Boracay lanterns’ colors fade. While they survived the steaming, the morning sun would not be so kind. Luckily, I have an awning to roll down as a protective barrier against sun and rain.

The Ancient Egyptian Connection

Which brings us to the answer to the riddle I posed in the beginning: the concept of “source of light.”

Indeed, the Filipino term parol (for lantern) comes from the Spanish farol, which in turn, comes from the root word faro, which leads us to the pre-Hellenistic Egyptians.

Cleopatra VII, the last of the Ptolomeic Greek rulers, as a female pharaoh, depicted here as the source of light.

In pre-Ptolomeic times (before Alexander the Great’s conquest of Egypt), the ancient Egyptians called their rulers pharaohs (modern spelling but pronounced feyro). When the Greeks entered the picture and established the city of Alexandria, its fabled first lighthouse became known as “faro” (φάρο in Greek). The ancient wonder-of-the-world conflated with the idea of “ruler,” the godhead concept of the leader (the pharaoh) as the source of all life, light, and enlightenment. (The “sun-descended” dynasties were not limited to the ancient Egyptians. Mezo-American kingdoms had theirs and, of course, the longest reigning royal house today, the Japanese royal house, traces its roots to Amaterasu, the sun goddess of their culture.)

The legendary Faro of Alexandria – one of the Seven Ancient Wonders of the World.

Since Alexandria was a major trading port in the Mediterranean, the faro/lighthouse concept was picked up by sailors, including Spaniards, and spread throughout the known civilized world. Thanks to the Roman Empire and Latin, the concept of faro as a lighthouse was maintained consistently by the various Latin cultures. In Latin, lighthouse is phare; in Greek, it is φάρος “faros.” In Spanish and Italian, it became “faro,” and in French, “phare.” But it is the same hierarchical concept of the elevated point being a beacon and source of light.

As Iberian monks and missionaries spread Christianity across the oceans, it was natural for the “faro” concept to cross over eventually to Mexico and its sister Spanish colony, las islas Filipinas. The galleon trade, ‘tis said, brought the parol to the Filipino window, inspired by the Mexican piñatas. The idea of adding lights inside came from the luminarias. But the concept of the “lighthouse” dies hard even in Hispanic parts of the USA—as in this taqueria sign in San Francisco:

Sign of EL FARO (The Lighthouse) Mexican Fast Foods in San Francisco’s Mission District.

The window-hung, electric-lighted Filipino parol as we know it today supposedly first appeared in 1928—during the American Commonwealth era—when one Francisco Estanislao rigged up a star lantern with an electric bulb. That sounds about right, because previously it would not have been advisable to light the paper lanterns with candles. So lighting up lanterns at night could only be possible in the American Era, when electricity and small bulbs came into being, even though the Spaniards are credited with introducing electricity to the islands.

Today, even in the U.S. state of New Mexico, a 393-year-old controversy still rages over what the “candle lights in sand-filled paper bags” are called. Supposedly south of La Bajada Hill, they’re called luminarias, but north of that town, they’re called farolitos. So there you go.

New Mexican luminarias (or farolitos?)

So, as in the time of ancient Egyptians, our Christmas parol functions as a beacon of light (our “lighthouse”) in the dark Christmas nights. In any case, a safe and Merry Christmas to everyone.

Sources:

Luminarias or Farolitos? (newmexico.org)

Uncharted Philippines | Examining the Origin of the Paról, the Filipino Christmas Star

Myles A. Garcia is a Correspondent and regular contributor to www.positivelyfilipino.com. He has written three books:

· Secrets of the Olympic Ceremonies (latest edition, 2021);

· Thirty Years Later . . . Catching Up with the Marcos-Era Crimes (© 2016); and

· Of Adobo, Apple Pie, and Schnitzel With Noodles (© 2018)—all available in paperback from amazon.com (Australia, USA, Canada, UK and Europe).

Myles is also a member of the International Society of Olympic Historians, contributing to the ISOH Journal, and pursuing dramatic writing lately. For any enquiries: razor323@gmail.com

More articles from Myles A. Garcia