30 Years Ago: Coup d'etat and People Power

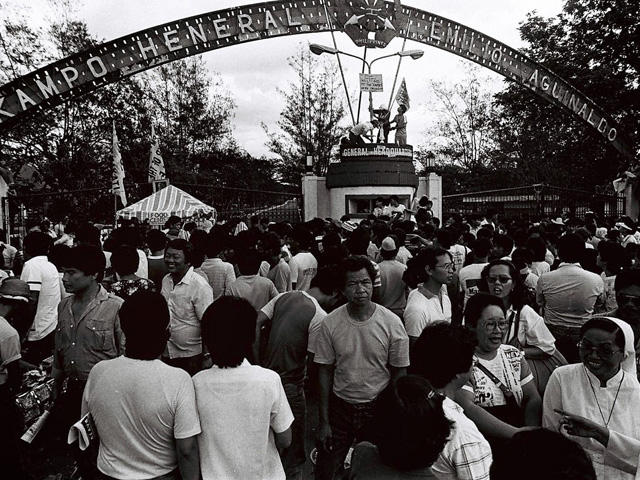

/Pro-Aquino supporters rally around rebel soldiers who broke away from the Marcos government and based themselves in Camp Aguinaldo and Camp Crame along EDSA (Photo by Joe Galvez/GMA News)

Thousands of “I was there” stories have been told and many more continue to be told. On this 30th anniversary of the historical event, we leave it to the other publications to recall those tense but ultimately glorious moments when the Filipino people made its will known, loudly, unconventionally and peacefully.

What has been downplayed in the historical accounts, however, is the true story of the military operation planned by the leaders of the Reform the Armed Forces Movement (RAM), the military rebel group, and the counter-operation or defensive action that would have been effected by the Presidential Security Command (PSC) that was defending Malacañang Palace and the presidential family.

How It Started

The Armed Forces of the Philippines circa 1986 was no longer the cohesive, monolithic military organization that Marcos relied on to implement martial law in 1972. While he still had the loyalty of the top generals he appointed, younger officers, many of them graduates of the Philippine Military Academy (PMA) from 1971 onwards, were no longer bound to the strident, single-minded anti-Communist, pro-American theology of their senior officers. Since they were the ones sent to the field to fight, their exposure to the stark inequalities of Philippine society opened their eyes to the realities of the organization they belong to. And those realities included graft and corruption, favoritism, unprofessionalism, incompetence, among others.

When the Aquino assassination happened – an obvious military operation even if officially unsanctioned – the die was cast for many of these young officers. They started organizing themselves – secretly, still outwardly functioning within the much vaunted chain of command – into the Reform the Armed Forces Movement (RAM), a group that proclaimed itself the champion of making changes in the military in order to make it stronger. As it would be revealed later, there were two RAM operating groups: the first was handled by the Philippine Constabulary (PC) group that held informal discussions with junior officers and soldiers and documented ”the various exploitable issues within the military such as favoritism, extension of service, graft and corruption, etc.” This segment’s objective, according to Col. Alex Flores, head of the Education Committee of RAM’s Steering Committee, was “to add sophistication to the politically aware but partisan-veering military mind.”

The other RAM group was that from the Ministry of National Defense (MND), led by Colonels Gregorio Honasan and Red Kapunan who were planning what they euphemistically called a “tactical defensive action” against the Marcos regime.

The RAM group led by Col. Gregorio "Gringo" Honasan (Source: the Presidential Museum and Library)

It was this operation that provided the trigger that led to the unscripted phenomenon that is now enshrined as the EDSA People Power Revolution of 1986.

The Plot

What it was in unadorned nomenclature was a coup d’etat. Seizure of political power. The plan was to set up a junta or governing committee to be composed of civilian and former military officials to take over the reins of government. According to one account, the junta would have been composed of five: Enrile, Rafael Ileto, Cardinal Sin, Cory Aquino and then United Nations Deputy Secretary General (and former Executive Secretary of Marcos) Rafael Salas. Another version said the committee would be composed of sectoral representatives, presumably including the more decent elements of the KBL. The turnover of authority to Cory Aquino and Laurel was only the third option, as Enrile would later confirm.

The junta would hold power for a year, as the RAM coup plotters planned. It would call for a constitutional convention and presidential and local elections within that period. No one among the proposed members, except Enrile, knew about their designated post-coup roles.

