Leapfrogging a Revolution

/Book Review:

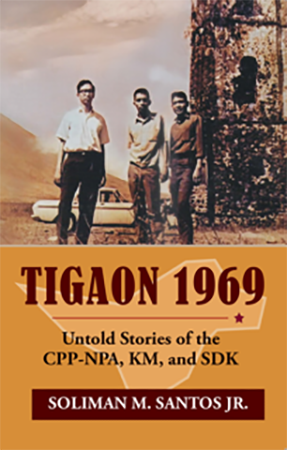

Tigaon 1969: Untold Stories of the CPP-NPA, KM, and SDK by Soliman M. Santos, Jr.

Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2023.

Naga City Regional Trial Court (RTC) Judge (ret.) Soliman Santos—or simply Sol to his colleagues and comrades—had been judiciously following up on the review of his book that I had promised for quite a long while. I’ve been reading it “in small increments,” I said.

His reply, likely his way of showing patience with my glacial pace, was that “later generations of activists” who read Tigaon 1969: Untold Stories of the CPP-NPA, KM, and SDK may find it “more difficult than usual, say, compared to reading To Suffer Thy Comrades” (my book on the CPP-NPA internal purges).

Tigaon 1969 has “many pre-martial law interrelated facts (especially names and places in another unfamiliar region), including, and in correlation with, contemporaneous KM-SDK and even intra-SDK dynamics.” KM is the militant organization Kabataang Makabayan (Nationalist Youth), and SDK is Samahang Demokratiko ng Kabataan (Democratic Youth Organization). In friendly competition, both organizations effectively recruited tens of thousands of students and young people and mounted massive protest actions against President Marcos Sr. in the early ’70s.

Sol is right—partially. It took a long stretch to reach his book’s finish line, not so much due to generational unfamiliarity as to a surplus of information. Tigaon 1969 does not proceed chronologically, because each fact or anecdote is surrounded by myriad details: who was involved, where it happened, sources of information, claims and counterclaims, etc. It seems Sol felt the urge to say everything about something, often in one sentence! Poring over this encyclopedic left history focused on an obscure locality within a region that Sol evidently loves, I quietly wished he had punctuated it with more periods—more bite-sized pieces. But perhaps that’s just me, an admitted slow reader with attention issues.

That minor quibble out of the way, Tigaon 1969 is as direct as a title can get. It is a historical opus asserting the “true origins” of the revolutionary movement in the Bicol region. It challenges the official narrative of the Communist Party of the Philippines–New People’s Army (CPP-NPA), which pegs Bicol’s revolutionary beginnings in 1970, with the return of Bicolano student activists from Metro Manila. Most prominent among these was Romulo Jallores (later Kumander Tangkad), who famously led a team of youth protesters that commandeered and rammed a firetruck against the presidential palace (Malacañang) gates at the height of the First Quarter Storm (FQS). He later commanded the first NPA unit in Tigaon and was killed in battle—in dramatic fashion, as depicted graphically in the book. The NPA unit in Bicol that continued to grow in strength during the martial law years under Marcos Sr. was named in honor of Jallores.

Robert Garcia (right) with Judge (Ret.) Soliman M. Santos, Jr., author of Tigaon

Revolutionary Seeds

Santos, however, insists that the revolutionary seeds in Bicol had been planted in Tigaon, Camarines Sur, a year earlier, which he emphasizes needs to be acknowledged in official Party history. The initial effort was carried out by a “First Five” expansion team, including CPP Politburo member Ibarra Tubianosa (from Sorsogon) and Francisco Portem (from Albay), along with three Tigaon natives: Marco Baduria, Nonito Zape, and David Brucelas. The five, all members of Kabataang Makabayan (KM), were deployed to Tigaon for “mass work” and organizing.

Tigaon was selected because it epitomized the country’s “semi-feudal and semi-colonial society.” Dominated by large landed estates held by wealthy families, the town represented an exploitative environment conducive to organizing landless peasants—providing fertile conditions for revolution. After months of organizing in Tigaon, however, the central CPP leadership ordered the team to pull out in late 1969 after a parallel effort on Negros Island experienced catastrophic failure (the so-called “Negros debacle”). Two of the Tigaon natives, Baduria and Zape, defied the directive and continued organizing in the area despite being cut off from the Party center. This act of local agency and perseverance, Santos argues, was the true beginning of the revolutionary movement in Bicol, without which the later, officially recognized armed struggle would not have been possible.

