Where Are Imelda’s (the People’s) Jewels Today?

/The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of this publication.

The PCGG is a government agency especially created by the Cory Aquino administration after the ouster of Ferdinand Marcos, to trace and recover ill-gotten properties, monies and assets stolen by the Marcoses and their cronies during their 21-year rule. The PCGG is still in operation today, 31 years later; however, it has become suspiciously less visible and active.

There were two conflicting statements released by the PCGG a year ago. First was a general press release (carried over the wires) in which then-PCGG commissioner Andrew de Castro hoped they could get an auction going before his term ended in June 2016. This seemed to indicate that ownership issues had finally been resolved (Imelda had filed a few suits contesting the seizure of “her” jewelry) and that indeed they could be auctioned off and monetized by the government.

La Viuda Loca Marcos flaunting her arrogance and, well, jewels. Where are the jewels today?

This was followed shortly by a smaller clarification from Richard T. Amurao, then acting PCGG chairman in early 2016, that ownership of some pieces was still in question and had actually not cleared litigation.

So why was there a “rush” in getting the jewels to auction in 2016? The PCGG further clarified that the impending actions had “nothing to do with the upcoming elections” in which Imelda’s son, Bongbong, was running for vice-president. But wiser heads knew that that was precisely the reason for the push forward. There was the strong possibility that Bongbong would emerge as vice president—and nearly did—and the Marcoses would move heaven and earth to repossess their mother’s jewels, among other actions.

