Hello, Dali: Salvador, Venus and Me

/A self-portrait with his trademark moustache and melting clocks.

When I was a callow teenager still in Manila, I had this well-to-do aunt who had a limited edition, watercolor print by Marc Chagall. I was filled with both great admiration for it and secret envy because it was a beautiful object d’art, something only really rich people acquired and possessed.

When I moved to New York, older (24), ambitious but still naïve , I wanted to invest in some art. I was living in a major art center; I had some credit, and doggone it, I was going to get myself some “lucrative” fine art if it killed me. I even joined a Print Collector’s Club of some sort, whose members supposedly had first crack at new, limited-edition prints put out by promising artists. I wanted to fill the walls of my modest apartment with some “significant” artwork that I could afford at the time.

Dali photographed with his menagerie of rare animals; left, walking an anteater in Paris and, right, an ocelot in New York. I doubt that he would have been allowed to keep, much less exhibit, these endangered animals as part of his public persona.

At first, I could only afford posters like this below which cost $5 (or was it $10?), which I thought was already a lot of money in those early days.

The first Dali I could afford -- a $5 poster.

Sometime in late winter 1974 (probably March or April 1974), I was in this art gallery in Greenwich Village, which called itself a “Salvador Dali dealership.” There I was facing a treasure trove of signed, authentic Dali works with affordable prices. Wow! I thought, I could actually afford some of these. One, priced for only $199, caught my eye. I couldn’t resist and let the opportunity slip away from my hands. So, I committed and bought a limited-edition Dali print, my first “serious” work of fine art acquisition.

I treasured that print and reveled in its ownership. The next time I went home in Manila in 1977, I had a frame custom-made for it. Over the next few decades, it hung in my various apartments and homes, occupying a special place above my headboard. Frequently, I would look at it and have mixed feelings about whether I had actually purchased an authentic piece of art.

Starting in 1984, I moved all over the place—LA, Atlanta, finally, the San Francisco Bay Area-- taking my Dali with me, but also losing its Certificate of Authenticity along the way. In the meantime, Señor Dali too was living out the last years of his madcap life, and I hadn’t become fully aware of the post-apocalyptic authenticity morass which enveloped his later works and would impact me somehow.

The Dali Over-Licensing Debacle

By the time he died in January 1989, Dali’s estate was in full-blown disarray. In the final years, Dali had over-licensed himself, setting up the messiest, post-mortem artistic legacy of any artist of the last century. It seems that the aging Dalí and his wife willingly sold rights to virtually anything, including his signature for one-time cash payments, to fund their lavish lifestyle. After his death, his shady business managers sold even more additional rights. Thus, the art market was flooded with thousands of mass-produced “Dali’s,” which would, of course, totally dilute the brand.

Hundreds of artist’s proofs of late bronzes given to Dalí and his representatives as partial payment under the contracts, potentially worth millions if sold, remain unaccounted for. His licensees even managed to mass-“sign” 50,000 blank sheets which, fortunately, the US Postal Service in New York impounded before full-scale damage was further inflicted on the Dali brand.

But the fallout from over-proliferation of signed-Dali works was so widespread that a mini-industry of at least two competing Dali “expert-authenticators” in the US sprang up. Each of these “authenticators” (one in Santa Fe, New Mexico, the other in San Juan Capistrano, California, who bad-mouthed each other) charged from $200 to 300 just to certify your doubtful Dali print as “authentic.”

What a legal and artistic mess the Dali “deluge” had become. Did I pick a doozie or what? Did the one “serious” art purchase that I made, turn out to be a flop? Of course, in the back of my mind I was always mindful of the intrinsic market value of the piece. But was I, who prided myself in having a sharp eye, conned by a scam I hadn’t seen coming?

So many stories and images of famous fake art purchases flashed through my mind. Just recently, a whole hoard of 1,300+ fake Giacometti sculptures was found. And the one that cut too close for comfort was Imelda Marcos’ dubious purchase of a painting she still claims is by “Michaelangelo,” among a few others.

The Dubious Imeldific “Michaelangelo”

In her high-flying days, Mrs. Marcos had purchased Madonna and Child, purportedly by Michaelangelo, in 1983 from a certain Mario Bellini, one of her so-called “Italian connections,” for $3.5 million. Because she had a reputation for being greedy and gullible, Bellini knew she would never subject the work or its provenance to a rigorous and professional vetting process for authenticity; he demanded and got a cash deal. After receiving some negative feedback, Imelda quickly developed buyer’s remorse and, within days after the purchase, contacted two top New York law firms to see if she could recover “her”-- rather, the Filipino people’s--money, from the sale.

