Winter in the Imperial Valley: Lettuce Season, 1965

/Journal of a ‘60s California Farm Worker, Part 1

(Image courtesy of Alex Fabros, Jr. This image has been digitally enhanced using AI.)

(These five essays are pieces of my life, each one capturing a chapter in my journey from a young migrant laborer to a United States Marine. They begin in the Imperial Valley, where I worked the lettuce fields alongside other Filipino farmworkers, learning the rhythms of planting, cutting, and packing under the desert sun. From there, the story moves to Gonzales, where the asparagus harvest tested both body and will, and where the camaraderie of the bunkhouse softened the hardships of the work.

In Coachella, the grape harvest unfolded alongside weekends in Los Angeles — a mix of backbreaking field labor and fleeting moments of youth, music, and romance. Delano follows, where I arrived in September 1965 during a turning point in farm labor history, as Filipino and Mexican workers stood together in strikes that would reshape the agricultural industry.

The final essay brings me into the United States Marine Corps, where the discipline, endurance, and teamwork I had learned in the fields became the foundation for my military service.

Together, these essays are not just my personal story, but also a record of a generation of Filipino Americans whose labor and lives were deeply woven into the history of California and the nation.)

Rice was always first, big battered aluminum calderos of them set over roaring flames. You’d hear the lid rattle, smell the steam, and know the heart of the meal was ready. If the rice was short, we stretched it with day-old French bread bought in Holtville or El Centro.

Pinakbet (mixed vegetable stew) was a mainstay, though in California, it wore a different coat. The manongs used what the Imperial Valley fields could give—bitter melon from a garden behind the bunkhouse, eggplant, okra, tomatoes, and Mexican calabacita squash. We cooked it down with bagoong from a bottle, or mashed canned anchovies if that’s what we had. Sometimes the whole pot would melt into a salty, savory stew that clung to the rice.

There was always soup—dinengdeng, light but sharp with bagoong in the broth. We’d drop in mustard greens or sweet potato tops, and, if the company truck had brought fish from San Diego, a grilled mackerel to flavor it. Bagnet—deep-fried salt pork—was our treasure. We boiled the pork belly with garlic and salt, then fried it in a blackened wok until the skin blistered. The pieces cracked between your teeth, chased by a splash of sukang Iloko or cane vinegar with chili.

On the table sat sliced tomatoes and onions, salted just enough to cut through the richness. Beside them were jars of bagoong—thick, pungent, salty—and coffee mugs filled with chili vinegar. Every man knew where his spoon and cup were.

Dessert was rare, but if we had bananas from the Mexican market, they’d be fried until golden. On Sundays, pan de sal would arrive from Los Angeles or San Diego, split open, spread with margarine, and dusted with sugar. Coffee was always on, strong enough to jolt you awake even after a long day in the rows.

We ate family-style, elbows on the table, talking in Ilocano, Tagalog, English, and sometimes Spanish. The meals were simple, salty, and filling—the kind that warmed you from the inside out after hours bent over in the cold lettuce fields. They were never just food; they were the taste of home carried thousands of miles, rebuilt from whatever we could find in that desert valley.

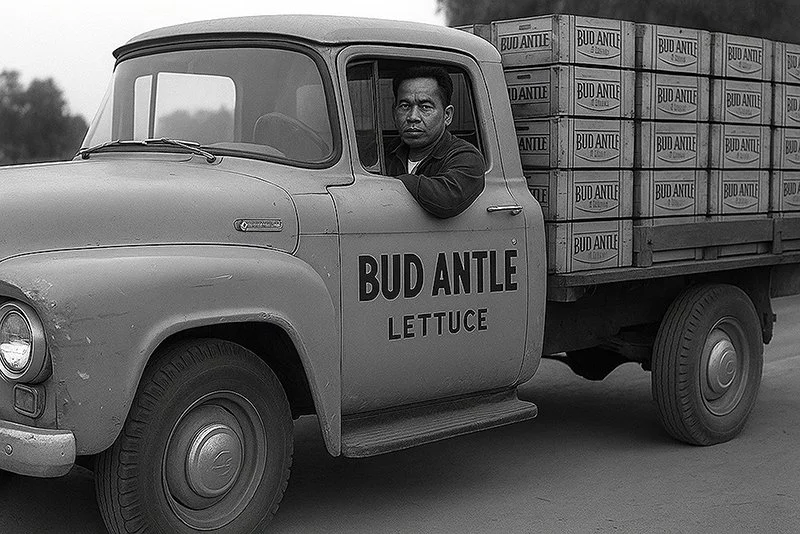

The End of the Bracero Era

(Image courtesy of Alex Fabros, Jr. This image has been digitally enhanced using AI.)