Planning for the coup was an elaborate operation that involved months of top secret meetings with active military officials, opposition leaders (they did not talk directly to Cory, but with her brother, Peping Cojuangco), the media, US government officials, some “friendly” members of Marcos’ cabinet and other government officials. RAM even set up an elaborate road tour called Kamalayan that campaigned to ensure clean and honest elections, but was really a cover for visiting various military camps and recruiting supporters for the coup.

Cory Aquino, campaigning during the snap elections of February, 1986 (Source: AP)

Zero hour for the military action was set at dawn on February 23. As the presidential family would be sleeping, and their close-in security believed to be relaxing at the witching hour, the siege of Malacañang would be staged simultaneously from four points – from the Pasig river, from Malacañang Park (headquarters of the Presidential Security Command or PSC), through the Palace gymnasium and the palace gate at J.P. Laurel St. It was a highly ambitious entry plan that involved several companies from the Scout Rangers and the Army, and some Palace insiders strategically placed and with very specific if limited tasks, to enable the invading group to enter the private quarters of the Marcoses. The intent was to “convince” the civilian and military leadership to step down, after which the reformists would declare a revolutionary government and immediately convene a military tribunal to try some top military officials for criminal acts against the Filipino people.

The Malacañang siege would have taken place simultaneously with less spectacular attacks in Fort Bonifacio and Villamor Air Base to neutralize the major services’ high command and bring Marcos’ generals to trial. Other reformist officers stationed in the provinces would have operationalized their camps’ takeover to grab the leadership from abusive commanders and also put them on trial.

The plan was exciting and ambitious, its goals lofty. The problem was it did not take into account the possibility that Marcos’ loyal troops of the Presidential Security Group (PSG) would be able to uncover the plot and take preemptive actions accordingly. And that was exactly what happened.

Coup d’etat Filipino Style

For a coup to be successful, there has to be utmost secrecy and lightning-fast action. The fewer people who know of the plot, the greater the chances of achieving its goal. The element of surprise is also crucial; the action should be done before loyal troops are able to respond.

Looking back now when more details have been admitted and confirmed, the RAM plot failed on both counts. While the plotters took pains to implement on a need-to-know basis the critical elements of the plan (only Honasan and Kapunan, and possibly Enrile because he was the boss and had to be briefed, knew of the overall picture; the others were told only of what they were specifically tasked to do), it involved too many troop movements, both military and civilian. Some junior officers who were assigned their specific duties then would say now that Gringo (Honasan’s nickname) and his troops were practically taunting the Ver troops by openly doing target shooting and military exercises for months before D-day, thus triggering suspicions that they were up to something.

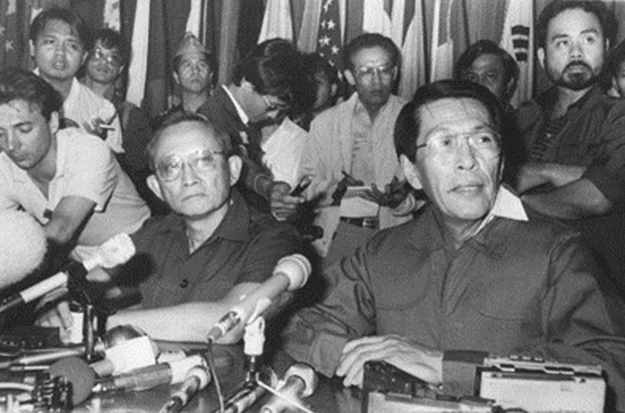

On February 23, Minister Juan Ponce Enrile, RAM leader Col. Honasan (right foreground), and his men left Camp Aguinaldo to join General Fidel Ramos in Camp Crame. (Photo by Tom Haley)

Then there was the Palace siege plan, again involving major troop movements and a slow approach. How fast can you navigate the Pasig River after all before the loyalist troops would be alerted, even in the off chance that there were no prior information leaks?

And there were information leaks, some of them deliberate, others unexpected. There were moles on both the Palace side and the RAM side reporting on unusual activities that would indicate an adjustment of plans. The PSC suspected some possible illegal action by the reformists as early as December 1985 while the snap election campaign was going on. The coup plotters were getting information that security at the Palace was beefed up so intensely that it was already like a fortress.

A week before zero hour, with camps all on red alert due to the uncertainties of election results, the plotters deliberately leaked details of a plot to kidnap the president and the first lady, but it was a hoax intended to see how the Marcos bodyguards would react.

