A Memoir of Courage and Hope

/Book Review: The Body Papers by Grace Talusan

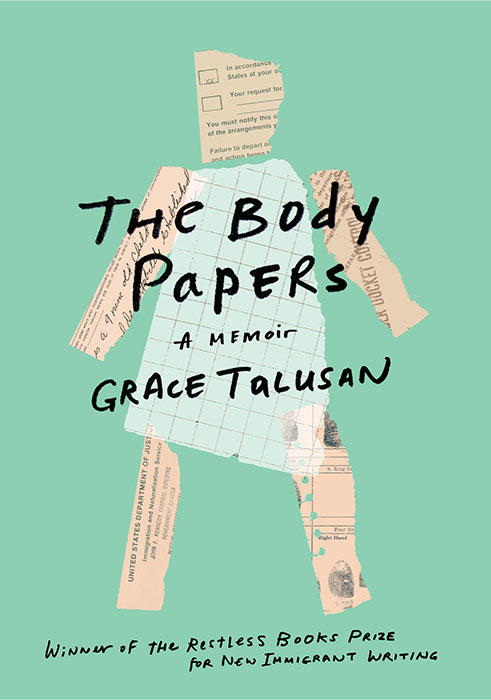

Restless Books, 2019

In awarding The Body Papers the 2017 Restless Books Prize for New Immigrant Writing, judges Anjali Singh and Ilan Stavans cited Talusan’s skill in “training an unflinching eye on the most delicate and fraught contours of her own life as an immigrant and survivor of trauma and illness.” In eloquent and oftentimes profound prose, Talusan examines her actions and the actions of others around her without self-pity, without assigning blame, and ultimately embraces big-hearted gratitude. And we, the readers, especially Filipino and Filipino-American readers, are equally grateful for Talusan’s gift of prose, of self-examination, of sharing her journey. Most importantly, we are grateful that she has paved the way for others to break the silence and become empowered through the written word.

There are multiple narratives that run through The Body Papers—sexual abuse and its aftershocks in the form of severe bouts of depression and anxiety, discovery of Talusan’s undocumented status, the racism and alienation she endured growing up in America, her family’s devastating history of breast and ovarian cancer and the menace and burden of being a BRCA1 gene carrier, and the heartbreaking decision made with her husband, Alonso Nichols, to not bring children into the world. What connects these narratives is Talusan’s desire for truth and understanding. It is through books that Talusan is able to survive (“My library card was a house key to my true home,” she writes) and through telling stories that Talusan finds her voice.

Throughout the book, photographs and documents, such as her passport, letter, handmade birthday card, medical test results, create a visual journey—a companion to her prose—through Talusan’s life, from the Philippines to America and back to the Philippines, from childhood to adulthood, from her primary and extended family to her own family of two. As a journey, these photographs and documents connect all the narratives.

The Body Papers opens with Talusan returning to her homeland on a Fulbright scholarship forty years after she left the Philippines at the age of two. The homecoming brings mixed emotions: She feels the pull of history and home, and yet, she has been gone long enough to feel like a stranger here. The moment she speaks with her American accent, she is no longer a native. She understandably identifies more with the Americans abroad, even though she has experienced racism—both unintentional and deliberate, and individual and institutional—throughout her life in America. Later in the book, she writes, “In the Philippines, I am an Amerikano, a returner, a balikbayan. I’m here to learn what it means to be Filipino, but somehow I’ve only become more American.” This is a phenomenon that many Filipino-Americans have come to experience upon returning home. The opening essays serve as an entry to the many narratives of Talusan’s life.

Grace Talusan (Photo by Alonso Nichols)

Talusan’s father, Totoy, came to America in 1974, two years after President Marcos declared martial law in the Philippines. He had hopes of returning home as an American-trained eye surgeon. Soon after his arrival, Talusan, her mother, and her older sister joined him in Boston. They settled into their lives and the family added three more—all natural-born U.S. citizens. “And before we knew it,” Talusan writes, “one year had turned into five, and, in a blink, 17 years passed without us ever returning home.” What she didn’t realize—until a trip to visit relatives in Canada provoked anxiety in her father—was that her father never filed any paperwork or pursued his employer’s promise of visa sponsorship, and as a result, her parents, her older sister, and she were classified as undocumented immigrants. While Talusan eventually became a naturalized citizen, those years were filled with fear over being discovered and deported, which added to her alienation.