Only a year earlier, the Bracero Program had ended. From 1942 to 1964, it had brought hundreds of thousands of Mexican men north under temporary contracts to harvest crops. When it shut down, growers scrambled to fill the gap, leaning harder on crews of Mexican Americans, newly arrived Mexican immigrants, and the ever-resilient Filipino networks that had been in place for decades.

Our camp reflected that shift. The next bunkhouse over was mostly Mexican, some of them former braceros who had decided to stay. We shared the same fields and mess hall, though after work most men kept to their own groups.

Evenings in the Camp, Weekends in Town

After supper, the camp settled into its nighttime rhythm. Some men wrote letters home, others listened to the radio. Our bunkhouse had an RCA AM-only radio and a 13-inch black and white TV with rabbit ears that could pull in a few stations from Yuma and El Centro if the weather was right. At night, we could tune in to Wolfman Jack on XERB 1090 out of Rosarito Beach, his gravelly voice and howl cutting through the static, spinning rock ’n’ roll and R&B across the desert.

Most nights, there was poker. At first, I sat and watched. The manongs were casual with their coins but serious about the game. I noticed how a man leaned back when he had nothing, forward when his hand was good. I paid attention to how they traded cards — two meant chasing something, one meant they probably had it.

I started playing, losing more than I won, but studying every move. Slowly, I got better. I learned to read the tells, to keep my face still, to know when to push and when to fold. Sometimes I walked away a few dollars ahead, enough for groceries or a Saturday bus trip into Holtville.

Most nights at the bunkhouse, there was poker. (Image courtesy of Alex Fabros, Jr. This image has been digitally enhanced using AI.)

Holtville had a small Filipino community, but it wasn’t alone. Across the Imperial Valley, in towns like Calexico, El Centro, Brawley, and Westmorland, clusters of Filipinos lived in rented houses, shared apartments, and small labor camps on the outskirts of town. These communities had grown out of the 1920s and 1930s manong migration and stayed alive through the decades by maintaining ties across the valley.

On Saturday nights, the social calendar belonged to the Filipino halls and lodges. Holtville might host a dance one week, Calexico the next, then Brawley or El Centro. Each community had its own hall or rented space, decorated with crepe paper streamers, and a small bandstand. The music ranged from kundiman ballads to the latest American pop hits, and the dance floor was open to all — Filipinos, Mexican Filipinos, white Filipinos, and friends from surrounding towns.

In Holtville, there was a weekly Saturday night dance. (Image courtesy of Alex Fabros, Jr. This image has been digitally enhanced using AI.)

Sometimes the manongs would get dressed up on Saturday night to go on a date with their girlfriends, usually white women in their late thirties or early forties. They would leave in pressed slacks and clean shirts, shoes shined, and return on Sunday afternoon. I guessed it was something they had done for years, and the women knew the men well. Sometimes one of those relationships turned into a marriage, and the woman would join them on their migratory trek up and down California. Now and then, a child would be born, and the wife would stay in the camp to help the cooks. Those families had their own cabins in the camp, where the children looked after the camp’s chickens and sometimes helped with the fighting roosters the men kept for sport.

Many of the older men in camp also belonged to Filipino fraternal lodges and mutual aid organizations that had been part of California’s Filipino life since the manong generation first arrived. Some were members of the Caballeros de Dimas Alang, a Masonic-style lodge named after José Rizal’s pen name. Others belonged to the Legionarios del Trabajo, a labor brotherhood that provided a safety net for its members. Veterans in camp often connected through the American Legion, and many joined provincial associations, such as the Laoaganians from Ilocos Norte or the Tarlakenos from Tarlac.

New Wheels, a Camp Buddy, and Long Runs

(Image courtesy of Alex Fabros, Jr. This image has been digitally enhanced using AI.)

In February, one of the Filipinos in camp told me I could drive his old 1957 Chevy on my days off. All I had to do was fill the gas tank when I brought it back. That Sunday, I headed east to Yuma, Arizona, just to see what it had to offer. Another weekend, I crossed the border into Mexico, curious about the streets, markets, and cafés on the other side.

I didn’t make those trips alone. There was a young Filipino named Robert Baldovino, whose father had served in the U.S. Army and, before that, as a Philippine Scout. His family had gone to Germany with the Army, but because Robert was over 18, he was no longer considered a dependent. He had become a temporary farm worker instead. Robert wasn’t interested in college — just work — and we sort of became camp buddies. He came along on those weekend excursions, and we shared the quiet understanding of two young men trying to find their way, each in our own fashion.