But she was quickly advised that since the purchase was made outside the US, and that she had signed a deed of sale with the caveat emptor (“as is”) clause accepted, she had little legal ground to stand on for recovering the money. Left with no other recourse, she ate humble pie and cut her losses quickly, realizing afterwards that she could possibly have been duped by one of her “favorite Italians.” But, of course, the $200 I paid for my Dali print came from my own honest sweat whereas Imelda’s easy $3.5 million outlay came from, well, the backs of millions of poor Filipinos.

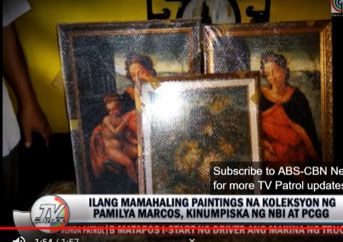

Imelda’s malfeasance in art matters did not end there. Either as part of her fantasy world, or in very shrewd anticipation of the day when the wolf would come a-calling at her door, Imelda had multiple copies of her most precious paintings made, including the Michaelangelo, and the originals were secreted somewhere else. Just this past November, Mrs. Marcos was convicted (once again!) by an anti-graft court in Manila.

As part of the Marcoses’ continuing efforts to thumb their noses at Philippine and international law, the bait-and-switch ploy with the paintings was, of course, used to further thwart the Presidential Commission on Good Government (PCGG). Carbon-dating oil masterpieces is quite expensive, and as of a few years ago, the Marcoses knew that (Noynoy Aquino’s) government at thae time, would not invest further resources in trying to authentic her art assets confiscated in the raids of September 2014. It was just another day in the Marcoses’ 50-year playbook of sticking it to their poor, unsuspecting countrymen each chance they got.)

A screen-grab of the 3 copies of the “Madonna and Child,” formerly owned by Imelda Marcos, during the confiscation raid of the Marcos home in San Juan in September, 2014. (From an ABS-CBN news report.)

Anyway, because of the larger horror story of Dali works’ widespread fakery, I put the issue of my print’s provenance out of mind and relegated it to the “I-don’t-want-to-deal-with-it-today” background, as if not thinking about it would magically fix the problem. For the longest time, I was in denial over the matter. There was this dreaded feeling that I might have bought a fake and was about to learn an expensive lesson of a lifetime.

2017 Visit to Northern Spain

In the meantime, an opportunity to visit northern Spain presented itself in 2017. The trip would encompass Catalunya, where the bulls ran in Pamplona, and Basque food was the most in-cuisine of the moment. It also gave me a chance to revisit Barcelona and see more of the vibrant city that I hadn’t done in the brief time I was there for the 1992 Olympic Games. And very possibly, if the logistics worked out, a trip to the old Del Fiero (my paternal clan) hearth in Vigo, Galicia.

As events turned out, former high school classmates Joe Santos and Ben Tuason and I spent our first free Sunday going to “mad” Señor Dali’s hometown of Figeres and his museum there. At about the same time, Dali was in the headlines again because a Spanish court had ordered the exhumation of his remains (from his crypt in Figeres) to resolve the paternity case of one Pilar Abel who claimed to be his daughter. Coincidentally, Abel was from the other city we visited that day—medieval Girona, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Here are some of the images from the Salvador Dali Museum in Figeres, Spain:

The whimsical outside walls.

The Courtyard/Atrium of the museum. (Photo courtesy of Myles Garcia)

The Mae West room.

With fellow Spain 2017 travelers: left-to-right: Ben Tuason, Shauna Santos-Peterson, Joe Santos and the author, at the back entrance of the Dali Museum in Figeres, Spain, September 2017.

It was a marvelous, edifying vacation. (The DNA test proved Ms. Abel not to be a love child of the maestro,so his remains were returned to the crypt.)

When I got back home to the US, I was going to face my Dali demons. Some 44 years had passed since I purchased the damned print. I was going to find out if I had the real thing or a dud. While, of course, it was not something that could be sold under the auspices of Sotheby’s or Christie’s, there were two smaller, more localized auction houses in the San Francisco East Bay where this would be a better fit.

On one of the Free Appraisal days, I took it in to one of them. When I had initially purchased the print in 1974, I was told it was part of the “Diana Suite.” Now came the moment of truth: was it a real, true-blue Salvador Dali or a real fake Salvador Dali?

The appraiser, Elly, pulled out her copy of the catalogue raisonné (the often-unimpeachable bible and resource of all the known and accepted authentic works by a particular artist) of Salvador Dali’s prints. There were so many prints and the book had no Index. So, we had to scour every page until she found it. There it was.

It Was Venus All the Time!

A few significant things were revealed.

One, it was not from a “Diana Suite” but from the Venus aux Fourrures (“Venus in Furs”) suite, a series made in 1969. This was the important; so when I purchased it in 1974, it was only about five years old.