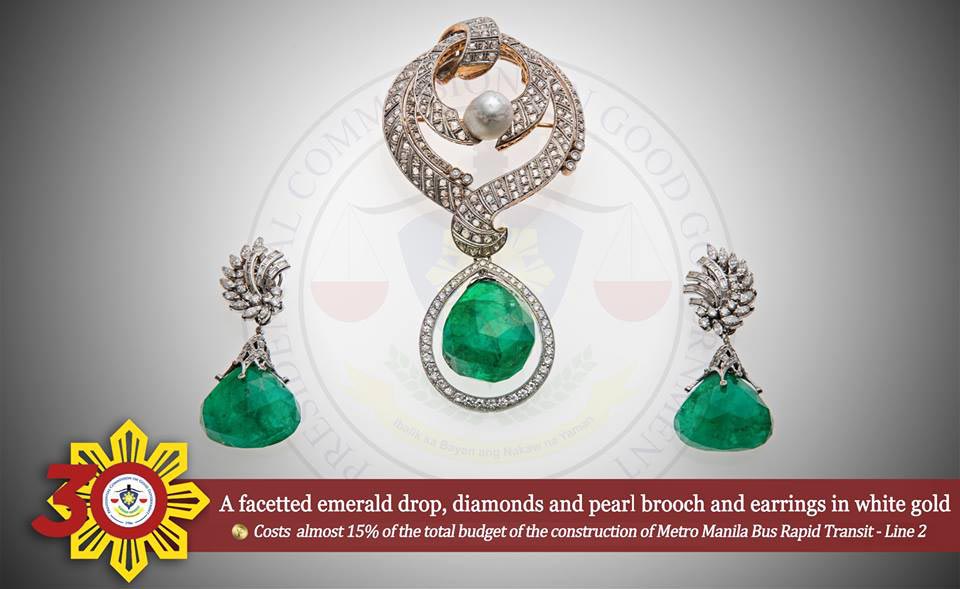

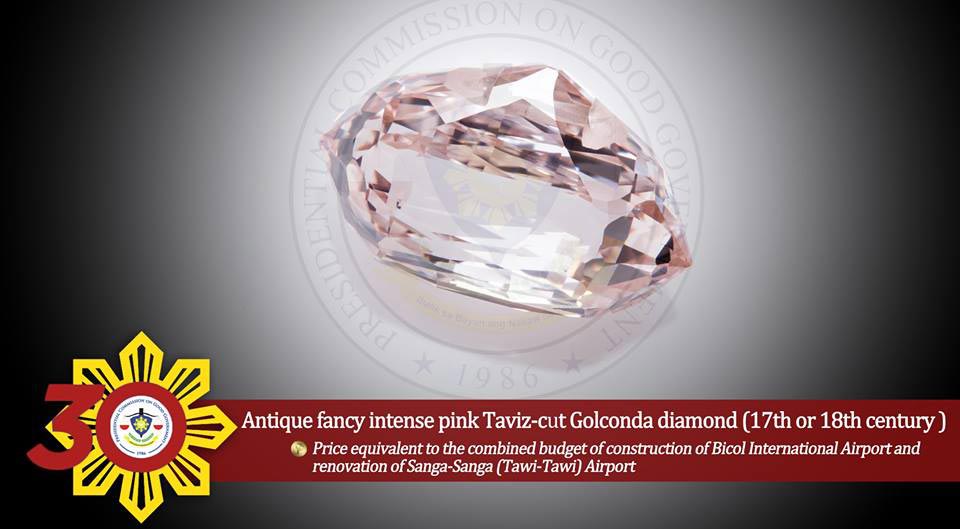

Then as late as April 2016, the PCGG got into the electoral act by releasing images of the more select jewels on the Internet and reminding the voters what the equivalent value of the jewels could mean and purchase for the common Filipino. Some of these “reminder” images from the PCGG are recreated in this article:

Other events followed quickly. Rodrigo Duterte was elected president and installed in June 2016. Bongbong Marcos came up some 200,000 votes short of the vice presidency. Then it all became quiet on the auction front. All of a sudden, it seemed like there was a total news blackout of a much-heralded international auction. What happened?

The Hoard

First, let’s understand what comprises the confiscated jewelry. The hoard is divided into three “collections” supposedly under three different custodianships.

One, the “Hawaii” collection, which Imelda hastily took with her on their flight out of the Philippines on February 25, 1986 to Hawaii. These were among the Marcoses’ personal possessions—cash, bonds, certificates, gold bars, weapons and jewelry—which were packed in Pampers’ boxes but confiscated by U.S. Customs at the Hickam Air Force Base in Honolulu. These were ultimately returned to the Philippines. The PCGG controls this collection.

One of the three collections – possibly, the “Hawaii” collection.

Two, the “Roumeliotes” collection. Two weeks after their ouster, when there was still chaos, with the Marcoses and cronies trying to hide everything they could from the new Cory Aquino government and its new allies around the world, an anonymous tip to Customs at Manila International led to the interception of one Demetrius Roumeliotes at Manila International leaving the Philippines on March 9, 1986.

A package addressed to Imelda Marcos in Hawaii, containing eye-popping jewels, was found on his person. But then Roumeliotes and his wife quickly dissociated themselves from the fabulous hoard, and thus were allowed to leave Manila quickly.

The “Roumeliotes collection,” as it was so christened after the interception, is the most valuable of the three and was turned over to the BSP (Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas) for safekeeping. There are some 60 pieces in the “Roumeliotes collection.”

Why were the pieces in the Roumeliotes collection left behind to be sent for later? Many pieces were kept in other banks’ safety deposit boxes. Since the Marcoses escaped in the middle of the night, Imelda did not have the logistics to send agents to the bank(s), which were closed, and bring the jewels to the fleeing family. There were also pieces in the safekeeping of Imelda confidantes (like Madame Cao Ky, former first lady of Vietnam, for example).

As the events of February 25, 1986 prevented Imelda from making a clean haul of precious possessions, it took a while for her relatives and inner circle (among them, Dr. Teyet Pascual, her Manila jewelers Liding Oledan and the Panlilios, Glecy Tantoco, etc., who were also all busy attending to their own disappearing acts) to get together and hatch a discreet “escape” plan.

Who could they find that was trustworthy to spirit the collection out of Manila? The choice fell on the little-known Roumeliotes, a high society hairdresser. But where did that anonymous tip come from? Obviously, from someone in the inner circle.

One of the smaller baubles, from the Roumeliotes collection. Ruby and diamond bracelet with ten 5 cts. pigeon blood red rubies surrounded by smaller rubies and diamonds in yellow gold. 1.5 inches wide X 8” long. Marked Van Cleef & Arpels, NY. Item# 36, page 5 PI customs list. (Photo courtesy of Diana Limjoco)

The third part is the “Malacañang Collection”—composed of what was left behind by the Marcoses at the Palace. The cheaper jewels, semi-precious stones, costume jewelry, dozens of Rolex watches and the like—the kind which the dictators would hand out as gifts—make up most of the third collection. That these were left behind in the Marcoses’ hasty departure, would make this collection the least valuable (valued at under $154,000) and most expendable.