“All Systems Go”

The decision to strike on February 23 was brought about by a number of factors. As the RAM correctly assessed, the outraged population was raring for a fight and Cory Aquino’s civil disobedience campaign had caught fire. Enrile and other sympathetic officials would resign, adding drama to the coup plotters’ move. A retired colonel in Enrile’s office who dabbled in astrology forecasted a favorable alignment of the moon and the planets on that date.

It was “all systems go.” The families of the lead players had been taken to safer places and Kapunan had arranged three months’ worth of salaries for his men. For two weeks prior, lesser known reformist groups had been doing daily reconnaissance of the palace grounds and the park where the PSC was headquartered.

But on Thursday, February 20, the RAM tactical group began to sense that something was wrong. Tanks were moved from the park across the Pasig River to the grounds of the presidential palace. One marine battalion from Fort Bonifacio was also transferred to the compound. RAM operatives were also receiving cryptic messages from friends with access to Malacañang.

At around 4 am of D-day, General Artemio Tadiar, commander of the Philippine Marines, woke up to go to the bathroom in his single-story military quarters in Fort Bonifacio. While there, he heard some shuffling in the grass outside and whispers. Peeking out the window, he saw heavily armed soldiers in combat uniform surrounding the house, guns pointed. He immediately called the Military Police, in charge of base security, to report the suspicious activity. That was how 19 persons, 16 of which were civilians, and led by a RAM member, were arrested. The arrest threw the coup plot in disarray because some of those arrested were part of Enrile’s security force detailed with finance minister Roberto Ongpin.

When a RAM mole in PSC reported that booby traps were being laid out in the palace grounds, Honasan and Kapunan decided to freeze implementation of the coup. Along with Enrile’s aide, Capt. Noe Wong, they went to Enrile at the latter’s home in Dasmarinas Village to report that the plot had been compromised. They suggested that the defense minister fly to his home province of Cagayan until things cooled down and they could regroup. The plotters, meanwhile, would go into hiding and wait for an opportune time to carry through their plan. It was then that Enrile made the momentous decision to hold out at the MND as a “symbolic act,” if nothing else, before the fight to the death.

Though that “symbolic act” was later romanticized as heroism, it was not aimed at saving the nation but rather to save their skins from a vindictive strongman and his henchmen.

Holding out at the MND building, the RAM men knew, was not such a good idea. They did not control Camp Aguinaldo and the area itself could easily be assaulted by tanks. They also realized that the odds were against them, but if they were to be annihilated, the whole world would be witness to the slaughter and would direct their outrage at Marcos. With their deaths, they would have achieved what they had started out to do in the first place. It was a time for heroics and they were, undoubtedly, the martyrs of the hour.

Notwithstanding their acceptance of the inevitable, they also took steps to increase their chances of survival. Kapunan and another PMA classmate, Col. Rey Rivera, took care of defensive positions in case of an attack on MND, which by then was already filled with hundreds of journalists and sympathizers. Outside the gates, a large crowd had already heeded the call of Butz Aquino and Cardinal Sin, to gather and protect the soldiers holed up inside the building. Kapunan, who was in charge of diversionary tactics, farmed out small mobile troops with anti-tank and anti-aircraft weapons in strategic places around the camp. One hundred twenty five men, including young RAM officers, were deployed to Fairview, near Montalban, to await instructions. There were the soldiers who would eventually undertake the operations against Channels 4 and 9.

In Camp Crame, headquarters of the Philippine Constabulary, Ramos’ home base, the situation was worse. Col. Flores confirms that between his staff and the Special Action Force (SAF) of Capt. Rosendo Ferrer, “we had no more than 80 men with meager armaments, ammunition and explosive resources.” Camp Crame had become a ghost town after Enrile and Ramos made their withdrawal announcement, with soldiers and their families leaving the camp. Unlike in Aguinaldo which already had a sizeable crowd surrounding its gates, Crame would have been a very easy target for attack.

General Fidel V. Ramos and Defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile (Source: Inquirer.net)

It turned out that the Malacañang forces had no plans to attack that night (or any other time during the 77 hours for that matter). When they had arrested Capt. Ricardo Morales, Lt. Col. Jake Malajacan and Major Saulito Aromin – all RAM and part of the coup operation – they correctly surmised that the coup plot was foiled. The three were presented on TV by Marcos later that night of February 22 and Morales read a prepared statement that identified the coup leaders and outlined the plotters’ plan to enter Malacañang. Marcos called the plot an assassination attempt on him and the first lady, dismissed the plotters’ manpower as puny, and ended his press conference by calling on the plotters to surrender to avoid bloodshed. His orders to his men was to hold back, not to attack Camp Aguinaldo because he was going to talk “Johnny and Eddie” out of their “foolishness.”

