Comedian Allan Manalo’a Life "In Bituin"

/Allan Samson Manalo with a framed photo of the late Joyce Juan Manalo. Photo by Wilfred Galila

“What keeps me going is to look at her departure as being on the other side of the veil. She’s still with me, but she’s just in another form of energy. I can’t touch her, I can't have that human feel, it’s not tactile anymore but I still feel her.”

It has been two years since Joyce Juan Manalo passed away after a battle with cancer. It is said that “time heals all wounds,” but the timeframe is not specified, and grief is in the heart of the bereaved. Allan is still living with grief.

“It’s OK not to be OK. It’s OK that you can take your time. Grief is something not to get over, it’s something you learn to live with. Grief is love rearranged. It’s the other side of the coin of that love, that intensity. The stronger the intensity of that love, the stronger your grief will be.”

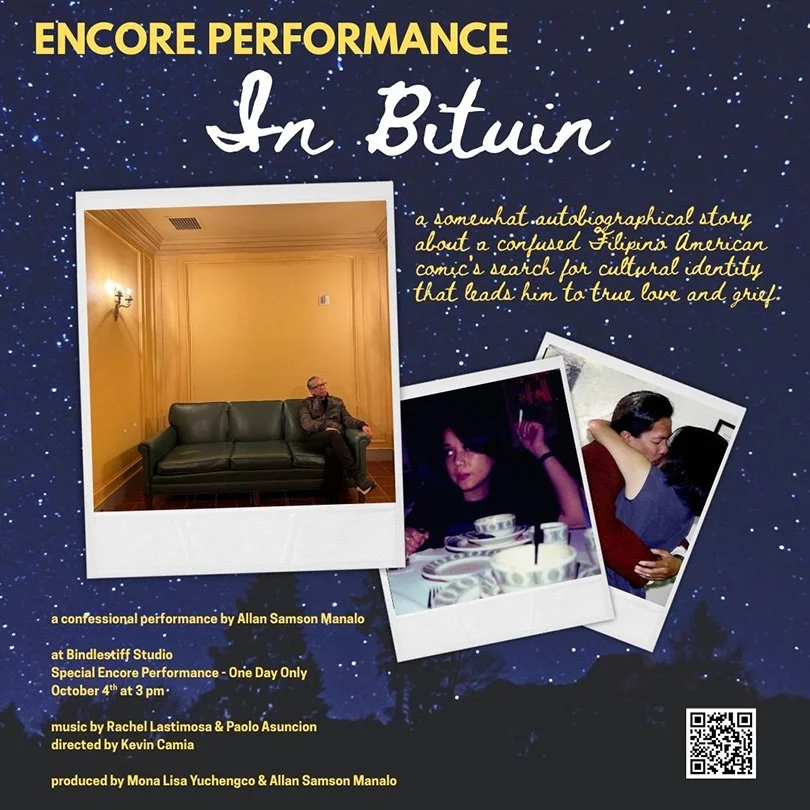

He channels the intensity of his enduring grief into his one-man show, In Bituin, slated for a special one-day only encore show on October 4, 2025 at Bindlestiff Studio, an apt venue that is close to Allan’s heart. Along with Joyce, Allan ushered Bindlestiff Studio to become what is now known as “The Epicenter of Filipino American Performing Arts.”

A Play on the Phrase

The title In Bituin is a play on the phrase “in-between” and the Filipino word bituin (star), symbolizing both the space between cultural identities and the transformative power of enduring grief. A confessional performance directed by Kevin Camia, with music by Rachel Lastimosa and Paolo Asuncion, In Bituin premiered at Bindlestiff Studio in May 2025.

Experiencing In Bituin is a deeply empathetic and vicarious journey through Allan’s semi-autobiographical story—intimately told through photos, video, and punctuated by live music. Immersed in the narrative, Allan surrendered himself fully to the telling.

“I went off script and I dropped everything I wrote; I just went off the path and just told the story. But I had some really good tech people who knew kind of like what I was trying to do.”

