12 Mind-blowing Facts About Metro Manila

/But Manila is still the country’s capital, and celebrating its foundation day is more about looking forward to the future and less about thinking how we fell behind in terms of economic progress.

In order to move forward, however, we also need to look back to our past. After all, there are so many stories and facts about Manila that those who live in the city aren’t even aware of.

Here are some of the most fascinating facts about Manila you probably don’t know:

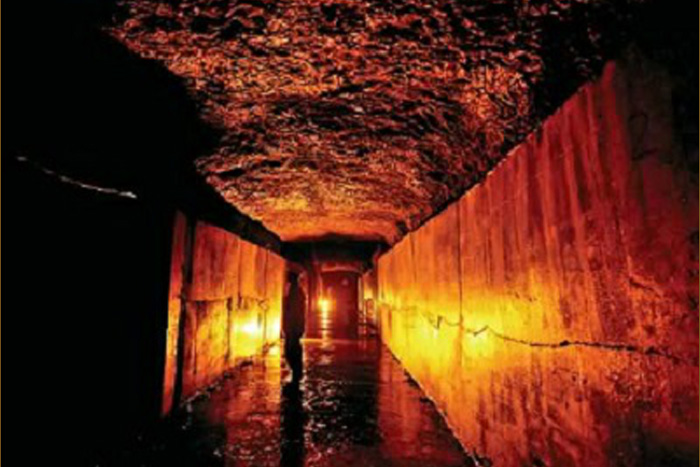

1. Secret underground tunnels

Secret tunnel? (Photo by Richard A. Reyes)

Manila’s busiest commercial districts are clear reminders of the city’s modernity. Anyone who frequents these places would always expect to see towering skyscrapers, condominiums and posh boutiques. But underground tunnels older than WWII? Highly unlikely.

To the surprise of many, both Makati City and Bonifacio Global City in Taguig actually have secret passageways hidden underneath them.

In January 2011, the crew of Manila Water discovered a tunnel during one of its digging operations at the Epifanio delos Santos Avenue (EDSA)-Guadalupe area. Although few information has been revealed about the said man-made tunnel, it is reportedly located 3.5 meters below the street level and wide enough to fit several dump trucks.

The Fort Bonifacio Tunnel, on the other hand, has a more interesting history. Located near Megaworld, the tunnel is about 2.24 km long and four meters wide. It is equipped with 32 built-in chambers, a six-meter-deep well, and two exits leading to Barangay East Rembo and Barangay Pembo in Makati City.

There are four entrances to the tunnel that currently exist: The first is across C5 (near Market! Market!) while the other one is found on East Rembo. The third entrance is at Amapola Street, although it has been closed to give way to the construction of a new house. The fourth entrance is open and found on Morning Glory Street.

Although some say that the tunnel was built under the order of General Douglas MacArthur in 1942, historical accounts show that it was constructed much earlier. Retired Brig. Gen. Restituto Aguilar, also the former director of the Philippine Army Museum, said that the construction of the tunnel started in the early 1900s through the efforts of the Igorot miners from the Cordillera.

The tunnel was initially used as an “underground highway” which helped transport food, medicines, and other military supplies to Fort McKinley (now Fort Bonifacio). It was then expanded in 1936 to serve as Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s headquarters and storage room for military supplies.

When the WWII broke out, the Japanese destroyed Fort McKinley and renamed it “Sakura Heiei.” The tunnel, on the other hand, served as temporary shelter of high-ranking Japanese military officials, including Gen. Tomoyuki Yamashita.

After the war, the tunnel was turned over to the Philippine government. Fort McKinley was renamed Fort Andres Bonifacio and became a Central Business District in 1994. The underground tunnel was eventually closed in 1995, and since then most Filipinos have forgotten that such historical treasure exists.

In 2012, the Bases Conversion and Development Authority (BCDA) disclosed plans of developing the Fort Bonifacio Tunnel into a historic site to help protect its legacy.

