Ninoy Is Dead, 1983

/Ninoy Aquino, being led away by the Philippine military on his arrival in Manila, August 21, 1983 (Source: The Kahimyang Project)

Madison, Wisconsin, Aug. 23, 1983

I did not have to read the headline again. I knew who that “Filipino Opposition Leader” was. I had just talked to him two days earlier before he enplaned for Manila and met his place in the country’s history.

Slumped on a nearby chair in WORT radio station’s newsroom, I tried to collect my thoughts. What should I do; what do I need to do? My training at the UP Institute of Mass Communications kicked in: Verify, verify. This could be a “kuryente story” (fake and malicious news), though not likely if it’s already circulating internationally. More likely, it was just me refusing to accept a possible painful reality.

If there was anyone outside his family who could confirm or deny this piece of undesirable news, it would be Steve Agular, Ninoy’s confidant, counselor. and doctor. A long-distance call to Boston was immediately answered by the good doctor. I had just identified myself when Steve in an anguished voice said “Totoo, Brod, totoo (it’s true, brod, it's true).”

[Ed note: Ninoy Aquino, Steve Agular and the author belong to the Upsilon Sigma Phi fraternity of the University of the Philippines, thus call each other “brod.”]

Ninoy Aquino, along with Upsilonian brods raising the Philippine Flag in Boston, in late 1981 (Sent by Victoria Villa on behalf of Victorino Villa '59)

The Journalist

Though short on details, there was enough in the teletype to make anyone realize the importance of this story. So, I called the station’s news director for directions and asked permission to break regular programming and air this tragic announcement. In the meantime, I told him that I was preparing a short announcement on the assassination for our disc jockeys and announcers to read in their respective programs.

There would be time later to grieve for this friend and fraternity brother.

Shortly, the station manager and the news director joined me at the station to inquire about the assassination. Both asked how well I knew Ninoy and asked what resources we had to do a story on him. I told them that I interviewed Ninoy over the phone just two days before he was assassinated. They listened to the interview tape.

Both agreed that we had good material, and that we should share and circulate the information that we had. Except for weekends, the station had a popular talk show every lunch hour. The station manager told me that I would replace the regular host of the next day’s program, which he said should include my interview with the murdered victim.

Petrified, I protested that I was just a chronicler of events but was never a talk show host. My protest was summarily dismissed with his comment, “There’s always a first time. This will also be good for our radio station.” He assigned two staffers to assist me in preparing the program. Lastly, he ordered me to prepare a profile of Ninoy to share with the radio federations to which our station belonged.

At this time of my life, I was a graduate student trying to earn a PhD in Development Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Short on financial resources, I worked part time driving a cab (among others) until a professor-friend found an opening in Madison’s progressive station WORT (89.9 FM). Initially, I was tasked with a variety of assignments from writing for the news department to filling in for absentee disc jockeys. After a year, I settled into writing foreign news daily and producing a weekly show on the Third World which featured news, music, interviews, etc.

The Fraternity Brother

I met Benigno S. Aquino, Jr. thru my father who was the chief engineer of the Central Azucarrera de Tarlac before, during, and a few years after World War II. Jose Cojuangco, Ninoy’s father-in-law and Cory’s father, and Eduardo Cojuangco, Danding’s father, were major stockholders of this sugar mill located in Paniqui, Tarlac.

Occasionally, I would meet Ninoy in Tarlac gatherings. And when I joined the Upsilon Sigma Phi, I would see him more often in our frequent fraternity fellowships. Later in life, I joined the news staff of Channel 5, the television affiliate of the Roces family media holdings. Ninoy was a frequent guest in its various information programs. Ninoy always liked to think of himself as a journalist, which he was when he was much younger. Frequently, he would hang around Channel 5’s newsroom and gossip with the staff whenever he guested in our many news programs or when he visited his sister, Lupita, who produced a telenovela in this station.

Jailed for several years during Martial Law, he was allowed to go into exile when he developed medical problems. Shortly after his heart bypass in the US in 1980, Ninoy decided not to return home and instead joined the North American opposition to Martial Law. He first made this widely known in a public appearance in Detroit, Michigan.

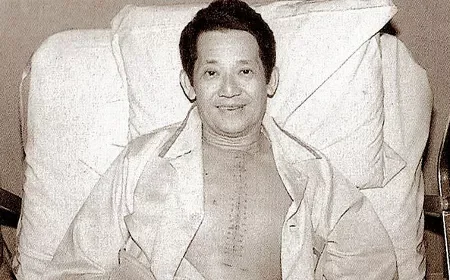

Ninoy Aquino at Baylor University Medical Center in Dallas, Texas, 1980 (Source: The Kahimyang Project)

Dr. Oscar Saddul, another fraternity brother, who was then doing his medical internship in that city, and I donned our polo barongs and joined the large crowd who welcomed Ninoy in Motor City.

When he saw us, he immediately enveloped us in a hug and started jabbering away in Kapampangan. He asked us to stay after the event as he wanted a long chat and a briefing on a variety of topics. We knew we were being recruited into his personal network of informants. We stayed in his hotel room till the wee hours of the morning, exchanging information on the Inang Bayan (Motherland) and the state of the opposition in the United States.

He asked about my personal status and speculated that as a grad student I probably had access to studies on national development. This was the confirmation that I was subtly being recruited to serve as his unpaid research assistant.