Allan Samson Manalo in front of Bindlestiff Studio. Photo by Wilfred Galila

This sets the stage for a raw, unguarded performance of fearless vulnerability that earns your full trust and attention. Allan becomes like a close friend, even if you’ve never personally known him, and his story becomes your own—Allan’s search for cultural identity, finding the love of his life, and losing her 29 years later. You laugh, you cry. You feel the joy and warmth, as well as the pain and sorrow that life, and ultimately death, bring. It is cathartic: a masterclass in communal grieving.

You might wonder how comedy and tragedy can combine in In Bituin, but it turns out that tragedy is precisely what fuels the comedy.

“The crux of stand-up comedy comes from tragedy, comes from pain, and how you deal with that pain. The frustration of having to deal with certain things, the mundane things in life, why are things this way?’ All these kinds of different things that the powers that be try to dictate to you and you having to maneuver that.”

On teaching stand-up comedy, Allan says: “One of my rules is don’t try to be funny on stage,”. “What we want to see is the world according to you and your point of view, because eventually people will come to see you, not necessarily your jokes, but you and what you have to say about things.”

Humor as a Tool

He explains how humor as a tool works. “Comedy is really about tension and release. So, you’re creating this heavy tension and then, boom, you do something that takes it to the other direction. That’s where the release gives people permission to laugh about this.”

Growing up in Seaside, Monterey County, Allan considered himself the opposite of funny. In fact, he was very shy. But he also liked girls. “I read this article that said that the number one thing that girls like is a guy with a sense of humor.”

When he was 14, he was introduced to stand-up comedy by his best friend who was a big fan of Richard Pryor. “We’d go over to his house, and he would play Richard Pryor albums. I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, this is so hilarious.’”

That started him listening to stand-up comedy. He became a fan of Richard Pryor, George Carlin, Steve Martin, Flip Wilson, Dick Gregory–and Eddy Murphy, who made him, at 17, think about doing stand-up comedy himself. “I would play Eddie Murphy, and I would recite his bits and, sure enough, I was getting dates, the girls were laughing and they thought it was funny. After that, I had a fascination about trying to make people laugh and, you know, it worked.”

A girlfriend from Hawaii played him a record of Andy Bumatai, a stand-up comedian who is part Filipino. “It was the first time I heard somebody talk about being part Filipino. That perked my interest.” He then saw Bumatai, “a superstar in Hawaii,” perform in person. “I was like, ‘Oh, I want to start doing that.’”

Allan eventually moved to San Francisco. “I didn’t know it was a comedy town.” He saw an ad for stand-up comedy classes at Holy City Zoo, a comedy club on Clement Street where the likes of Robin Williams and Dana Carvey performed. “I didn't know it was a legendary comedy club at the time.”

He took classes at Holy City Zoo under John Cantu and learned a lot about stand-up. “I started watching more comics and I became a really hardcore fan of standup comedy. I followed everybody I could, I was just really consuming it, read all the books I can, and really got into it.”

“Grief is something not to get over, it’s something you learn to live with. Grief is love rearranged.”

His First Time

The first time Allan did a stand-up set was at the Holy City Zoo. “In my college days when I was in Hawaii, I would make people laugh. That was my first time tasting the idea of making a lot of people laugh. But it wasn’t until I got to the Holy City Zoo that I started doing stand up and I got some laughs.”

Allan became a regular performer at Holy City Zoo and The Rose and Thistle, another legendary comedy club on California Street, where he got booked after doing an open mic set. Eventually he performed at Punch Line. He met other stand-up comics such as Margaret Cho, Mark Curry, Wiley Roberts, Patton Oswalt, and Marc Maron. “I got to pick their brains and really talk to them about the business.”

In 1993, Allan received an offer to go on the road for a college tour. “I wanted to really experience how it would be like to do stand up on a college circuit. It was tough. I really learned a lot.”

At the same time, he was starting to question what it meant to be Filipino American and began incorporating his identity into his comedy routine. “I started to really get more traction in getting booked when I started talking about my identity, my cultural identity, and my search for it.”

Search for Identity

Allan grew up in a predominantly Black neighborhood in Seaside, Monterey County. His classmates and friends were Black and he wanted to be Black. “I wanted to be cool. I wanted to be accepted. And all of Monterey is pretty white. Well, it's Monterey, see?”

There were also a lot of Filipinos where he lived, but he did not identify with them at the time. This was before he knew what cultural identity was. “I really didn't see myself as the cool culture at that time. I'm a Filipino kid in search of his own cultural identity but not realizing it’s right there in front of me.”