Gaudy and Showy

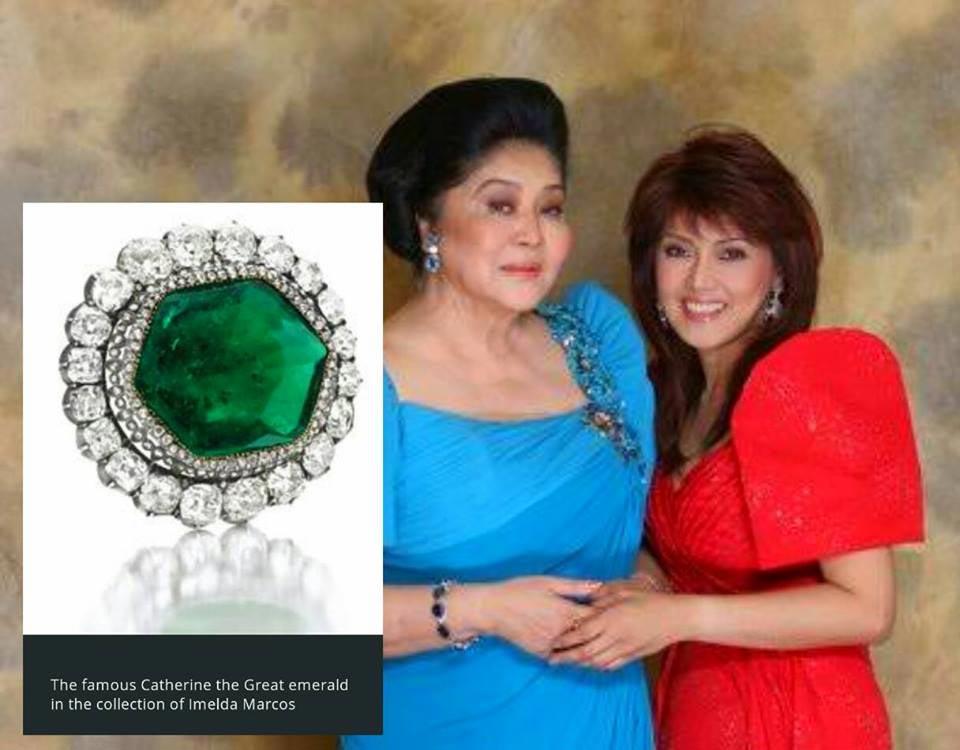

For the most part, Imelda’s jewelry is slightly on the gaudy and showy side—stones and settings of such high wattage that only a blind person would miss them. There are some historic pieces, however, like those with a provenance of the Romanovs, the last ruling imperial dynasty of Russia (whose, coincidentally, centenary of their overthrow, is marked this year, 2017):

The above emerald was part of a set that was mentioned most nostalgically in the famous “Anastasia” play as “Figgy’s emeralds. Figgy” was the Romanovs’ nickname for their ancestor, Catherine the Great. Romanovs, Romualdezes, Roumeliotes—was there some sort of unholy trinity alliance?

The Tiara of the Armory of Empress Marie Federovna, Nicolas II’s mother. Like Imelda, this was one of the few pieces that the Dowager Empress escaped with when she left Russia in the protection of a British warship, in 1918. Like many of the deposed royals, as their circumstances diminished, Empress Marie was forced to sell her jewels. For years, the Duchess of Marlborough of the UK, owned it until sold at auction in 1978. Shortly thereafter, it quietly ended up in Imelda Marcos’ possession.

What has delayed the sale of the jewels? There are a few reasons.

One, obviously, there is a turf war going on between the three agencies and the larger shadow of President Duterte. The Duterte administration has made no bones about its very blatant partiality for the Marcoses, and with its other actions is now bordering on the dictatorial, looms darkly over the whole situation.

As early as July 2001 (during the Gloria Macapagal administration), the inter-agency turf war over control of the hoard—specifically that RP Customs was responsible for scuttling all attempts at a comprehensive and joint auction—was recognized in an Op-Ed piece in the Philippine Star by “Gotcha” columnist Jarius Bondoc:

“Since the 1986 confiscation, PCGG officials had tried several times to get Customs to agree to a joint inventory and cataloguing of the jewels. On all occasions, certain interests and rules invoked by both sides prevented any cooperation. After the 1994 Supreme Court ruling, PCGG also asked Customs several times for a joint auction. The agency bosses would always come to an agreement, but somehow subordinates down the line managed to mess things up. If it was only turf war, Malacañang easily could have intervened, then credited the officers for a job well done and apportioned the revenues to both Customs operations and PCGG's beneficiaries under the agrarian reform law... Customs officers still refuse to hold a joint auction... They cite myriads of supposed technical and legal kinks, all minor and easily solved, though. Weeks ago, a Malacañang official went to Bangko Sentral for a look-see of the jewelry and covering documents. Customs men refused to let the Malacañang official in. Higher and new Customs officials are wondering: could it be because the jewels are no longer complete, or have been replaced with imitations?”