Talusan grew up in the Boston suburbs with few Asian Americans around. She sought what many Filipino immigrants desired: a rejection of one’s culture, from food to language, in order to completely assimilate, which, of course, is never allowed. Talusan battled the stereotypes of Filipinos that made their way into America and the ignorance of her classmates and even, though not surprising for the time, her teachers.

The onslaught of bigotry outside the home already made her vulnerable and fragile, but nothing was more devastating than the sexual abuse by her paternal grandfather from the age of seven until the age of thirteen in her basement bedroom. Talusan kept quiet for many years, unable to process what was happening to her, assigning self-guilt that she had somehow brought this upon herself. But she also acknowledged that to remain mute was keeping in line with her family’s modus operandi: “This is part of our family’s genetic code: to deny and dismiss.” Talusan writes of her fear: “I’m not afraid of falling apart by remembering, but I am scared of how this information can be used against me.”

The aftershocks of this trauma followed her for years. In college, she fell into a deep depression and suffered severe bouts of anxiety that paralyzed her. She writes: “I was to believe that I was invisible,” and “I just wanted to be asleep, to experience oblivion.” It took several years of therapy and the love of her family and her husband, Alonso, for Talusan to make it to the other side. “Reaching out to other people and connecting, which is the exact opposite of how I felt when I was being abused, is why and how I am alive,” she shares. “All this work in healing has made it possible for me to have a life.”

Perhaps overcoming this trauma prepared her to deal with the family cancer that ravaged her father’s side of the family, including Tessie, her elder sister, and her niece, Naomi. The clarity of Talusan’s prose is heartbreaking and startling: “After months of research, surveillance tests, and conversations, I agreed to a preventive mastectomy scheduled for the day after my fall classes ended. In the days before the surgery, I stopped in front of the bathroom mirror after showering to memorize my breasts. In the sleepless nights before the surgery, I held my breasts in my hands. I thought of how the first buds appeared through my electric-blue dance costume at age eleven; how water felt like velvet when I swam topless with my girlfriends in the summer.”

Talusan writes poignantly of her desire to have children, which was compromised by her biological clock running out, being a BRCA1 gene carrier, and Alonso’s uncertainty over becoming a parent as a result of a childhood that was betrayed by the presence and then absence of a verbally abusive, neglectful, and alcoholic father. When Alonso tells Talusan he does not want to have children, she writes, “I’d wonder if I’d married the wrong person.” Not only is Talusan devastated by the reality, but we readers are too, and that sorrow is heightened by her straightforward accounting. Marriages end with such proclamations, when there can be no compromise. Yet, Talusan, realizing that their love is bigger and stronger than these life-changing decisions, writes, “But every time my husband burst through our front door after a run, exuberant and sweaty, I would feel overjoyed that he had returned to me. We shared responsibility. Faced with impossible decisions in which only one of us could win, we let it go and go, until now we were here, cooking for two.”

That sense of big-heartedness permeates The Body Papers. And it is through the gift of prose that Talusan embraces such generosity. When she was a child, her grandmother, Mama Lola, told her that she was becoming just like her nephew, Alfrredo Navarro Salanga, a journalist, poet, fiction writer, playwright, and critic. Talusan took this as a compliment of the highest order. Mama Lola gave her Tito Freddie’s book, which was the first she had ever read by a Filipino writer. Talusan looked up to her Tito Freddie, and indeed, followed his footsteps. Talusan writes, “Tito Freddie died before we could meet in person, but his conviction taught me that a writer sets words down, one after the other, which offer new, expansive possibilities.” Like the baby steps she had initially taken to free herself from the years of trauma, Talusan began to write, one word after the other. While she has given herself a life of new expansive possibilities, so, too, has she given us a book of hope.

Patty Enrado's debut historical novel, A Village in the Fields, was shortlisted for the Seventh William Saroyan International Prize for Writing, Fiction, 2016. She lives in the San Francisco Bay Area.