From Colony to Campus: Filipino Pensionados in California, 1903–1940

/The first 100 Pensionados at the St. Louis Fair, 1904 (Source: Wikipedia)

Unlike thousands of Asian laborers who had entered California’s ports before them, these youths did not arrive to work in laundries, fields, or railroad gangs. They arrived as students—scholars of empire—sent by the Philippine Commission to absorb American knowledge and return as the vanguard of colonial modernization.

The Philippine Commission passed the Pensionado Act on August 26, 1903, creating the first U.S.-sponsored scholarship program in an overseas territory. The legislation funded the education of selected Filipino students in the United States so they could return better prepared to discharge civic duties and assist in colonial administration. Commissioner William Howard Taft, the first Civil Governor of the Philippines, explained the goal as training “a body of young men, educated in our institutions, who shall become the apostles of American ideals in their own land.” For the students, the opportunity promised adventure, prestige, and the chance to elevate both their families and their nation.

The San Francisco Chronicle devoted a full column to their arrival, describing the students as “the first fruit of benevolent assimilation.” The paper marveled at their attire, remarking that “the brown-skinned youths, clad in black coats and polished shoes, looked more like delegates to a convention than arrivals from a distant archipelago.” The San Francisco Call echoed this impression, calling the group “the living proof that the Philippines is a land of promise, sending forth sons eager to learn the ways of liberty.” Such headlines reassured local readers that America’s war in the islands—barely concluded after years of bloody insurgency—had been worthwhile.

Photographs circulating in Bay Area newspapers captured the students standing stiffly on deck, their faces caught between pride and apprehension. Some carried English-language primers, while others clutched satchels supplied by the Insular Bureau. One reporter remarked on the solemnity of their procession down the gangplank: “They walked two by two, as if already in some kind of ceremony, watched by Americans who whispered, ‘These are our pupils from the Orient.’” For many Californians, this marked their first encounter with Filipinos who were not laborers. The state knew Chinese laundrymen and cooks, Japanese farmers, and South Asian field hands. Filipinos—especially elites—remained largely unfamiliar.

As one local columnist explained, “These are not coolies but scholars, not peasants but pensionados.” This distinction, eagerly repeated by the press, foreshadowed the unique role pensionados would play as symbols of a “different” kind of Asian—one portrayed as malleable to American culture, though never quite equal.

U.S. and Philippine officials carefully orchestrated the students’ landing. Representatives of the Bureau of Insular Affairs greeted them at the docks, along with educators responsible for guiding their orientation. Captain John R. M. Taylor, a U.S. Army officer who had served in the islands, declared: “These young men carry the hope of their country. We shall watch their progress closely, for their success is the success of our policy.”

Students and Political Instruments

From the moment they set foot in California, the pensionados became both students and political instruments. Officials did not send them immediately to universities. Instead, they believed the students required a period of acculturation in high schools and preparatory academies. This decision reflected both pedagogical caution and racial prejudice. Educators doubted whether Filipinos, even those selected through competitive examinations, could thrive right away in American universities. Authorities scattered the first pensionados across California—Santa Paula, Los Angeles, Berkeley, Oakland, and San Francisco—so they would immerse themselves in English, American history, and civic culture.

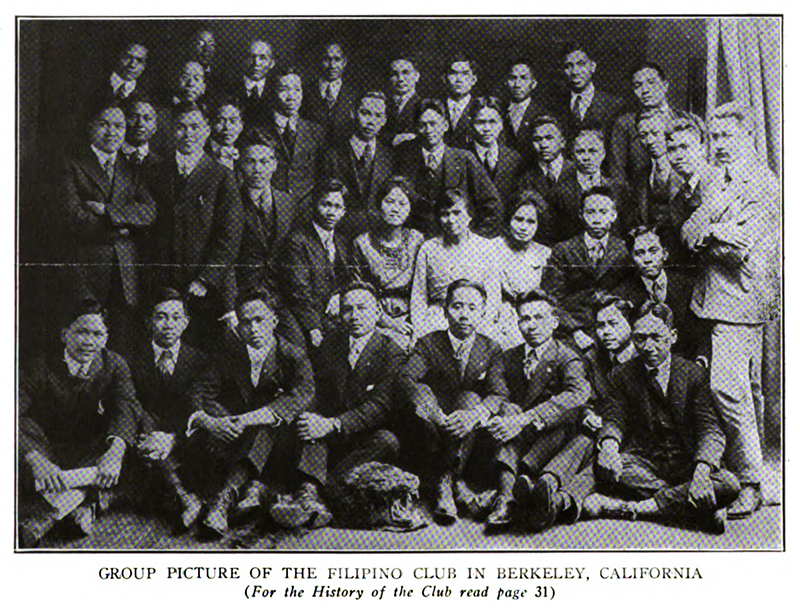

Filipino Club of Berkeley (Source: Geronimocristobal.com)

Accounts of the voyage survive in letters published in Manila newspapers. José Abad Santos, who later became Chief Justice of the Philippines, wrote home: “We spent our days on the ship reading and practicing our English. Some of the Americans on board were curious about us, asking endless questions about the Philippines. We answered as best we could, already feeling the weight of being representatives of our land.” Another student, writing anonymously to El Renacimiento, confessed that seasickness and homesickness competed with excitement: “As we watched the islands fade from view, I wondered if we would return as strangers to our own people.”

