Violinist Gilopez Kabayao and Pianist Corazon Pineda’s Love Story

/Gilopez Kabayao and Corazon Pineda in 2023

Music was in the blood of Gilopez Kabayao. His father Doroteo Kabayao of Bugasong, Antique, had studied medicine at the Rush University Medical College of Chicago, as well as the violin in Berlin. Dr. Kabayao also composed songs. Gilopez’s mother Marcela Hofileña Lopez of the illustrious Lopez clan of politics, media and industry, sang and played the piano. Although Dr. Kabayao was mainly involved with running their family’s vast hacienda in Negros Occidental, and in Iloilo, he also set up a medical clinic and a little music school in Hacienda Faraon, Cadiz City, where he raised his family. The Kabayaos were Aglipayan, but the American Baptists in the lumber mill at nearby Fabrika convinced Gilopez to convert. He took his faith so seriously that later, a spiritual hymn or praise song was part of all his Philippine outreach lecture concerts.

Calbayog, Samar Lecture Concert for 8000 people

Gilopez and his younger sister, Marcelita, showed signs of being musical prodigies in their teens. After WWII, they continued their music lessons in New York City, with Gilopez under the tutelage of the Viennese husband-and-wife teachers Theodore and Alice Pashkus who had also mentored Yehudi Menuhin.

Corazon Pineda’s father Francisco Pineda also instilled in his children an appreciation for life’s finer things, like classical music. Mr. Pineda played the violin for pleasure. He had his two daughters take piano lessons at the Lukban Academy, where he was the principal. Their music teachers had trained at the UP College of Music and the UST Conservatory. Soon, the younger Corazon overtook her older sister, Milena, and was mastering lessons far in advance of what her teacher Mrs. Villaseñor had assigned. Nurturing her potential, Mr. Pineda made sure his ten-year-old daughter attended the single show at the Sacred Heart Academy of Lucena by the Austrian pianist Rudolf Serkin, considered one of the world’s foremost interpreters of Beethoven. Live performances by foreign artists were a rarity. Tickets were pricey, so this was a precious father-daughter date that left a lifelong impression.

Young Corazon first learned of Gilopez Kabayao’s international concert career on the pages of Kislap Graphic. Handsome, and impeccably groomed in his bespoke tuxedo, he was quite the heartthrob with his 250-year-old Stradivarius but seemed a world apart. Nonetheless, when Corazon and her high school classmates at Lukban Academy, went on a field trip to the Philamlife Auditorium which had the best acoustics then, the unbidden thought came to her that someday, she would be up on that very stage, playing with an orchestra.

Playful Role Reversal

Back in the 1960s, there was the Manila Symphony Orchestra (MSO) Youth Concert Soloist audition, a precursor of today’s NAMCYA (National Music Competition for Young Artists). Accompanied by her mother, 15-year-old Corazon entered the junior category, for young soloists up to age 18. She was the only provinciana to qualify. Thus, that April 1965, she got to play a Mendelssohn movement on the stage of the Philamlife Auditorium, accompanied by the Manila Symphony Orchestra. Her piece was quite a contrast to the more dramatic Prokofiev, Katchatourian, and such, which the nine other young concert soloists chose, but it was the fulfillment of her earlier vision.

Still at the tender age of 15, she enrolled in music at the UST Conservatory. Her older sister, Milena, was already at the College of Education. Mindful of the financial strain educating several children in Manila placed upon their parents back in Lukban, Corazon took the bold step of approaching the UST Rector for a scholarship. The rector asked why he should consider an unproven freshman. Corazon pointed out she had qualified in the junior category of the MSO Youth Concert Soloist audition and played for him. The rector was persuaded to grant her the scholarship, which she maintained until she graduated five years later. She credits the UST Conservatory janitor with urging her to make this unprecedented move of applying while just in her first year. Perhaps even he had realized how advanced she was from listening to her play.