From Seaside, Allan moved to Alameda, then to Vallejo, then to San Diego where in high school he fell in love with a Chicana and wanted to be a Cholo. “It really was my first time being in love. I got into that culture because there are so many parallels to the Filipino culture.”

From San Diego, he went to college in Hawaii, where there were more Filipinos, but he still hadn’t fully grasped what it means to be Filipino American. “Because my idea of Filipino was Filipinos from the Philippines, not necessarily the Filipino American concept.”

It was not until he lived in San Francisco and went to San Francisco State University that his Filipino American culture and heritage became clear to him.

“I took my first Asian American Studies class with Dan Gonzalez. I’m learned about our history here and our contributions to this country and our stake in this country. Going through that was just mind blowing. It was an eye-opening experience for me where I learned to have pride in my Filipino American heritage. I realized, oh my God, all this time I've been living this life where I grew up in this Filipino American culture. I was always immersed in it and didn’t know it.”

First Trip to PH

After being on the road doing stand-up for two years, Allan got a call from his mother. “‘Hey, we’re going to the Philippines. Do you want to go?’” He had never been to the Philippines and he jumped at the opportunity.

“Going to the Philippines for the first time and really experiencing it was a revelation and a way to find out how American I really was. I was much more American than Filipino.” Allan searched for validation for his Filipino identity in his fateful first trip in 1995. In the process, he met the love of his life.

Allan landed in the Philippines in January 1995. About a week before his return flight to the United States, he went with his friend, Melvin Lee, a theater artist with the Philippine Educational Theater Association, to Blue Cafe, a gay bar in Malate where all the theater folks hung out. “I went and I saw Joyce from a distance. She was hanging out with her brother, and I thought it was her boyfriend.”

Allan was introduced to Joyce by another friend, but she was not that interested in him. “Shook my hand like it was a dirty panty, you know.”

Melvin asked Allan, “Do you see anybody that caught your eye?” Allan told Melvin about Joyce. “Melvin’s eyes really lit up and he told me, ‘You and Joyce are perfect for each other.’”

Melvin hosted a party called “The Lonely Hearts Club” and invited both Allan and Joyce. This time they hit it off right away.

Allan Samson Manalo and Joyce Juan Manalo poses in front of the original door of Bindlestiff Studio at its 30th anniversary celebration on December 7, 2019. Photo by Allan Samson Manalo.

Whirlwind Romance

After a whirlwind romance, Allan asked Joyce to come to San Francisco and bought her a one-way ticket. She arrived in April, and Allan proposed to her at the Golden Gate Bridge. They married on June 18, 1995 at 2:00 a.m. at City Hall on the old strip in Las Vegas since they could not find an Elvis Chapel that was open.

When Allan went to the Philippines in June 2025, in celebration of their 30th wedding anniversary, Joyce’s brother handed him pictures of their wedding night in Las Vegas that he thought had been lost. “I have a picture of the moment I kissed her, as in ‘You may kiss the bride’ moment. I'm adding that to the October show because I didn't have those pictures before.”

Part of their honeymoon was Joyce joining Allan on the road touring through 43 states and performing in over 400 colleges. Joyce performed as “Vanna Brown” in their touring game show called Blizzard of Bucks.

Allan and Joyce settled in San Francisco in 1996. He continued performing with his comedy troupe, Tongue in a Mood, which was steadily gaining popularity. In 1997, when the troupe needed a venue, Allan and Joyce attended Babae, a one-woman show by Lorna Aquino Chui (now Lorna Velasco), at a small black box theater on 6th Street called Bindlestiff Studio. It was exactly the space they had been searching for. By spring 1998, Allan and Joyce had taken over the operations of Bindlestiff Studio, transforming it into the cultural epicenter for Filipino American performing arts in the Bay Area.

They became beloved and prominent members, contributing to and serving the Filipino community in the South of Market, now known as SOMA Pilipinas, the Filipino Cultural Heritage District. As the years went by, Allan set aside his career as a stand-up comic.

A Career Set Aside

“I had shelved it for a long time, almost ten years. I just was focusing on making money and supporting us and that kind of thing.”