The voyage also introduced them to racial hierarchies of trans-Pacific travel. While American passengers dined in the ship’s main salons, stewards often relegated the pensionados to separate tables. One student later recalled: “We were well treated but always reminded that we were not quite their equals.” These experiences foreshadowed contradictions they would face on land: celebrated as symbols, yet marginalized as individuals.

Local Californians greeted them with curiosity, admiration, and paternalism. The Santa Paula Chronicle announced the arrival of Timoteo Abaya, who would enroll at the local high school. “Our town has been honored with the charge of one of the Filipino scholars,” the paper declared. “We shall endeavor to Americanize him thoroughly.” Church groups organized teas and socials to welcome the pensionados, while civic clubs sought opportunities to hear them speak about their homeland.

Teachers, interviewed by newspapers, expressed cautious optimism. One Oakland educator commented: “They are bright lads, industrious, and eager to please. Their English is already better than we expected, though they must unlearn many errors. With discipline, they shall make fine scholars.” Another teacher, less charitable, told the Berkeley Gazette: “They are polite, yes, but they carry an Oriental reserve. It will take time to instill in them the frankness of American youth.” Such statements revealed the racialized expectations that shaped their reception.

Burden of Exemplars

From the beginning, pensionados bore the burden of exemplars. Observers scrutinized their every action as a measure of American colonial success. A San Francisco Examiner editorial put it bluntly: “The eyes of two nations are upon these boys. If they succeed, America is justified; if they fail, America is shamed.” This immense pressure meant missteps were rarely tolerated. Students who struggled academically or socially risked being labeled as evidence of Filipino incapacity rather than as individuals adjusting to new circumstances. One pensionado confided in a letter home: “We feel as if we must always be on display, even when walking to school. The newspapers speak of us as if we are already men of consequence, but we are still boys, learning our way.”

Their colonial status meant they could never be simply students; observers constantly reminded them of their symbolic role. The pensionados’ arrival in San Francisco in 1903 represented more than a routine immigrant landing. It was a staged event, freighted with imperial significance. Newspapers hailed them as proof of benevolent assimilation. Teachers and officials prepared to mold them into Americanized leaders. Californians regarded them with curiosity laced with condescension. For the students, the moment marked both a beginning and a burden: a new life in a strange land, under constant scrutiny, charged with representing not only themselves but an entire colonized nation.

First Pensionado women in 1906 (Source: The Filipino/msu.edu)

Once the first group of pensionados disembarked in San Francisco, officials quickly dispersed them across California. American administrators insisted that before entering universities, the young men must undergo an “orientation” period in secondary schools and preparatory academies. This requirement was not merely a matter of pedagogy—it reflected doubts, rooted in racial prejudice, about whether Filipinos could handle university-level work without first immersing themselves in the American classroom. California high schools thus became the first laboratories of the pensionado experiment.

Officials placed students deliberately. Some went to small agricultural towns like Santa Paula in Ventura County, where supervisors could closely monitor their progress. Others enrolled in city schools in Los Angeles, Berkeley, Oakland, and San Francisco. The Santa Paula Chronicle proudly told its readers in November 1903 that “our community has been honored with the education of one of the Filipino pensionados, a bright lad named Timoteo Abaya.” By scattering the students, authorities hoped to prevent them from clustering together and speaking native languages. Instead, they wanted them immersed in English and American social life.

At Los Angeles High School, pensionados quickly drew attention. The Los Angeles Times described them as “serious young men, polite and industrious, who already show the fruits of discipline.” In Berkeley and Oakland, pensionados entered academically rigorous programs. A teacher at Oakland High told the Oakland Tribune: “They are quick to learn, though they carry with them a kind of reserve. They are not boisterous like our American boys.”

The colonial narrative cast them simultaneously as proof of progress and reminders of supposed backwardness.

Opportunities and Alienation

Classrooms revealed both opportunities and alienation. Teachers admired the students’ diligence. In 1904, the Berkeley High School Gazette observed: “Our Filipino students astonish with their grammar and composition, surpassing even some of our native-born classmates.” Yet the same article exoticized them as “dark-skinned youths whose manners are quaint but charming.” Praise almost always carried a paternalistic edge.