In 1968, in her 4th year as a piano major, Corazon qualified for the senior category of the MSO Youth Concert Soloist audition. Then came the Feast of St. Cecilia, patroness of music, which the UST Conservatory customarily celebrated with recitals and a convocation. Gilopez Kabayao was among the invited speakers that year. Afterwards, the violinist Prof. Sergio Esmilla Jr., who was teaching at the Conservatory, introduced Corazon and three other piano majors to Kabayao, who was looking for an accompanist for his upcoming provincial tour. The young pianists thought it was unusual that Kabayao would consider a student, as he usually had such established pianists as Regalado Jose, Reynaldo Reyes or Stella Goldenberg Brimo to accompany him.

Corazon played her MSO Youth Concert piece: two movements from the Chopin F Minor Concerto. Kabayao turned to Prof. Esmilla and declared, “What a revelation!” He opted not to listen to the two remaining pianists and forthwith asked Corazon if she would be his accompanist on his upcoming provincial tours that December. When she agreed, he gave her an inch thick sheaf of sheet music. She asked him if she would have to play them all, and the reply was a pleasant though cryptic, “Perhaps.” Fortunately, she was an exceptionally adept sight reader, which not all musicians are, but is especially useful for an accompanist. Ideally, to prepare for a concert sonata, one would need several days just to study the notes, then more days of playing together to perfect this.

And so, two weeks later, Corazon took her first plane ride, and performed with Gilopez Kabayao on an open-air stage, for sugar planters of Sagay, Negros Occ. The acoustics as well as the condition of the piano provided were challenging, to put it mildly, but this was not unusual for Kabayao who had been known to perform in cockpits, a boxing ring in Cebu and even in prison yards. Sometimes they gave nine concerts in four days, at least ten numbers per concert. Nothing compares to a live performance where the artist immediately enjoys the deserved appreciation.

Despite his stature as an artist, Kabayao was singularly even-tempered, or of a non-artistic temperament, if one goes by the volatile diva or Primadonna stereotypes. He laughed easily and was quite sociable and genuinely interested in other people. He did insist on arriving at the venue early so they could check the conditions of the stage, and for Corazon, of the piano provided.

Corazon played her MSO Youth Concert piece: two movements from the Chopin F Minor Concerto. Kabayao turned to Prof. Esmilla and declared, “What a revelation!”

“I want you to play with me,” he would tell his young accompanist. “Not to merely follow me.”

Corazon noted the concentration they both required during each performance: moving, playing, thinking, breathing as one, in sync and in full commitment to the teamwork expected of them. The accompanist was a collaborative artist in concert.

Thus, the musical partnership between Gilopez Kabayao and Corazon Pineda grew and flourished. They were together in the United States when Marcos declared martial law and when Gilopez was given the Ramon Magsaysay Award for Public Service for “his leadership on the renaissance of the performing arts, giving a new cultural content to popular life.” Due to the uncertainties of the newly imposed Marcos martial law dictatorship, which had immediately targeted his Lopez uncles’ corporations and imprisoned his cousin Eugenio “Geny” Lopez Jr., Kabayao did not yet return to Manila, and had his mother accept the award for him.