2. The height of Quezon Memorial Shrine’s three vertical pylons was based on President Quezon’s age when he died.

There is a reason for the height of the Quezon Memorial in Quezon City (Photo by Jodel Cuasay via Flickr)

The Quezon Memorial Circle houses the museum, shrine and the remains of former President Manuel L. Quezon as well as First Lady Aurora Quezon.

Modeled after Napoleon Bonaparte’s catafalque in Les Invalides, France, the Quezon Memorial Shrine was the brainchild of Federico Ilustre, an architect who bested other finalists to create the monument’s final design.

The monument has three vertical pylons symbolizing Luzon, Visayas and Mindanao. They measure 66 meters in height, based on President Quezon’s age when he died on August 1, 1944. There are also three angels holding sampaguita wreaths on top, which were created by Italian sculptor Monti.

Construction of the Quezon Memorial Shrine started in the 1950s but was only completed in 1978 due to several factors like lack of funds and the difficulty of importing Carrara marble, which came in blocks and carved on site.

On August 19, 1979, President Quezon’s remains were transferred from Manila North Cemetery to the Quezon Memorial Circle. In the same year, President Ferdinand Marcos declared the site a National Shrine.

3. General Douglas MacArthur served as Manila Hotel’s “General Manager.”

Gen. Douglas MacArthur and the MacArthur Suite at Manila Hotel (Source: filipiknow.net)

Established on July 4, 1912, the Manila Hotel witnessed several landmark events and became home to some of the most important people in Philippine history–including Gen. Douglas MacArthur.

In 1935, MacArthur was commissioned by President Quezon to help build the Philippine army and serve as military advisor of the Commonwealth. From 1935 to 1941, MacArthur stayed in the Manila Hotel together with his wife Jean and son Arthur.

Before they arrived in the Philippines, President Quezon hired architect Andres Luna de San Pedro, son of famous painter Juan Luna, to build a seven-room penthouse in the hotel. MacArthur lived a life of luxury and fully enjoyed his favorite food there: native lapu-lapu wrapped in banana leaves.

The cost of MacArthur’s suite eventually drained the hotel’s budget, and Quezon, upon receiving the bill, called Mayor Jorge Vargas to settle the problem. To handle the cost, it was decided to give MacArthur the honorary title of “General Manager.” Although he was considered a figurehead, MacArthur ignored his status and still took charge of hotel management.

4. Harrison Plaza and other areas in Manila used to be cemeteries.

Monument of a cemetery located at the south west of Fort San Antonio Abad. The area is where the present-day Harrison Plaza now stands. (Photo by John Tewell via Flickr)

As a result of modernization, some sacred burial grounds had to be wiped out to be replaced by commercial buildings. Such is the case with an old cemetery located southwest of an area once known as Fort San Antonio Abad in Malate, Manila. The area is now occupied by the Harrison Plaza, also known as the country’s first modern mall.

But Harrison Plaza is not the only one that lies above former burial grounds. Another area in Malate, the Remedios Circle, was actually one of Manila’s earliest cemeteries. However, it closed down after WWII, and all the remains were transferred to the South Cemetery. This happened after the Catholic Church agreed to surrender the cemetery to the government in exchange of a road leading to a new church across the Manila Zoo.

Another former cemetery is the Espiritu Santo Parish Church in Sta. Cruz, Manila. It is known as the first church in the country dedicated to the Holy Spirit. It used to be a simple place of worship in the middle of Sta. Cruz Cemetery. The area around the cemetery was eventually converted into the Parish of Espiritu Santo by the La Liga del Espiritu Santo led by Florentino Torres, Supreme Court’s first associate justice. The small chapel within the cemetery was built into a bigger church in 1926.

