Alice Roosevelt, the Sultan of Sulu, and the Theater of American Empire

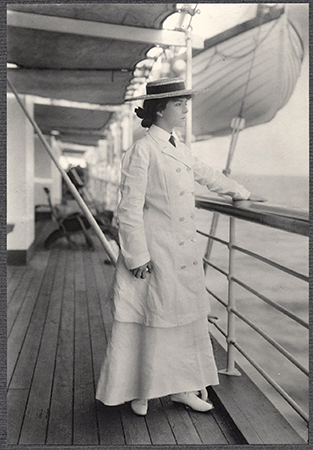

/Alice Roosevelt on the SS Manchuria

Her encounter with the Sultan of Sulu was brief, ceremonial, and carefully choreographed, yet it has endured as a revealing episode in the history of American colonial rule. The significance of the meeting lies not in its immediate political consequences, but in what it exposed about the nature of empire: how power was performed, how sovereignty was symbolically displaced, and how gender, spectacle, and celebrity were mobilized to legitimize imperial domination.

The Sultan who proposed marriage to Alice.

Alice Roosevelt Longworth was not a diplomat in a formal sense. She held no office, signed no treaties, and issued no proclamations. Yet by 1905, she was one of the most recognizable public figures in the United States. As the president’s eldest child, she embodied a new kind of American womanhood—confident, modern, outspoken, and highly visible in the public sphere. Her celebrity was cultivated by the press and carefully managed by political strategists who understood that her presence abroad could serve as soft power.

When Secretary of War William Howard Taft organized his inspection tour of American possessions and allied states in Asia, Alice Roosevelt’s inclusion was deliberate. Her journey was meant to signal that American expansion was not merely military or administrative, but also cultural and civilizational. Wherever she went, she drew crowds, headlines, and commentary. In the Philippines, her presence carried particular weight, as American officials sought to project an image of benevolent governance after years of brutal counterinsurgency during the Philippine-American War.

The Sultanate of Sulu occupied a unique position within this colonial landscape. Long before Spanish colonization, the Sultanate had been a powerful maritime state, controlling trade routes across the Sulu Sea and maintaining diplomatic relations with neighboring polities and European powers alike. Its authority rested not only on political control, but also on Islamic legitimacy, kinship networks, and regional influence extending into what are now Malaysia and Indonesia. Spanish efforts to subdue Sulu had been intermittent and largely unsuccessful, relying on treaties that recognized the Sultan’s autonomy in exchange for nominal allegiance. When the United States replaced Spain as the colonial power in 1898, it inherited not only territorial claims, but also a long history of negotiated sovereignty.

The American approach to Sulu in the early years of occupation was shaped by pragmatism. Confronted with ongoing resistance in Luzon and the Visayas, U.S. officials were reluctant to open another full-scale conflict in the south. The result was the Bates Treaty of 1899, which recognized the Sultan of Sulu's authority while asserting American sovereignty in principle. The treaty promised non-interference in religious practices and internal governance, while securing American strategic interests. Yet from the outset, the treaty was understood by American officials as temporary. It was a mechanism to buy time, not a commitment to long-term pluralism. By the early 1900s, the United States was steadily eroding the Sultanate’s autonomy through administrative reforms, military presence, and the redefinition of legal authority.

It was in this context of diminishing sovereignty that Alice Roosevelt met Sultan Jamalul Kiram II. By 1905, the Sultan’s power was already circumscribed. He retained ceremonial authority and symbolic prestige, but real control over territory, taxation, and armed force was slipping away. American officials, however, continued to stage encounters that suggested mutual respect and continuity. These performances were intended to smooth the transition from negotiated coexistence to administrative domination. The presence of Alice Roosevelt added a new dimension to this imperial theater. Her encounter with the Sultan was widely reported as evidence of American goodwill and cultural openness. Photographs, descriptions of attire, and accounts of polite exchange emphasized harmony rather than hierarchy.

Alice Roosevelt in Cebu

Yet the hierarchy was unmistakable. Alice Roosevelt represented the ruling power; the Sultan represented a polity in decline. The meeting was not between equals, but between a sovereign in fact and a sovereign in name only. The very informality of Alice Roosevelt’s role—her lack of official authority—underscored this imbalance. She could engage with the Sultan as a social equal precisely because the United States no longer regarded him as a political threat. Ceremony replaced negotiation; spectacle replaced diplomacy. What remained of Sulu sovereignty was folded into the aesthetics of empire.

Gender played a crucial role in this dynamic. Alice Roosevelt’s public persona challenged conventional expectations of women’s roles, yet her presence abroad reinforced imperial narratives rather than subverting them. As a young, confident American woman interacting with Asian rulers, she symbolized the moral and cultural authority of the United States. In the Muslim south, this symbolism carried additional weight. American colonial discourse frequently portrayed Moro societies as patriarchal, backward, and resistant to progress. Alice Roosevelt’s visibility allowed American officials to frame imperial rule as emancipatory, even as it imposed new forms of control. The spectacle of a Muslim ruler hosting the president’s daughter suggested acquiescence to a new order in which American norms—social, cultural, and political—were ascendant.