(Source: Diana Limjoco’s blog)

Another 16 years later, in 2017, this apparently is still the case.

Second, can the three agencies get on the same page and trust Sotheby’s and Christie’s? When the Ayala Museum and NYC-based Asia Society mounted their Philippine gold exhibit in New York in 2015, a most confidential source shared that the Bangko Sentral was most loath to loan its half-dozen pieces to the traveling exhibit, even with the highest insurance taken out for the show.

If those were merely a handful of pieces loaned out in 2015, what more a collection of world-class jewels? Before a major auction can proceed, Sotheby’s and Christie’s will need to take possession of the entire lot for at least six months, authenticating the jewels, their provenance, cataloguing them and preparing properly for a grand international auction. That would probably be the last time the jewels would be in Philippine government hands.

The Pink Diamond. As small as a one-peso coin (24.90 cts), this intense, antique pink Golconda diamond is the most valuable item in the Hawaii Collection. The stone was originally thought to be a paste copy until a late closer inspection revealed it to be the real thing. This gem’s price equivalent alone is worth the combined construction of Bicol International Airport and the renovation of Sanga-Sanga (Tawi-Tawi) airport.

Claw-Back from Martial Law Human Rights Victims

There is also the specter of liens being placed on the jewelry and/or “claw-back” claims by Robert Swift, the Philadelphia-based attorney on behalf of his clients, the human rights victims of Marcos.

As precedent, Swift had already succeeded in securing some of the profits made in the sale of two plundered canvases: Head of a Woman by Pablo Picasso (1954), and the controversial Monet painting, La Bassin aux Nympheas, which Imelda’s gal Friday in New York, Vilma Bautista, had fenced illegally.

Armed with the outstanding judgments of the Hawaii courts, Swift was able to secure around $10 million from those two pieces – even though that sum is a mere drop in the bucket of the total $1.9 billion judgment award made by the courts in Honolulu.

Regardless of where a possible auction may eventually take place—New York, Geneva or HongKong—Swift will still be able to attach some of the proceeds since the two auction houses have a major presence in New York. Thus, is the current Philippine government prepared to surrender at least 10 percent of the proceeds of the auction to Swift and the human rights’ victims?

One of the more reliable sources of the state of Imelda’s jewels is freelance photographer Diana Limjoco who was given unprecedented access to photograph major parts of the hoard in August 1986 and 1988 when the first valuations were made by Christie’s and Sotheby’s.

Strangely enough, on her blog, http://jewels-of-imelda-marcos.blogspot.com/ , Limjoco cites encounters with Imelda Marcos at parties in Manila where Imelda actually asked the outsider (Limjoco) if she had any news of “her” (IRM) jewels. Up to late 2015, Limjoco has kept watch over the matter closely.

Intrinsic Value

In the greater scheme of things, the three collections’ intrinsic value has been assessed at anywhere from $20 million conservatively, to as high as $30 million, with inflation taken into consideration. On a good auction day, if marketed properly, they could easily gross $60 million. Optimistically, it could even reach $80 to $90 million.

That would make it the second highest sale of a private jewelry collection sold at public auction. Holding the record is the sale of Elizabeth Taylor’s jewels, sold by Christie’s in New York in December 2011. The 80-odd lots of La Liz’s baubles, white diamonds, etc., fetched a jaw-dropping $137,235,575.

What has happened in the meantime? Nothing; and that has been most disturbing. After much ballyhoo last year, and the virtual reality exposure campaign, it was as if a complete news blackout was imposed on the subject once the Duterte administration took power.

Around July of last year, when planning for a trip to Manila in September and hoping to have a face-to-face interview with the PCGG, I contacted the Commission and tried to get the ball rolling. Via their Facebook page, I got one reply that the party to contact was research@pcgg.ph.gov.

