A Guerrilla Ambassador Emerges from the Shadows

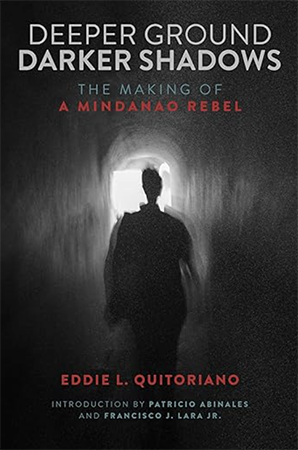

/Book Review: Deeper Ground, Darker Shadows: The Making of a Mindanao Rebel by Eddie L. Quitoriano (The University of Wisconsin Press, 2025)

The book documents events during one of the most turbulent periods in contemporary Philippine history—an era marked by martial law, state repression, dictatorship, and widespread human rights abuses. Its title evokes the many twists, turns, and complications that characterized Quitoriano’s life, much of it spent in secrecy in the rebel underground in both urban and rural areas, as well as in the international arena.

Activist Years

Quitoriano begins with his early years in Misamis Oriental in northeastern Mindanao. He entered a seminary for college, but his life changed dramatically after the First Quarter Storm of 1970, a period of militant—sometimes violent—protest actions by youth and students against the Marcos government. Demonstrators demanded an end to “American imperialism, domestic feudalism, and fascism,” identified in Philippine Society and Revolution (PSR) as the three basic problems that only armed struggle could resolve.

He initially joined Khi Rho, a group aligned with social democratic ideas. But after the declaration of martial law in September 1972, he and several Khi Rho recruits gravitated toward the legal national democratic movement, dominated by Kabataang Makabayan (KM) and Samahang Demokratiko ng Kabataan (SDK). These organizations led the protest rallies at Plaza Miranda, where fiery speeches were followed by marches to the US Embassy, often ending with confrontations with riot police.

Martial Law and Armed Struggle

With martial law driving the KM and SDK underground, Quitoriano—like many young radicals of the time—was drawn deeper into the clandestine movement, particularly to the Armed City Partisans (ACP). Their tasks included “agaw-baril” operations to seize firearms from police and military forces for guerrilla units in the countryside, as well as covert fund-raising missions for the underground.

Life in the underground meant constant danger—arrest, torture, and prolonged detention. Quitoriano recounts multiple arrests and periods of incarceration, as well as years on the run as an NPA cadre assigned to various rural guerrilla zones.

International Solidarity Work

Having proven himself within the organization, Quitoriano eventually rose to the top echelon of the NPA. He was appointed International Representative of the NPA General Command, tasked by the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) with securing political, material, and financial support from sympathetic countries—Yugoslavia, Libya, Cuba, and North Korea, among others—as well as liberation movements like the Sandinistas of Nicaragua.

These chapters are among the most riveting. Quitoriano traveled on fake passports, met clandestinely with underground networks—including the Japanese Red Army—and even underwent two plastic surgeries in Cuba to alter his appearance and avoid apprehension.

The Growth of the NPA

Other authors have written about the NPA’s birth in 1969, but Quitoriano revisits this history to contextualize its expansion. The early rebel force consisted of remnants of wartime guerrillas from the Hukbong Bayan Laban sa Hapon, later reorganized as the Hukbong Mapagpalaya ng Bayan (HMB), joined by younger fighters led by Bernabe “Ka Dante” Buscayno. Initially small and poorly armed, the NPA grew steadily and spread from Central Luzon to Northern Luzon, Southern Tagalog, the Bicol Region, the Visayas, and parts of Mindanao.

By the mid-1980s, the NPA reached its peak strength, estimated at 25,000 fighters. The CPP broadened its influence through united front work among workers, peasants, intellectuals, and even segments of the “national bourgeoisie,” who were persuaded to support the revolutionary cause.

Expanding the International Network

What distinguishes Quitoriano’s book from prior works is its detailed narrative of international efforts to support the revolution at its height. By the 1980s, the CPP-NPA believed it had reached the “advanced substage” of the strategic defensive and needed more sophisticated weaponry to move toward strategic stalemate—where the NPA could match the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) in combat capability.

But geopolitical realities intervened. China had supplied arms in the early 1970s, but after establishing diplomatic relations with Manila, Beijing retreated from exporting revolution. Other sympathetic states, like Libya and North Korea, offered assurances but faced immense logistical challenges in arms delivery.

The result: the strategic stalemate envisioned by the CPP-NPA never materialized.

Quitoriano argues implicitly that while protracted people’s war succeeded in China and Vietnam, it may no longer be viable in the Philippines. Advances in surveillance technology, drones, and long-range weaponry have transformed warfare, necessitating a reassessment of strategy by those who still believe in armed struggle.

Internal Purge of the CPP-NPA

In the epilogue, Quitoriano examines one of the movement’s greatest self-inflicted wounds: the anti–deep penetration agent (anti-DPA) purge of the late 1980s. Beginning in Mindanao with “Kampanyang Ahos” and spreading to Southern Tagalog’s “Operation Missing Link,” widespread accusations of infiltration led to torture, executions, and an estimated 2,000–3,000 casualties nationwide. The CPP Central Committee later condemned the purge as “sheer madness” and ordered it stopped.

Eddie Quitoriano (Source: Visus Consulting)

The damage, however, was immense. The killings created disillusionment, demoralization, and mass desertions, contributing to the CPP split into “reaffirmist” and “rejectionist” factions. The former upheld the strategy of protracted people’s war; the latter turned to alternative approaches, including electoral participation and “popular democracy.”

The Revolution in Decline

Beyond internal crisis, the revolutionary movement’s decline stemmed from battlefield losses, the arrest of numerous leaders over decades, and the hardships endured by underground operatives—family separation, insecurity, and the constant threat of death or capture.

Strategic Defeat?

The AFP now claims “strategic victory” over the NPA, noting that nearly all guerrilla fronts have been dismantled except for one. Although the military previously projected total defeat of the NPA by December last year, sporadic clashes still occur, mostly at the squad level—far from the NPA’s heyday when it could field companies of regular guerrillas.

Quitoriano argues implicitly that while protracted people’s war succeeded in China and Vietnam, it may no longer be viable in the Philippines.

What Happens Now?

After nearly six decades of armed struggle, prospects for radical transformation in Philippine society appear bleak. Political dynasties continue to dominate the political system, as illustrated by the trillion-peso flood control scandal.

Can change come through elections or through armed revolution? With the perceived decline of the CPP-NPA-NDF, neither the ballot nor the bullet presently seems capable of delivering swift or radical change. Yet so long as poverty and inequality persist, unrest and calls for transformation will remain—and future generations may again take up the challenge.

I recall a statement in a history book attributed to Salud Algabre, a prominent figure in earlier guerrilla movements. Asked whether their struggles were worth it, she replied: “No uprising ever fails; each one is a step in the right direction.”

To buy the book:

2) https://uwpress.wisc.edu/Books/D/Deeper-Ground-Darker-Shadows

Ernesto M. Hilario studied Political Science at the University of the Philippines and has worked for various government agencies, NGOs and mainstream media since 1978. He writes a regular column for the Manila Standard broadsheet and also works as a freelance writer-editor.

More articles from Ernesto M. Hilario