5. Tomas Claudio Boulevard in Malate was named after the ONLY Filipino casualty of the First World War.

Tomas Claudio (Source: Tomas Claudio Memorial College)

Born on May 7, 1892, Tomas Mateo Claudio was originally from Morong, Rizal. He was hired by the Bureau of Prisons as a guard but was fired shortly after he was caught sleeping during working hours. He then moved to the US where he got a job at a sugar plantation in Hawaii, and later as a salmon canner in Alaska. Eventually, he got a chance to study commerce at a college in Nevada. After graduation, Claudio worked at a local Post Office as a clerk.

Claudio, already a Filipino American, then decided to enlist in the U.S. Army. He was one of the members of the American Expeditionary Force to France sent to fight against the Germans during World War I. Unfortunately, he died in a battle on June 29, 1918, making him the first Fil-Am war hero and also the only Filipino casualty of World War I.

To honor his bravery, the Private Tomas Claudio Post 1063 Veterans of Foreign Wars of the U.S. was established in 1923 by a group of Fil-Am veterans of WWI. A college, a street, and a bridge in the Philippines were also named after him to honor his contributions.

6. Felix R. Hidalgo Street in Quiapo was once considered “the most beautiful street in Manila.”

San Sebastian Street (Felix R. Hidalgo Street today) looking northeast towards San Sebastian Church in 1899. (Photo by John Tewell via Flickr)

Named after the famous 19th century Filipino painter, Felix R. Hidalgo Street in Quiapo, Manila, is known for connecting two churches: the San Sebastian Basilica and the Basilica of Quiapo. Although it is now filled with illegal settlers, dilapidated houses and commercial establishments, R. Hidalgo Street was not like this centuries ago. In fact, it was called “the most beautiful street in Manila” in 1817, mainly because of the grand mansions that once stood in the area.

Formerly known as San Sebastian Street, R. Hidalgo Street was once home to upper and middle class families during the Spanish era. According to Dr. Fernando Nakpil Zialcita, an anthropology professor who studied Manila’s historical streets, the thoroughfare was a preferred location because it was near schools, churches, the Malacañang and several recreational centers on Rizal Avenue. Unfortunately, the once celebrated street started to decline during the 1960s.

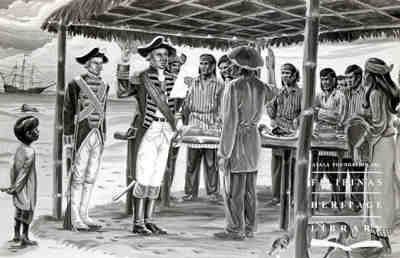

7. The British invaded and ruled Manila for two years (1762-1764).

The British take over Manila. (Source: Filipinas Heritage Library)

The two-year British occupation of Manila was one of the consequences of the Seven Years War (1756-1763), which pitted British against France and its allies—including Spain.

Although the war was mainly fought in Europe, it also reached the colonies of the involved countries. At the time, the British had already established the East India Company, which saw the conflict as an opportunity to invade the Philippines. The British army arrived in the Philippine Archipelago on September 23, 1762 with 13 ships and more than 6, 000 troops led by Brigadier General William Draper and Rear-Admiral Samuel Cornish.

The news about the impending invasion reached Archbishop Miguel Rojo, then acting Governor-General, the day before it took place. As a result, Manila was put in a State of Defense. However, the British fleet successfully arrived in Manila Bay and plans of a widespread attack on Manila were made afterwards.

The British army eventually captured the fort of Polverista, but the subsequent killing of their soldiers by the Spaniards forced Brig. Gen. Draper to send a threatening letter to Archbishop Rojo. The latter responded with a letter of apology along with a request to release Antonio Tagle, the Archbishop’s nephew, who had been captured. The British agreed to free Tagle, but he was killed along with British Lieutenant Fryar upon arrival.

The incident infuriated the British even more, and they started to destroy Intramuros the following day. The bombardment continued until 6th of October when the Spanish finally surrendered the city to the invaders.

The British occupation would last for two years, but their power would not extend beyond Manila and Cavite—thanks to Governor Simon de Anda y Salazar who moved to Bacolor, Pampanga, and continued to fight for more than a year and a half. The British officially left the Philippines after the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1764.