Individual teachers varied in their reactions. Some expressed genuine admiration. Miss Alice Butterfield of Santa Paula High told a reporter, “Timoteo is a most diligent boy. He rises early, studies late, and shows gratitude for every kindness. If all our American pupils had such industry, our schools would be better for it.” Others displayed racial condescension. A Berkeley teacher remarked: “Their minds are quick, but they must abandon their Oriental reserve and learn the frankness of American life.”

For the pensionados themselves, adjustment often proved difficult. Letters sent home to Manila described bewilderment at American customs. One student wrote: “We are made to drink cold milk at breakfast, and butter is spread on bread as if it were cheese. It is strange to us.” Another noted classroom culture: “Here the students question the teacher boldly, even argue with him. In Manila we were taught to listen in silence. It feels both liberating and improper.”

Despite praise in the press, pensionados still encountered California’s racial hierarchies. In Los Angeles and Oakland, people in the streets sometimes mistook them for Chinese or Japanese and hurled slurs. A student complained in a letter to La Democracia: “We are called ‘Japs’ by the boys in the street, and though we protest we are Filipinos, they laugh and say it is all the same.”

Government sponsorship shielded them from some of the harsher discrimination aimed at other Asians. In April 1904, the San Francisco Call ran a feature contrasting pensionados with Chinese laundrymen and Japanese farm workers: “These Filipinos carry books instead of brooms. Their destiny is not in menial labor but in the service of their people under America’s guidance.” Such comparisons reinforced stereotypes that divided Asian communities, casting Filipinos—at least the elite few—as more assimilable.

Local communities often treated the pensionados as curiosities. In Santa Paula, society pages reported their attendance at church. “The young men from the Philippines were present at Sunday service and sang from the hymnal with vigor, their accents charming the congregation.” In civic events, they were sometimes asked to describe their homeland. A pensionado in Los Angeles received an invitation to a Chamber of Commerce luncheon, where he politely explained the geography of Luzon and Mindanao to a curious audience. Yet these occasions could be uncomfortable. One pensionado confessed in a letter: “They ask us if we live in huts of bamboo, if we have ever seen shoes before coming here. We smile and answer, but inside we burn with shame that they think us savages.”

The colonial narrative cast them simultaneously as proof of progress and reminders of supposed backwardness. Public ceremonies amplified this dual role. At a Berkeley school assembly in 1904, a pensionado gave a speech thanking the U.S. government for the opportunity to study. The Berkeley Gazette reported: “The audience was deeply impressed by his eloquence and poise, remarkable for one so young.” Behind the praise, observers knew this display served an imperial purpose: the students’ performance symbolized both the success of benevolent assimilation and the pliability of colonial subjects.

For pensionados themselves, the personal costs remained heavy. They had spent formative years in the United States, adopting American habits of thought and speech. Some returned home feeling estranged from their own communities. A Stanford-trained lawyer admitted in 1920: “Our people see us as too American; Americans still see us as too Filipino. We belong fully to neither world.” Others embraced their hybrid identity. Camilo Osías argued in Manila that pensionados had become “bridges between East and West, interpreters of two civilizations.” For him and others, American training was not simply an imposition but also a tool to advance Filipino aspirations, including the independence movement that grew in the 1920s and 1930s.

Camilo Osias (Source: Pinterest)

Paradoxes of Empire

The pensionado story embodied the paradoxes of empire. Officials educated them to serve colonial administration, but the students also acquired the intellectual tools to critique colonialism itself. Californians celebrated them as model students while ignoring the racism they endured. They stood as exemplars to their fellow Filipinos but often felt alienated from them. They lived as a generation caught between admiration and alienation, loyalty and independence, gratitude and resentment. One pensionado wrote late in life: “We were sent to be made into Americans, but we became Filipinos in a new way. We saw liberty, we saw hypocrisy, and we resolved to make our own nation worthy of respect.”

When the first pensionados stepped onto San Francisco’s piers in 1903, few could have predicted how long their shadows would stretch. Though fewer than 500 students participated in the program over its lifespan, their presence in California left enduring marks on both American and Philippine history. Their story was not only about young men adapting to new schools and unfamiliar customs; it was also about a generation charged with proving the success of an empire while quietly carrying the seeds of its undoing.