When I wasn’t driving anywhere, I walked and ran a lot on my time off. I had an old pair of track shoes that cross country runners used, the kind with thin soles and light canvas uppers. On weekends, I would sometimes run the five miles into El Centro just to get a burger, shake, and fries at the A&W or the Dairy Queen. Afterwards, I’d go to the library to browse the books, taking my time among the shelves. A few hours later, I would run the five miles back to camp. I wasn’t fast, but my Timex watch, a gift from my mother, showed I was running the miles in under six minutes each.

Books, Music, and Poetry

During the week, I sometimes took the bus into El Centro to visit Imperial Valley College. In 1965, the college was still located on the El Centro High School campus while a new campus was being constructed. I wasn’t enrolled, but I wanted to see the bookstore, and it didn’t disappoint. I picked up history and science titles from the used section, and at the college library I bought withdrawn books on world history, the Spanish American War, and the Philippine Insurrection. That last one was my first real introduction to Philippine history.

Across the Imperial Valley, in towns like Calexico, El Centro, Brawley, and Westmorland, clusters of Filipinos lived in rented houses, shared apartments, and small labor camps on the outskirts of town.

Closer to home in Holtville, the public library was modest, part of the Imperial County Free Library system. Between that library, my growing stack of books, and the brand-new RCA portable record player I bought at Meyer’s Department Store (with two detachable speakers so I could play my 45s and LPs) the bunkhouse began to feel less like a stopover and more like a place where I could keep part of my own world alive.

In my spare time, in my corner of the room, I listened to my record collection at night and began penning poetry. I would play songs and then add my own words. I borrowed books from the library and often altered the words to better align with my own ideas. I soon mastered the art of writing poetry, because it’s not easy to write if you don’t understand how poetry is created. My journal began to fill with observations of camp life and working in the fields. I’ll be sharing that poetry later.

By the time we were ready to leave Holtville, I had the record player, a growing collection of records, and about twenty college books I had read cover to cover, now finally understanding all that I had neglected when I was a student. The book collection would continue to grow. I also had a box of letters from my girlfriend, who had been crowned Ms. Dimas Alang in January. I had taken a Saturday off that month to attend her coronation in Los Angeles, wearing my black suit. My parents drove down from Salinas for the event. I wasn’t her escort for the ceremony, but we had a few hours together after the event closed and a few more on Sunday before I had to head back to Holtville. I stayed with my cousin Mauricio DeLeon, who had been married to [Beverly Aadland], Errol Flynn’s last girlfriend, and returned the next day.

Heading North

The season wound down with the last Saturday in February. That morning, I packed my belongings: a blanket roll with sheets, my brand-new RCA record player, my RCA radio, and my collection of twenty college books. I now had several pairs of jeans, two pairs of boots, a light jacket and a heavy one, and two pairs of gloves, one for cold weather and one for work. I carried a wide-brimmed hat to which I had sewn an old handkerchief that hung down to shield my nape from the sun. My work shirts were thick, long-sleeved cotton, worn and faded from the weeks in the fields.

The dances were fewer, the bunkhouses quieter, the fields nearly bare. On Sunday morning, we loaded our gear into the crew truck. By that afternoon, we were on the road heading north to Gonzales, California, to harvest asparagus.

From the Memoirs of Alex S. Fabros, Jr.

Endnotes

1. “Weather Data for Holtville, CA, January–February 1965,” National Weather Service Archives, showing average low temperatures in the low 40s °F with frequent high winds.

2. “Holtville,” Imperial Valley Press, January 14, 1965; City of Holtville, Official Website, “About Holtville,” accessed August 5, 2025.

3. Author’s personal recollection; see also Carey McWilliams, Factories in the Field: The Story of Migratory Farm Labor in California (Boston: Little, Brown, 1939), 99–101.

4. McWilliams, Factories in the Field, 99–101.

5. California State Archives, “Farm Labor Camps, 1930s–1970s,” Series 4, Imperial County, Box 17.

6. Imperial County Free Library, “Holtville Branch History,” 1960–1970 files.

7. U.S. Department of Labor, Farm Labor Wage Rates, California, 1965, Statistical Bulletin No. 356 (Washington, DC: USDA, 1966), 14.

8. Author’s personal recollection of language loss in early childhood; see also Benito M. Vergara Jr., Pinoy Capital: The Filipino Nation in Daly City (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2009), 43–44.

9. Dawn Bohulano Mabalon, Little Manila Is in the Heart: The Making of the Filipina/o American Community in Stockton, California (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013), 202–205.

10. Erasmo Gamboa, Mexican Labor and World War II: Braceros in the Pacific Northwest, 1942–1947 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1990), 3–5.

11. Calexico Chronicle, “Bracero Program Ends—Growers Seek New Crews,” January 7, 1965.

12. Gene Fowler and Bill Crawford, Border Radio (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2002), 54–58.

13. Imperial Valley Filipino Community Association Minutes, 1964–1966, privately held by the Cruz family, El Centro, CA.

14. Oral History Interview with Reynaldo R., Brawley, CA, August 1988, Filipino American National Historical Society Archives.