8. In 16th century Manila, the Muslims were the ruling class while the Tagalogs were considered inferior.

A tagalog royal and his wife in the 16th century (Source: filipiknow.net and Boxer Codex)

During the 16th century, Manila, known then as Kota Salurong (or Seludong), was under Muslim control. It all started when Sultan Bulkeaiah (Nakhoda Ragam) of Brunei conquered the Kingdom of Tondo and established Kota Salurong as an outpost of his sultanate. Soon, the Muslims became the ruling class and fully controlled the wealth, trade and the seat of government in the old Manila.

The Tagalogs, on the other hand, were considered second-class citizens who wore long hair, carried weapons such as daggers and rarely traveled by land. Under Muslim rule, the Tagalogs learned to adopt the culture of their conquerors. They started to use Muslim names, wore turbans, read the Quran and even refused to eat pork.

9. Dwight D. Eisenhower almost became Quezon City’s first chief of police.

Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower (Source: filipiknow.net and wikipedia.org)

In October 1939, President Manuel L. Quezon discussed his plans of establishing a new city with General Douglas MacArthur, his military adviser at the time. Quezon valued the latter’s opinions due to his “keen, analytical mind.” After he decided that he would take over the mayoralty, Quezon asked MacArthur if he knew someone who could be an effective chief of police for the new city. MacArthur scanned the room and pointed to one of his assistants. The young man, as it turned out, was then Lieutenant Colonel Dwight D. Eisenhower, a future U.S. president.

Of course, Eisenhower was qualified for the position as he had some police training in the States. But when Quezon was about to appoint him, the young Eisenhower refused, explaining that he made a promise to his wife to go back home after his tour of duty.

10. Escolta boasts many firsts in the Philippines.

Escolta Street in the mid-1950s (Photo by Lou Gopal of Manila Nostalgia)

You probably already know that Clarke’s Ice Cream Parlor on the west side of present-day Jones Bridge was the first ice cream store in the country. This soda fountain and restaurant was brought to the country by an American entrepreneur named M.A. “Met” Clarke.

But this ice cream parlor was just one of Escolta’s trailblazers.

There’s also Salon de Pertierra, which opened in 1896 and became the first movie house in the country. It was designed to show Pertierra’s first movie in Manila, which was finally shown in January 1897. The first four movies were silent French films with subtitles and accompanied by an orchestra.

Escolta, known by pre-war Filipinos as the shopping strip for the upper- and middle-classes, was also home to the country’s first electric cable car (Tranvia), the first American-style department store (Beck’s) and first elevator (at the Burke Building).

11. Manila Day (June 24) marks the foundation of Intramuros, not the Manila we know today.

The reconstructed gate at Fort Santiago in Intramuros, Manila (Source: filipiknow.net and wikipedia.org)

Unknown to many, Manila Day, which is held every 24th of June, commemorates the foundation of Spanish Manila.

Spanish Manila, however, was limited to the areas within the walls, hence Intramuros. In other words, Manila Day celebrates the foundation of Intramuros, not the Metro Manila we know today, which were actually suburbs or arrabales outside the walls.

12. Manila City Hall is shaped like a coffin with a cross on it when viewed from the top.

Views of Manila City Hall (Source: filipiknow.net)

Scary as it may sound, the Manila City Hall actually looks like a coffin when viewed from the top, as shown by several aerial shots proliferating on the Internet.

Manila was one of the most bombed cities during WWII, and the Manila City Hall often scares its employees with strange noises and footsteps that often occur at midnight.

First published in http://www.filipiknow.net/manila-history-and-trivia/

Luisito E. Batongbakal, Jr. is the founder, author and editor-in-chief of FilipiKnow.net. He has a fetish for local trivia, unsolved mysteries, and all things creepy.

Follow him at:

Twitter: https://twitter.com/PinoyLister

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/cryptic0614

Pinterest: http://www.pinterest.com/filipiknow/

Website: http://www.filipiknow.net/