After further attempts at follow up, as my trip to Manila neared, I never even got a second reply from the agency despite claims on its website to be “transparent and open.” But as late as November 2016, the PCGG Facebook page still carries fresh entries from the agency. While the posts on its website try to keep the public abreast of what’s going on with them, there is nothing new about the disposition of the Imelda jewels.

My last query of November 17, 2016 is still on their FB page but has gone unanswered. Repeated attempts to gain updates from the PCGG have also earned zero responses. The silence has been quite deafening and ominous.

Having gotten nowhere with the PCGG, on a whim I went directly to the horse’s mouth. I contacted Christie’s personnel in November 2016, most specifically François Curriel, who had hands-on access to the jewels in 1986, and is now head of Christie’s Asia operations.

Tight-Lipped

As tight-lipped and circumspect as PCGG has been, Christie’s was completely professional and transparent regarding my query, with M. Curriel also copying David Warren, his boss in London. Mr. Warren replied similarly to me in detail that Christie’s had no news on Imelda’s jewels, but that they would share such information with me in the future, as soon as they possibly could.

I believe Christie’s would be the front-runner if ever an auction pushed through since it handled the previous Marcos-plundered goods--the paintings and the silver—to the satisfaction of the Philippine administrations then. Almost providentially, Christie’s just came out with a luxury coffee-table book this past December, Christie’s: The Jewelry Archives Revealed, written by Vincent Meylan with a Foreword by the aforementioned M. Curriel. Could this be a portent of things to come vis-à-vis the Imelda jewels?

Even though in her blog, Diana Limjoco says that the PCGG assured her as late as October 2015 that all the collections are still “there” and “intact,” one cannot help but echo the above-quoted Mr. Bondoc’s skepticism on the matter.

Have paste copies of the jewels been made? One shouldn’t be surprised if they were. One should be mindful of the depths of deceit that the Marcoses are capable of. In late 2014, several canvases that were on the PCGG’s list of missing masterpieces were seized from the Pambatasan office and various homes of then-Congressperson Imelda Marcos. What PCGG agents encountered in their raids, however, was confounding.

Imelda had had several copies of the truly valuable paintings made and installed in her office and in the various homes. The originals, of course, were safely sequestered away and, like the Picasso and the many missing masterpieces, may not see the light of day for awhile. As if to prepare for such a day of reckoning, Imelda was ready to thwart the law once again with mere copies—knowing that the Philippine government does not have the wherewithal to detect old masterpiece fakes and would have to engage expensive, outside foreign help to do so. Again, confound and confuse the Filipinos.

Thus, it would not at all be surprising if with collusion with the Duterte administration, Imelda and her allies were able to have copies made of her jewels as substitutions.

How ironic that the Bangko Sentral has custody of Imelda’s ill-gotten jewelry. It was there, some sixty-odd years ago, that Imelda started her Manila sojourn as a clerk; and now, its very vaults guard the ill-gotten jewels that the once-innocent lass from Tacloban had acquired and would very much like to get her hands on again. And if it has become known in the inner circles of power that sleight-of-hand has occurred, then a legitimate, international auction will no longer be possible.

If so, the Filipino people have once again been made a patsy and taken for a ride.

Again, justice delayed is justice denied. And if you count the interest that should be accruing had these assets been turned into more productive investments, the Filipino people are out another $80 to $100 million again. If so, the Marcoses have raped their countrymen one more time.

Sources:

http://news.abs-cbn.com/nation/02/18/14/slideshow-marcos-jewels

http://www.rappler.com/nation/47862-court-forfeits-imelda-jewels-for-ph

https://news.artnet.com/art-world/imelda-marcos-paintings-brooklyn-warehouse-763271

http://www.cnn.com/2016/02/16/luxury/imelda-marcos-jewelery-auction/

http://www.djl.net/jewels/html/feedback.html (Photos of jewelry courtesy of Diana Limjoco)

http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/864849/sc-bars-marcoses-from-cabuyao-property

Myles A. Garcia is a Correspondent and regular contributor to www.positivelyfilipino.com. He is also the author of two books: Secrets of the Olympic Ceremonies, and Thirty Years Later . . . Catching Up with the Marcos-Era Crimespublished last year. His first stage play, “23 Renoirs, 12 Picassos, . . . one Domenica”, will be getting a fully Staged Reading in San Francisco on May 22nd.

More articles from Myles A. Garcia