15. California State Employment Service, “Farm Labor Job Orders, Imperial County, 1965,” File No. 65-IC-147.

16. Imperial Valley College Archives, “Campus History, 1922–1970,” accessed July 2025.

17. National Library of the Philippines, “Philippine Insurrection” (1899–1902), bibliographic entries.

18. “Mauricio DeLeon,” Salinas Californian, February 1965, society page note.

19. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Farmers’ Bulletin: Sun Protection for Agricultural Workers (Washington, DC: GPO, 1963).

________________________________________

Annotated Bibliography

• Bohulano Mabalon, Dawn. Little Manila Is in the Heart: The Making of the Filipina/o American Community in Stockton, California. Durham: Duke University Press, 2013.

Details Filipino American fraternal lodges, mutual aid societies, and community life — directly relevant to Imperial Valley’s Filipino organizations in 1965.

• Calexico Chronicle. “Bracero Program Ends—Growers Seek New Crews.” January 7, 1965.

Local coverage of the Bracero Program’s end and its immediate impact on Imperial Valley farm labor recruitment.

• California State Archives. “Farm Labor Camps, 1930s–1970s,” Series 4, Imperial County, Box 17.

Photographs and reports of camp construction and conditions similar to those in this memoir.

• California State Employment Service. “Farm Labor Job Orders, Imperial County, 1965,” File No. 65-IC-147.

Lists specific duties of cutters, boxers, and loaders, confirming the memoir’s work sequence.

• Fowler, Gene, and Bill Crawford. Border Radio. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2002.

History of “border blaster” stations like XERB AM 1090, with Wolfman Jack’s influence on Imperial Valley listeners.

• Gamboa, Erasmo. Mexican Labor and World War II: Braceros in the Pacific Northwest, 1942–1947. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1990.

Provides national context for the Bracero Program, useful for understanding the 1965 Imperial Valley labor market.

• Imperial County Free Library. “Holtville Branch History,” 1960–1970 files.

Confirms the existence and operation of the Holtville branch library during the time described.

• Imperial Valley College Archives. “Campus History, 1922–1970.”

Shows the college’s temporary location in 1965 before the move to its permanent campus in 1967.

• Imperial Valley Filipino Community Association Minutes, 1964–1966. Cruz Family Private Collection, El Centro, CA.

Documents Filipino dances rotating between towns in Imperial Valley.

• McWilliams, Carey. Factories in the Field: The Story of Migratory Farm Labor in California. Boston: Little, Brown, 1939.

Classic study mapping the seasonal farm labor circuit followed in the memoir.

• National Weather Service Archives. “Weather Data for Holtville, CA, January–February 1965.”

Climate data matching the cold mornings and windy days in the narrative.

• U.S. Department of Agriculture. Farmers’ Bulletin: Sun Protection for Agricultural Workers. Washington, DC: GPO, 1963.

Describes protective clothing practices used by field workers, including the hat and handkerchief described.

• U.S. Department of Labor. Farm Labor Wage Rates, California, 1965. Statistical Bulletin No. 356. Washington, DC: USDA, 1966.

Provides wage figures for hourly and piece rate work in lettuce harvests.

________________________________________

Suggested Reading List

• Almaguer, Tomás. Racial Fault Lines: The Historical Origins of White Supremacy in California. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994.

Explores race relations and labor hierarchies that shaped migrant workforces in regions like the Imperial Valley.

• Baldoz, Rick. The Third Asiatic Invasion: Empire and Migration in Filipino America, 1898–1946. New York: NYU Press, 2011.

Provides a foundational understanding of Filipino migration and labor patterns leading to the communities seen in 1965.

• Daniels, Roger. Coming to America: A History of Immigration and Ethnicity in American Life. New York: HarperCollins, 1990.

Includes discussion of post 1965 immigration reform and its impact on communities like those in Imperial Valley.

• San Juan, E., Jr. From Exile to Diaspora: Versions of the Filipino Experience in the United States. Boulder: Westview Press, 1998.

A critical look at the Filipino American experience, including labor and community life.

• Takaki, Ronald. Strangers from a Different Shore: A History of Asian Americans. Boston: Little, Brown, 1989.

A broad overview placing Filipino migration and work in the Imperial Valley within the wider Asian American story.

• Villasenor, Victor. Macho!. Houston: Arte Público Press, 1991.

A fictional but realistic depiction of Mexican and Filipino farmworkers in California agriculture, useful for cultural context

Alex S. Fabros, Jr. is a retired Philippine American Military History professor.

More articles from Alex Fabros, Jr.