But Joyce wanted Allan to get back to doing stand-up. “She said, ‘You should go back, you should start writing again. ‘That's how,’ she said, ‘I fell in love with you.’” At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, Allan started writing jokes again and would perform them on Zoom shows with Kevin Camia. He continued performing when pandemic restrictions began to ease and outdoor venues opened up. “Joyce was really happy when I started doing stand up again. By 2022, I was already getting booked.”

At the end of 2022, Joyce became ill. Allan stopped performing altogether and just focused on caring for Joyce until her death in July 17, 2023.

Three months after Joyce passed away, Allen went back on stage. He attended the graduation of Kevin Camia’s stand-up comedy class that he had helped out with. Kevin asked him if he wanted to do a set. “When I got up there, I really did not have something solid prepared. I just went up there and talked about what I was going through, and there were certain things that I already had worked out in my mind but I didn’t quite deliver it yet.”

Creating ‘In Bituin’

It was the beginning of his process of creating In Bituin. “There was no idea for the show yet. That was the genesis of it. When I went up there, a lot of it was riffing, just coming out and talking about crying and talking about the things people say to you. It was liberating because I’ve always wanted to be that honest in my stand up but I was too afraid to do anything like that. I always had my jokes prepared. It was the first time I went really inside, like a deep and honest and truthful inside. It wasn’t crafted. It was whatever came out, came out. But at the same time it was terrifying to be vulnerable. You could feel the energy in the room and the silence.”

Allan felt that it was something that Joyce wanted him to do. “To work through it, to put me back into my craft, and to really tell our story the way it was a love story. But I didn’t know that at first. I wasn’t sure how to frame it.”

Then things began to fall into place, and In Bituin finally came together. “I thought to myself, maybe I could just do all my old bits about my cultural identity, then I realized Joyce was a big part of that. She was a huge part of me finding that validation of being Pinoy that I've been looking for all my life. That’s it. That’s the show. I have to blend the two together.”

After seeing the world premiere performance of In Bituin last May, Mona Lisa Yuchengco, publisher, philanthropist, community activist, and filmmaker, approached Allan about the possibility of doing another show. “She said, ‘I want people to know about this kind of love story. And I want people to know about grief.’”

Ahead of the October 4 encore performance of In Bituin, I asked Allan where he was with his grief. He says that periods of sadness no longer come as often as they did. “They used to come every time. But there were times when I still feel the weight of it and start crying, and I know already that it helps to let it all out.”

Performing in Bituin placed Allan at a crossroads, reaffirming his commitment to stand-up comedy. It was the path Joyce had always wanted him to return to. “To share our love story with the hopes that it will really inspire people. It wasn’t all easy, of course. We had our arguments and all of that but the core love that was there from day one, that I felt when I fell in love with her first, that has never left. I think telling the story over and over again has made me realize that it’s stronger than ever. And one of my regrets is I wish I expressed more how much she meant to me when she was alive.”

In Bituin is Allan’s way of giving permission for people to “grieve in the way they want to grieve, and that there’s no time limit to it, that we’re all going through this process. Grief is not necessarily just about death. Grief is a loss of anything. There’s a lot of grief with what’s going on now in this world. It’s OK to deal with that in your own way and hope to find strength and gratitude out of it.”

Grief is transformative—a liminal space between the past and the life that must continue after loss.

“It is that in-between space, between what life used to be and what your life is going to be. You’re a caterpilar in a cocoon, and hope that you come out as a butterfly. It’s like the scab that finally comes off bit by bit. It becomes a scar that reminds you it’s still there. Your skin’s marked but you’re stronger for it.”

In Bituin. Encore performance. Written and performed by Allan Samson Manalo, Directed by Kevin Camia. Produced by Mona Lisa Yuchengco and Allan Samson Manalo, Music by Rachel Lastimosa and Paolo Asuncion.

October 4, 2025, 3:00 p.m. at Bindlestiff Studio, 185 6th St., San Francisco. www.bindlestiffstudio.com / Box Office: (415) 796-3848. Ticket Price: $25 advance, $30 at the door, $50 to support the artists (proceeds go to the Joyce Juan Manalo Legacy Fund)

Wilfred Galila is a San Francisco Bay Area-based multimedia artist and writer.

More articles from Wilfred Galila