From the Sultan’s perspective, participation in such encounters was a matter of survival. Refusal would have invited retaliation; compliance, at least, would have preserved dignity. By receiving Alice Roosevelt with an appropriate ceremony, the Sultan asserted continuity with his diplomatic past. He engaged the Americans on the terrain of ritual rather than force, using hospitality and protocol to maintain a semblance of sovereignty. Yet these gestures could not halt the structural transformation underway. American colonial administrators were already planning to dissolve treaty arrangements and extend direct rule. The meeting with Alice Roosevelt did nothing to alter this trajectory. Instead, it marked a moment when the old order was publicly displayed even as it was being dismantled behind the scenes.

The encounter also illuminates the broader American strategy in the Philippines during this period. After the formal end of the Philippine-American War in 1902, the United States sought to reframe its presence as benevolent and developmental. Educational initiatives, infrastructure projects, and public health campaigns were emphasized in official narratives. Visits by prominent Americans, including Alice Roosevelt, were part of this effort. They provided visual and textual material for audiences back home, reassuring them that the empire was compatible with American values. The meeting with the Sultan of Sulu fit neatly into this narrative. It suggested that even the most culturally distinct and potentially resistant populations were being peacefully incorporated into the American system.

This narrative obscured the reality of coercion. Within a year of Alice Roosevelt’s visit, the U.S. military launched a devastating assault on Bud Dajo in March 1906, where hundreds of Moro men, women, and children were killed. The massacre exposed the limits of accommodation and the willingness of American authorities to use overwhelming force to impose order. The Sultan of Sulu, though not directly responsible for the resistance at Bud Dajo, was powerless to intervene. His authority had become ceremonial, and his role had been reduced to that of a symbolic intermediary. The courtesy extended to him in 1905 stood in stark contrast to the violence inflicted on his people soon thereafter.

The dismantling of the Sultanate accelerated in the years that followed. American administrators redefined land tenure, imposed new legal systems, and integrated the region into the colonial state. By the 1910s, the Sultan’s political authority was effectively extinguished. What remained was a title without power, a relic of a pre-colonial order preserved for historical interest rather than governance. In this sense, the meeting between Alice Roosevelt and the Sultan of Sulu can be seen as a farewell performance—a final public acknowledgment of a sovereignty that was already fading.

For historians, the episode offers a lens through which to examine the mechanics of empire. It demonstrates how colonial power operates not only through armies and laws, but also through symbols, rituals, and personalities. Alice Roosevelt’s celebrity was not incidental; it was instrumental. Her presence transformed a political transition into a social event, softening its appearance while leaving its substance unchanged. The Sultan’s participation likewise reveals the constrained choices available to indigenous elites under colonial rule. Ceremony became a way to negotiate loss, to assert dignity in the face of inevitable subordination.

When Secretary of War William Howard Taft organized his inspection tour of American possessions and allied states in Asia, Alice Roosevelt’s inclusion was deliberate.

The encounter also complicates simplistic narratives of American exceptionalism. The United States often portrayed its imperial project as fundamentally different from European colonialism—more humane, more democratic, more respectful of local traditions. The meeting with the Sultan of Sulu was presented as evidence of this difference. Yet the outcome was indistinguishable from that of other empires: the erosion of indigenous sovereignty, the imposition of foreign rule, and the marginalization of local authority. The language and imagery may have differed, but the structure of domination remained.

In the longer view, the legacy of this period continues to shape politics and identity in the southern Philippines. Contemporary claims by descendants of the Sultanate, ongoing conflicts over autonomy, and debates about historical injustice all trace their roots to the American colonial reconfiguration of the region. The symbolic encounters of the early twentieth century, including that between Alice Roosevelt and the Sultan of Sulu, helped legitimize this reconfiguration. They provided a veneer of continuity and consent that masked deeper ruptures.

Alice Roosevelt herself would later reflect on her travels with a mixture of pride and irony. Known for her wit and irreverence, she was keenly aware of the performative aspects of her role. Yet even her self-awareness did not diminish the impact of her presence. For the Sultan of Sulu, there was no comparable platform from which to reinterpret the encounter. His voice survives only in fragments, filtered through colonial records and journalistic accounts. This asymmetry of representation is itself a product of empire.

In sum, the meeting between Alice Roosevelt and the Sultan of Sulu was a minor event with major implications. It encapsulated a moment when the American empire sought to present itself as modern, inclusive, and benevolent, even as it consolidated control through coercion and administrative absorption. It revealed how gender and celebrity could be mobilized to perform power, how ceremony could substitute for negotiation, and how sovereignty could be transformed into spectacle. As such, it deserves attention not as an anecdote but as a case study in the cultural politics of empire—one that illuminates the contradictions at the heart of America’s colonial experience in the Philippines.

For the author’s notes and sources, please email him at fabros1@ymail.com.

Photos provided by the author.

Alex S. Fabros, Jr. is a retired Philippine American Military History professor.

More articles from Alex Fabros, Jr.