Joma Sison’s Reaction

What was the reaction of the late Jose Ma. Sison, CPP founder, to Santos’ assertion? Interestingly—as gleaned from the email exchanges between the two—Sison was defensive and even combative. He denied the claim that the CPP stopped supporting the initial expansion efforts in Bicol in 1969. He insisted that the Party supported the expansion efforts of Jallores from 1970 onward, a breathtakingly erroneous argument that misses the mark: the bone of contention was 1969, not 1970. Either Sison had totally forgotten, completely ignored, or rejected the legitimacy of pre-1970 efforts. Sison somehow changed his tune late in life, finally recognizing the initiatives of Baduria, Zape, et al. via a Facebook post in 2016.

To the casual observer, this contention might matter very little. Whether the revolution in Bicol was started by Jallores et al. in 1970 or by Baduria et al. in 1969 may seem inconsequential. But for those who value the movement’s impact on the country’s history, it is not only a matter of giving due credit, but also a matter of truthfulness.

Tensions

The book also elaborates on the movement’s strategic internal debates of the period. A key conflict was between the “wave upon wave” versus the “leapfrog” strategy for movement-building. The former involves initial base-building followed by systematic, contiguous expansion from the base, favored by the central leadership early on. Leapfrogging involves jumping to strategically chosen areas with ripe objective conditions for germination and expansion, such as the actions undertaken in Negros and Tigaon. The Party’s initial preference for the wave-upon-wave option eventually gave way to the leapfrog mode, as the country’s archipelagic, multi-island features favor decentralized operations. The CPP-NPA’s expansion and strengthening in many regions, albeit at varying levels, proved this to be correct.

Another organizational tension that emerged in the Tigaon case involved the rivalry between the two leading militant youth groups, KM and SDK. It foreshadowed the split within the CPP (Reaffirmists vs. Rejectionists) two decades later. Sison and his supporters had themselves split from the old Partido Komunista ng Pilipinas (PKP). Santos stresses that the history of the Philippine revolutionary movement, as elsewhere, is a history of schisms.

KM started off as the youth arm of the PKP. When Sison was expelled from the Party, he brought with him loyal KM followers and formed the CPP in 1968. In 1969, he forged an alliance with Bernabe Buscayno (Kumander Dante), who was then leading his own guerrilla army, thus forming the formidable bond between the CPP and the NPA. KM continued to recruit and expand as a radical youth organization, but some members chafed at what they perceived to be Sison’s authoritarian leadership and formed the SDK. The latter placed greater emphasis on education and critical thinking and encouraged independence and initiative.

SDK stalwarts constituted the “second wind” of the Bicol revolutionary work in 1970, with the arrival of a reinforcement group from the SDK University of the East (UE)–Taytay chapter, which included Romulo Jallores. This also brought a new set of tensions, specifically on the question of whether to reconnect with the CPP central leadership or retain the autonomy the new SDK group insisted on. The Tigaon locals, led by Baduria and Zape, voted to seek renewed guidance from the CPP center and compelled the “renegade-ish” SDK Taytay group members to leave the guerrilla front. Hence, the CPP Tigaon front was reestablished by early 1971, followed by the formation of the local NPA unit, which began to carry out acts of “revolutionary justice” (liquidations of “bad elements”) and land reform.