In the Philippines, the return of pensionados coincided with the gradual expansion of Filipino participation in government. By the 1910s and 1920s, many former pensionados held positions as lawyers, judges, engineers, and professors. Some became legislators, such as Camilo Osías, who not only sat in the Philippine Assembly but also served as Resident Commissioner to the U.S. Congress, lobbying for greater autonomy. Jorge Bocobo became president of the University of the Philippines. José Abad Santos rose to Chief Justice, later martyred under Japanese occupation. Vicente Lim, who had begun his studies in California before West Point, became the Philippines’ first Filipino West Point graduate and a general celebrated for his defense of Bataan.

Jorge Bocobo (Source: Wikipedia)

By the 1930s, their influence was unmistakable. Many of the framers of the 1935 Philippine Constitution had once sat in California classrooms. American newspapers that had once photographed them in school assemblies no longer paid attention, but in Manila their names carried great weight. They embodied both the success and the limits of America’s colonial project: trained to administer empire, they often became advocates for independence.

Vicente Lim at West Point

Not all returned triumphantly. Some found that their American education left them feeling estranged at home. One pensionado recalled in a 1930 interview: “We came home with American habits, but our people saw us as too foreign. At the same time, Americans still saw us as natives. We belonged to neither world.” For others, however, the dissonance produced new energy. California had given them not just technical training but also exposure to liberal ideals, civic rhetoric, and democratic debate. They used those tools to challenge the very subordination they had once been sent to uphold.

Hybridity Shaped Politics

This hybridity shaped Philippine politics. Pensionados brought back both technical expertise and a sharpened awareness of the contradictions of American rule. They had been praised in California as symbols of progress while enduring the sting of racism in streets and shops. Those experiences left many determined to claim dignity and autonomy for their people.

In California, the pensionados were remembered in limited ways. University alumni bulletins occasionally recalled them as “earnest foreign students who studied diligently and returned to their islands.” For Californians in the 1920s and 1930s, they provided a convenient contrast to the growing number of Filipino laborers in fields and canneries. Newspapers invoked pensionados as proof that “the right kind of Filipino” could be educated, while disparaging the manongs as undesirable. Among later Filipino students, however, pensionados stood as trailblazers. By the 1920s, self-supporting Filipino undergraduates entered Berkeley, Stanford, and UCLA. Some cited the pensionados as inspiration, proof that Filipinos could succeed in American classrooms. A Berkeley student in 1926 explained: “We walk in the footsteps of those pensionados, though without stipends we scrub floors by night to pay tuition.” Their example widened the horizon of possibility, even if the privileges of stipends and supervision were no longer available.

Over time, the memory of the pensionados blurred into broader Filipino American history. By the 1930s, the dominant image of Filipinos in California was the manong—the field worker, the bachelor, the union organizer. In Manila, pensionados were remembered as nation-builders; in California, they faded into faint shadows, overshadowed by the mass migration of their countrymen. Yet the contrast proved instructive. Pensionados and manongs represented two faces of the Filipino diaspora: elite scholars in lecture halls and migrant workers in fields. Together they embodied the breadth of Filipino experience under empire. Both confronted racism. Both forged paths of survival. Both left legacies that shaped Filipino identity in America.

World War II tested the generation’s resilience. Many pensionados rose to leadership in wartime government and resistance. Vicente Lim was executed by the Japanese for refusing to collaborate. José Abad Santos died as a martyr, refusing to abandon his loyalty to the Commonwealth. Their American training, once intended to serve colonial administration, became tools for defending sovereignty.

Jose Abad Santos (Source: Wikipedia)

Celebrated as Pioneers

After independence in 1946, the Philippine government celebrated pensionados as pioneers. Officials occasionally invoked their legacy when sponsoring new waves of scholars abroad. In California, Filipino American organizations remembered them as the first Filipinos to prove their ability in U.S. universities. Their lives bridged colonial tutelage and national independence.

The pensionados carried burdens far greater than any syllabus. They had to prove that Filipinos could master Western knowledge, embody gratitude for America’s “benevolent assimilation,” and return as advertisements of empire. Many succeeded brilliantly, but success was never simple. They endured prejudice, loneliness, and the strain of representing a nation under colonial rule. Their story underscores that education is never neutral. In the pensionado experiment, classrooms became instruments of empire but also crucibles of resistance. California gave them textbooks and laboratories, but it also taught them sharp lessons about conditional equality. From those contradictions, they forged hybrid identities—part American, part Filipino, wholly their own—that helped shape a nation.

Today, traces of their presence linger in archives, yearbooks, and yellowing newspapers. California remembers them faintly, while the Philippines honors them as pioneers. They were the first official Filipino students in America. Small in number, they left a legacy far larger than their size: a generation that carried their people’s hopes across the Pacific and returned to demand a future beyond colonial rule.

Alex S. Fabros, Jr. is a retired Philippine American Military History professor.

More articles from Alex Fabros, Jr.