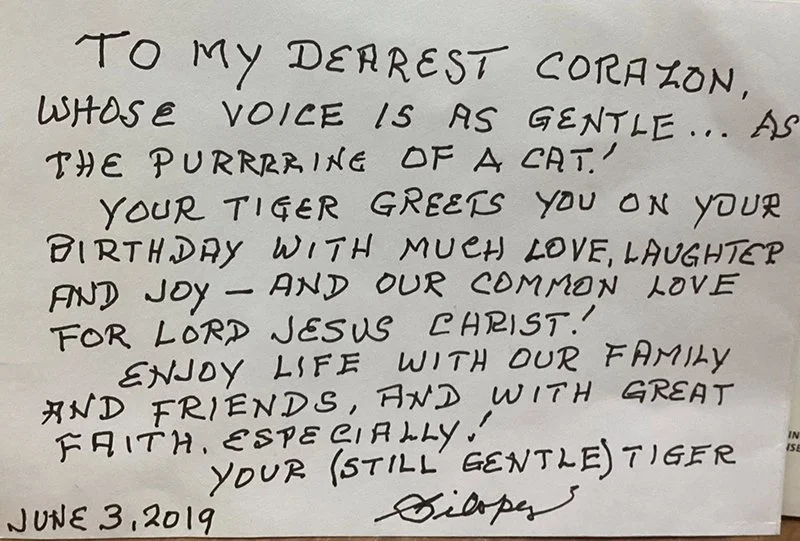

On Feb. 16, 1974, Corazon and Gilopez Kabayao were married in Los Angeles, CA. The wedding date was the closest they could get to Valentine’s Day which fell on a Thursday that year. Corazon liked to tease him about how lucky he was to have a much younger wife to take care of him. In loving notes and cards to her, he signed himself as “The Tiger.” He described her as his always gentle purring pussycat. Along with his buddies, Doctors Gil Villanueva and Emil Salcedo, he proudly proclaimed himself a founding member of UHAW (Union of Husbands Adored by their Wives).

With Love from “The Tiger”

Married in L.A. on Feb. 16, 1974

With marriage, Corazon played a greater role in organizing their lecture concerts and performances. They returned to Manila in the late- ‘70s as they had always wanted to raise their children as Filipinos in the Philippines. Sicilienne, Farida, and Gilberto all played the violin and would later perform with their parents as the Kabayao Family Quintet. With the advent of the Art Councils in the 1980s, Gilopez and Corazon got a grant to make a Listening Program for Filipino Youth: educational cassettes of classical and Filipino music intended from grade school to college students which were distributed throughout the 13 Regions.

The Kabayao Family Quintet in 2024: From left to right: Farida, Gilopez, Corazon, Sicilienne and Gilberto

Music should be experiential, not the meaningless memorization of notes and symbols which it often is under the DepEd’s MAPE curriculum. The Kabayaos engaged joyfully with students and common folk, adroitly guiding them through classics and Filipino folk songs. Audiences were urged to tap and sway to the rhythm. They were made aware of how the melody stirred up their emotions or touched their hearts. Then came the intellectual and creative stages as their minds were stimulated and their imaginations took flight. A recent session with several thousand Central Philippine University high school students proved such active listening could prevail over cellphone screens.

Although Gilopez is known as the Father of Filipino Outreach for his ground-breaking efforts to bring classical and Filipino traditional music to wider audiences, the Kabayaos, whether as a husband-and-wife duo, or later as a family quintet did not play for free, or out of charity. They believed that artists should be treated as respected professionals, hence they should be paid commensurately. Tickets for their many lecture concerts in schools and rural communities were sold at very reasonable prices though, never higher than what one would pay for popular entertainment, like a movie.

Kabayao had the profound satisfaction of knowing his name would live on when his only son, Gilberto, became the father of little Girard in mid-2024. He was unable to travel to the States to personally meet his grandchild, but enjoyed face time with the baby before he passed away in Iloilo City at age 94 last October 2024. The loss of her spouse and fellow performing artist has been especially difficult for Corazon.

Teaching only son Gilberto to play the violin

For months, her deepest mourning was expressed in silence. Six months after his passing, she was unable to play the piano. Worst of all, she had even stopped listening to music or watching any concert performances on YouTube as she and Gilopez used to every night. Then one day, she found herself playing a couple of Chopin Etudes. Her healing had begun. Now, she can listen again to the music they used to enjoy together, and “accept the beautiful gift of music as a healing balm, akin to a sweet word of comfort from God, a whispered promise for less painful days.”

This Thanksgiving and all the way till after the Christmas holidays, the Kabayao family will all be together in California. Little Girard will finally meet his lola and aunts face to face. And so, life’s cycles continue and the music plays on.

Maria Carmen Sarmiento is an award winning writer and the former Executive Director of the PAL Foundation. She can be reached at menchusarmiento@gmail.com; menchusarmiento@ymail.com.

More articles from Maria Carmen Sarmiento