(To get the complete story of the EDSA People Power Revolution of 1986, read also Criselda Yabes’ comprehensive article on what was happening on the Malacañang side in "Last Waltz at the Palace: The Untold Story of People Power" in Rogue magazine: http://rogue.ph/last-waltz-at-the-palace-the-untold-story-of-people-power/)

Though the actual coup had been stopped in its tracks, however, no one expected the massive civilian show of force that took over the historical moment, changed the dynamics of the conflict and stayed on in EDSA despite the danger, the threats of martial law and violent dispersal, the psywar (between the two opposing military forces), and the many serious uncertainties that the swiftly changing political situation triggered.

The entire world witnessed the astounding political theater and was stunned. People power was the wild card in this life-and-death drama for the ages and nothing like it had happened before.

A Third Force

Beyond the military maneuverings and the civilian response (already well documented by photographs, videos and first-person accounts) however, was the very real issue of succession. Like everyone else, the political opposition was unprepared for these unprecedented developments and did not anticipate that the military rebels would checkmate the dictatorship’s forces in one fell swoop.

On the second day of the rebellion, Cory Aquino called Cardinal Sin to update him on the situation. “We have a problem,” she said, “there is a third force.” That “third force” was the politicized military sector that was now pushing for its leading role in determining the structure of the successor government.

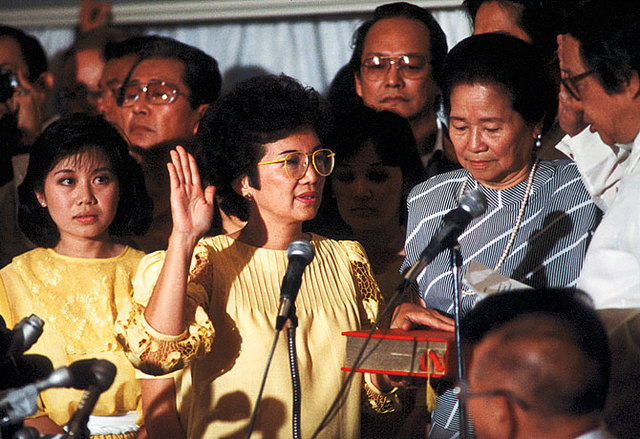

When Enrile suggested that she ride a helicopter to Camp Crame and take her oath of office as the new president there, Cory strongly refused. Camp Crame, Enrile argued, was the most secure and politically symbolic site because it had already become the cradle of the civilian-military revolt which had then already swelled into spontaneous people power. The crowd in EDSA would be ecstatic to acclaim their new president and commander-in-chief.

Cory saw through the Enrile game. As presidential spokesman Rene Saguisag would later recount, “She decided for herself even before anyone could tell her of Minister Enrile’s suggestion.” Cory Aquino had consistently maintained that the people elected her and that Marcos had robbed the Filipino people of their clear mandate. A Camp Crame oath-taking would thus render her popular victory into a hostage presidency – installed not by people’s votes but by a rebellious military faction.

Her instincts were correct as proven in the succeeding years as this military faction, furious about not getting its due in ousting the Marcos dictatorship, would stage several failed coups against her administration.

Cory took her oath of office at Club Filipino with Enrile and Ramos in attendance only as part of the guest list. The rest is history.

Cory Aquino, taking her oath of office at Club Filipino (Source: Official Gazette)

When Marcos, his family and his loyal supporters boarded the US helicopters to go to Clark Air Base and eventually exile, pandemonium broke out nationwide as church bells peeled, firecrackers exploded, and millions of Filipinos spilled out in the streets, crying, singing, embracing each other in solidarity. It was as Cory Aquino predicted it to be: “When I become president, there will be dancing in the streets.”

Excerpts of this article came from the chapter I wrote entitled “The Fall of the Regime,” in the book Dictatorship and Revolution: Roots of People Power (Conspectus Foundation Inc., 1988).

The following contributed new information to this article: Criselda Yabes, Alex Flores, Vic Batac, Roilo Golez, Rene Saguisag and Irwin Ver.