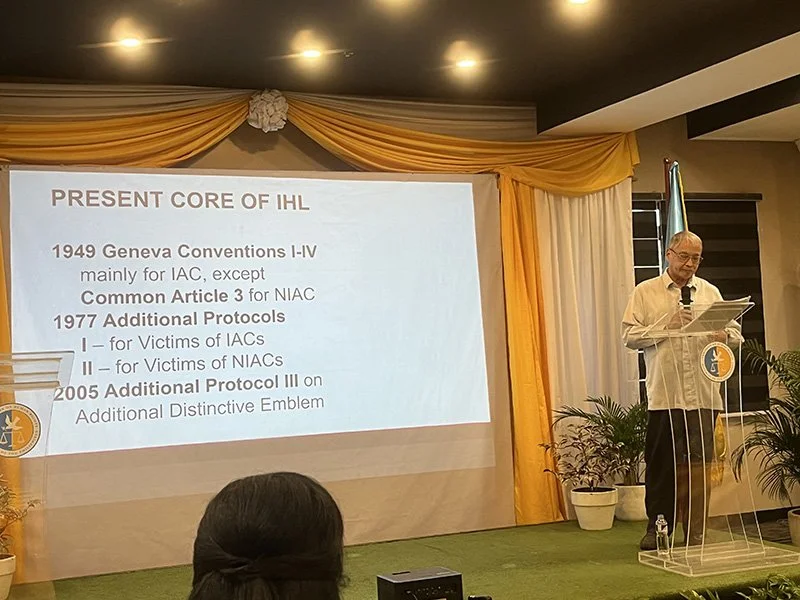

Judge (Ret.) Soliman M. Santos, Jr.

Armed Revolution, Anyone?

Midway into the book, Santos dives deep into introspection. Armed revolution: is it still a viable call? We know that the fundamental problems of society remain—massive poverty, inequality, injustice, corruption. The author accepts that the long, hard fight for “systemic change” continues, but laments the enormous human costs of waging an armed struggle. For all the revolutionary movement’s noble aspirations, he wryly observes its predilection for physically eliminating those who no longer toe the line. He cites, as an example, a “CPP directive in mid-1971” to a local Party committee to monitor a certain “revisionist” group operating within their area of responsibility, “with an order to liquidate (shoot-to-kill) them.”

Santos criticizes this “surprisingly early resort…to ordering the physical liquidation of inner-Party dissenters,” pointing out that this was precisely the kind of intolerance Sison accused the old PKP of exhibiting. This witch hunt, Santos proposes, was a “precursor of sorts” to the bloody internal purges of the 1980s that led to the torture and execution of thousands of suspected deep-penetration agents (spies). Was the spilled blood all this worth it? Santos offers no answer, as it is not “the subject or coverage of this book,” but invites readers to consider the question in light of our struggles in the present.

Contentious History

Santos concludes by arguing that history evolves, as expressed by Dominic Caouette in his Foreword. Tigaon 1969 contributes to this evolutionary process not only by correcting and complementing the existing record, but also by highlighting its contemporary relevance. He compares this contentious history to the current political landscape, where social movements grapple with the restoration of the Marcos family to power in 2022.

This act of local agency and perseverance, Santos argues, was the true beginning of the revolutionary movement in Bicol

The book is relevant to present-day activists and revolutionaries, whichever bloc they align with. At the very least, they would benefit from the meticulous research poured into the project. More than this, Santos poses his thesis as a necessary problematique for revolutionary theorists who hold that the masses ultimately decide their fate and are therefore responsible for the outcome of history. Historians, too, will gain a deeper appreciation of local histories and how they help shape national narratives.

To be sure, this remains a work in progress, and we have not yet reached “the end of history.” It is incumbent upon us to continue rewriting and refining our understanding of the past, to better interpret the world—as a form of self-help for people like us who are bold, and “foolish enough,” to try to change it.

Robert Francis “Bobby” Garcia is the author of To Suffer thy Comrades: How the Revolution Decimated its Own. He was Undersecretary at the Office of the Political Adviser for President Benigno S. Aquino, Jr. He previously worked at the UN, Oxfam, ASEAN, and other international organizations. He is the Board Chairman of the Institute for Popular Democracy (IPD) and Founding Chair of the Peace Advocates for Truth, Healing, and Justice (PATH), a human rights organization.

He presently leads the Technical Assistance Team of Governance in Justice (GOJUST) II – Human Rights, supporting the Commission on Human Rights (CHR) through funds from the European Union (EU) and the Agency for International Development Cooperation (AECID) of Spain.

More articles by Robert Francis Garcia