Aug. 20, 1983, and Parts of the Interview

The receptionist at WORT handed me a short note: “Call me ASAP.” Signed Brod ‘50. We had adopted the practice of the opposition to Martial Law of not mentioning names in our communications. But it was amusingly obvious to me as to who authored the note. As neophytes, we had to memorize the names and the year our seniors joined our fraternity.

I called the Aquino home in Boston. It was Ballsy, his oldest daughter, who answered. She told me that her father had already left the city and was at his sister Lupita’s place in California. I called him there.

The Aquino family in Boston (clockwise from top left): Cory, Ninoy, Ballsy and Kris (Source: philstar.com)

After the salutations, he immediately said “UUWI NA AKO (I’ll be going home).”

After asking “when,” the journalist in me, asked, “Puede bang last interview (Can I have a last interview)? “

A little over a month earlier, Upsilonians all over the US East Coast and some from elsewhere gathered in Dr. Agular’s Boston residence in an impromptu fellowship. It was during this occasion when Ninoy told his fraternity brothers that he was thinking of going home.

As I got my recording equipment ready, I tried to recall the barrage of questions asked during the last Boston gathering. To the “why now” question, Ninoy said he had learned that the president was not in the best of health and had been sick for some time. Ninoy always had a wide range of informants; even when he was in jail he maintained a network which included government employees and even some in the military. One of them passed on to him information of “a failed kidney transplant.”

He feared if the president suddenly died, chaos may result from “the power vacuum” that would follow. This, he emphasized, could be avoided. He would willingly work with the authorities to prevent the ensuing disorder.

I asked if him if he seriously thought that the person who jailed him earlier would now collaborate with him. “He is a Filipino,” he answered obliquely. And I asked, “What if he throws you back in the stockade?” He replied “The way things are in the country my return will provoke discussions on Martial Law and my incarceration again. That’s good enough for me.”

Using the vocabulary of the day, I asked the dreaded question, “What if you are ‘salvaged’?” “No, I don’t think he would give such an order.” Then he repeated his addendum to another journalist who asked the identical question; waxing “romantic,” he explained why:

“He (Marcos) will be lonely without me.”

Back to Aug. 23, 1983, and After

Even before the day was over, because of the short news blurbs on the assassination which also promised the airing of an interview with the victim, WORT started receiving request for copies of the interview from our colleagues in other media.

This made me extremely nervous about the following day’s talk show. I had been out of the country for a while and may not be up to date on developments and I speak with a distinct Filipino accent and so I “kinda/sorta chickened out” and invited heavy hitters. A long-distance call to the Bay Area in San Francisco to Joel Rocamora, my former UP grad school professor, got a positive response to my invitation for him to join the following day’s talk show. Another long-distance call to the pundit, Walden Bello, got the same response.

The talk show went well and was even aired again later the same day, and even other media agencies replayed it. Newspapers and other media continued reporting on the assassination for weeks. Perhaps, running out of other sources, some news agencies started interviewing the chronicler. I even got to enjoy a few Andy Warhol moments from some listeners. This included a friend from the Pacifica Radio Network who was so impressed he offered me a job. But no, I was still in grad school, maybe later.

Weeks later Steve Agular called me; he heard the talk show. He thought a copy of the interview would be a nice gift to the Aquino family and asked for a copy.

When the tragedy happened, I thought getting the word out about what was happening in my country was extremely important. I took every opportunity to do this including lending out my Ninoy interview cassette to whoever wanted to do the same.

There was a long queue of borrowers from my colleagues in media. I accommodated them. Those days left me little time for myself; work, school, and an occasional speaking engagement left me frazzled. I became careless.

I wanted to accommodate Dr. Agular’s request and searched high and low for the interview cassette. It wasn’t in my office desk, and neither was it in my school desk. I started panicking. I did my utmost best, but still I couldn’t find it. All that was left was the hope that the last borrower would return it.

The Aquino family never got a copy. Dr. Steve Agular passed away a few years ago. All I had left was a memory of my own stupidity.

Slumped on a nearby chair in WORT radio station’s newsroom, I tried to collect my thoughts. What should I do; what do I need to do?

Postscript

Five years later, in 1988, I moved to New York City. Now teaching, I wanted to keep my credentials as a journalist and so I sometimes wrote for the news department of WBAI, the flagship radio station of the chain Pacifica Radio Network. This network favors and focuses on the different ethnicities in the US. It knew that there are over a quarter of a million Filipinos in the New York City area. A year later, cognizant of its mandate, I was asked to produce and host a weekly radio show, Philippines in Focus.

The Big Apple was too much even for this Manila Boy; four years later I still straddled the two worlds of academia and journalism. But I was now covering events in another country. Teaching and reporting events in foreign countries were never on the radar when I was a student at UP’s Plaridel Hall. Many helped me along the way including a fraternity brother who profoundly believed that the Filipino “was worth dying for.”

Four decades later I still wonder where that interview cassette is, and I still anguish over my stupidity.

Sorry, Brod and thank you. I owe you.

This article was originally written for the Upsilon Sun.

Chibu Lagman taught Latin American Studies at the University of Alberta and the University of the Philippines. When not teaching, he worked as a news correspondent covering events in Latin America. He has either visited or lived in almost all the countries in Ibero America. He still commutes between Manila and Abya Yala (the Americas). Chibu is also a graduate of the Culinary Institute of America (CIA).

More articles from Chibu Lagman