My ink-and-charcoal etching of La Botte Violette, La Venus Aux Fourrures suite (#39 of a run of 50) by Salvador Dali, 1969.

I had heard of a Venus in Furs previously as an off-Broadway play, with kinky overtones.

Two, on my further research, the root material turned out to be a novella, Venus in Furs, by Austrian writer Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, first published in 1870. With a subtitle The Most Celebrated Masochistic Story Ever Written, well, that tells you all about the tale. Dali was no stranger to the kinkier realms of sexual activity as manifested by many of his works.

Three, in 2010 a play called Venus in Fur by David Ives, premiered off-Broadway with the Classic Stage Company of New York City. In 2013, Roman Polanski directed a French-language film version (La Vénus à la Fourrures) of the Ives play, and it won Polanski a 2014 Best Director Cesar—the French equivalent of the Oscars.

So, my particular print sub-species turned out to be La Botte Violette (The Violet Boot). We had also now traced a provenance. Even though the appraiser would have to do a little more research since the stratification of this particular suite/series was somewhat complicated, she was pretty sure it was a bona fide Dali. (She would not let me look at the catalogue raisonné for too long.) She would conduct more detailed research if I would consign it with them.

Of course, my first reaction was one of relief. Seemingly, it was genuine. But a little voice in the back of my head told me to still be cautious.

Eureka! Timeline-Chronology Was Key

But driving home that day, I had a eureka moment. I realized that because I had purchased the print in the winter of 1974, then it was an authentic Salvador Dali print. I had acquired it before the whole over-licensing scandal broke; thus, I was home safe! Why did I not think of this simple chronology before? All these years I had been unduly worrying turned out to be for nothing. So, indeed I did not own a fake Salvador Dali, but an authentic one.

After thinking about it shortly, I consigned the print for auction along with a pair of heirloom 24-carat Filipino-Spanish gold coin-cufflinks from my grandfather. While it was one of the handful of heirlooms passed down from my father, who and how often does one wear cufflinks these days? Also, they were really difficult ones to put on and were only sitting in a box in my bureau. With gold fetching a pretty high price it was time to sell. They didn’t do well at all when I posted them on eBay, being one of thousands of cufflinks for sale online. So, I thought I might as well try with the auction house, and collectively, both items put me over the minimum value threshold of the auctioneer.

A pair of 24-ct one peso Filipino-Spanish gold coins (center), minted in Manila in 1861, and turned into a pair of men’s cufflinks in 1927. The nubs are made of brass. (Photo, author’s collection.)

Post-Thanksgiving, the results came in. They both did well—even after minus the auction house’s 25 percent cut. The cufflinks made me more than what a jeweler had appraised them for, just strictly for the gold content. Dali’s print yielded me 300 percent of my original $210 investment in 1974 dollars; not anywhere near the recent, gut-busting $450 million(!) record sale for Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi painting but I still took it.

And that’s how Salvador Dali, the goddess Venus and I crossed paths on some metaphysical plain. When buying fine art, remember the old, fast-and-true maxim: buy art that really stirs your soul, and any monetary “windfall” will just fall into place.

SOURCES:

http://www.artnews.com/2008/12/01/the-dali%C2%AD-sculpture-mess/

http://archive.boston.com/bostonglobe/ideas/brainiac/2012/12/the_real_dali_d.html

“Thirty Years Later. . . Catching Up with the Marcos-Era Crimes,” by Myles A. Garcia, MAG Publishing, Hayward, CA, © 2016, p. 80

Myles A. Garcia is a Correspondent and regular contributor to www.positivelyfilipino.com. His newest book, “Of Adobe, Apple Pie, and Schnitzel With Noodles – An Anthology of Essays on the Filipino-American Experience and Some. . .”, features the best and brightest of the articles Myles has written thus far for this publication. The book is presently available on amazon.com (Australia, USA, Canada, Europe, and the UK).

Myles’ two other books are: Secrets of the Olympic Ceremonies (latest edition, 2016); and Thirty Years Later. . . Catching Up with the Marcos-Era Crimes published last year, also available from amazon.com.

Myles is also a member of the International Society of Olympic Historians (ISOH) for whose Journal he has had two articles published; a third one on the story of the Rio 2016 cauldrons, will appear in this month’s issue -- not available on amazon.

Finally, Myles has also completed his first full-length stage play, “23 Renoirs, 12 Picassos, . . . one Domenica”, which was given its first successful fully Staged Reading by the Playwright Center of San Francisco. The play is now available for professional production, and hopefully, a world premiere on the SF Bay Area stages.

For any enquiries on the above: contact razor323@gmail.com

More articles by Myles A. Garcia