The Unforgettable Macli-ing Dulag

/[Excerpts from “MACLI-ING DULAG: Kalinga Chief, Defender of the Cordillera” (University of the Philippines Press, 2015)]

April 24, the date of Macli-ing’s death has, for many years, been celebrated as Cordillera People’s Day. Wrote sociology professor Randy David: “People who had done solidarity work in the struggle against the Chico Dam project usually congregate on this day in Bugnay, not only to honor the memory of a dead man but to keep alive the dream of a united Cordillera.”

David remembers Macli-ing and Bugnay: “I first visited this place (in 1978) as part of a contingent of journalists and activists from Baguio and Manila who had been invited to witness a bodong of various Cordillera tribes and villages."

“Macli-ing presided over a novel application of this traditional concept in order to unify the villages that were to be affected by the government plan to put up four dams along the Chico River. He brought together villages that had been enemies in the past, or mutually isolated from one another. For the first time, village elders from different tribes found themselves in one another’s presence, talking about a common threat.”

The Chico River (Source: Baguio Hearld Express)

Lawyer William “Billy” Claver said that tribal conflicts were set aside when the dam threat loomed and Macli-ing rallied the tribes to stand together. “We were able to forge a modus vivendi among the warring tribes when it came to the dam issue,” said Claver. Macli-ing explained the issues well, he had a gift of tongue, so to speak. “Among the tribes there was not one dialect,’’ Claver said, “but when Macli-ing spoke, everybody understood. Even the soldiers.” Standing about five feet and six inches tall, the barefoot Macli-ing, sometimes wearing only a G-string, cut a powerful figure.

Claver has fond memories of the pangat (tribal chief) although the two did not start out as friends. “In the late 1960s Macli-ing was after my neck because I was lawyering for Lepanto Consolidated Mines. Macli-ing did not like the intrusions into ancestral lands. But around 1976, freshly out of the Constitutional Convention, I made a turnaround.”

That was when opposition to the Chico River Project was peaking. Claver, an Igorot, sympathized with the Kalinga cause. “Macli-ing and I became friends. Whenever he came to Tabuk he would visit me. He even saved my life.”

A tribal war between the Butbuts to which Macli-ing belonged and the people of Sandanga was raging then. A group of Butbuts was about to attack a jeep where four Sandanga tribesmen were riding and Claver happened to be in the same vehicle. Macli-ing who was then a road worker saw Claver and stopped the ambush.

“Macli-ing taught me about a Philippines I had never known—and have only really seen in those mountain barrios. Macli-ing’s home was the land and his honor came in preserving that land for his people.”

After Macli-ing’s death, Claver was among those who called for the celebration of Cordillera Day on April 24 in honor of the martyred pangat. Claver disputed any other reason—political or ideological—for the celebration date, which was being spread around by individuals who wished to smear the memory of Macli-ing and belittle his sacrifice for their own aggrandizement. Claver was prosecuting lawyer at the court martial that tried Macli-ing’s killers.

Lin Neumann, a former human rights volunteer from the U.S. of the United Methodist Church in the 1970s (and later consultant to the Southeast Asian Press Alliance in the 1990s) had met Macli-ing and written about him when the pangat was still alive. His recollections in 1999: “I was fortunate enough to meet Macli-ing Dulag during the days when everything in the Philippines was new to me. As a volunteer intern on human rights in 1978, I was traveling for several weeks in the Cordillera, which was experiencing a great deal of tension due to the plans by the Marcos regime to build a hydroelectric dam in the Chico River basin.

“The threat of the Chico River dam had given the (communist-led) New People’s Army (NPA) an opening to begin organizing among villagers in the region and as a result, there was a large military presence in the area."

“The center of much of the resistance to the dam was in the village of Bugnay, which would have been submerged by the dam and whose leader was Macli-ing Dulag. During my travels I was invited to attend a bodong (tribal gathering) presided by Macli-ing and attended by representatives of several villages. The intention of the meeting was to solidify local opposition to the dam using traditional forms and rituals."

“Whatever the influence of the Left in the area, it was clear that Bugnay was Macli-ing territory. The local cadre of the NPA knew that they should defer to him and that it was Macli-ing whose voice counted in Bugnay. His presence was both a warning and a comfort to an outsider. The warning came in knowing that this well-muscled man, with his fierce hawk-like eyes, held sway in this village and that one was well advised to behave honorably toward him and his people. The comfort came in learning to see the Cordillera through his vision and the tales of his people."

“He invited me to stay in his home during the bodong, and I was honored to do so. I sat by the fire for hours into the evening as he and the other elders recited long tales of their proud struggle against the Chico Dam project. There, in the clean fresh air of the far north, Macli-ing taught me about a Philippines I had never known—and have only really seen in those mountain barrios. Macli-ing’s home was the land and his honor came in preserving that land for his people."

“While I can no longer recall the exact words he spoke—always through a translator—the impact of his considerable presence has stayed with me ever since. There are people on this earth who radiate power and honor by their very being. I felt that way about Macli-ing during the times that I met him before he was assassinated by soldiers too cowardly to allow him to live."

“I remember that when he spoke at the bodong ceremony, all eyes turned toward him and all conversations ceased. It was as if the people in these villages were drawing their strength to resist the dam directly from the spirit of Macli-ing. I had the feeling that the modern world, with hydroelectric plans and development projects, would have to run directly through Macli-ing, if it was ever to penetrate his village."

“I had been told, before entering the village, that the Left was a great influence in Bugnay but I never found that these people of the Cordillera took any real interest in ideology. They were people of the land and their land was threatened. Macli-ing was their guardian and emissary."

“For me, he was a teacher. His words, his stance, his charisma and stubborn insistence on the sanctity of his people’s land, taught me that there were places in the Philippines where money did not speak and where power resided in something other than armed strength. I will never forget him.”

Author’s Note

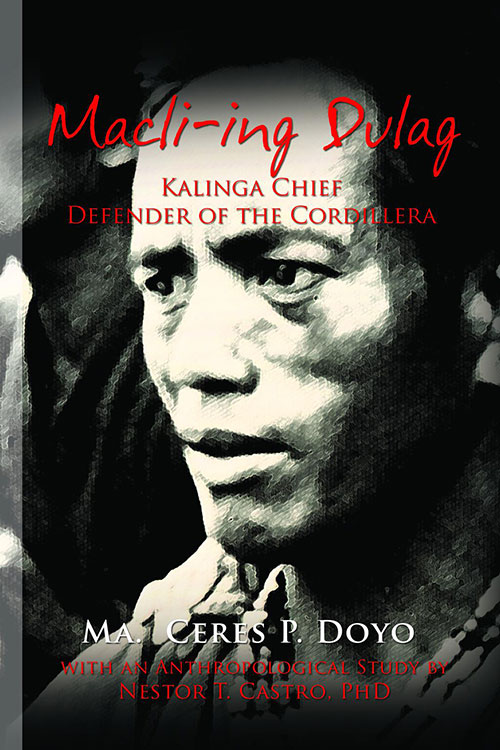

The name of Kalinga chief Macli-ing Dulag is etched on the black granite Wall of Remembrance of the Bantayog ng mga Bayani in Quezon City, one of the hundreds of names of honored martyrs and heroes who fought, suffered and offered their lives for freedom, justice and truth during the dark years of the Marcos dictatorship’s martial rule.

Macli-ing led the fight against the construction of dams on the Chico River, dams that threatened to wipe out ancient Kalinga way of life. If not for the Kalinga chief’s leadership and bold utterances of truth to power, whole communities would have been uprooted and scattered.

This book is yet another way of honoring and keeping alive the memory of the man who fought for his people, the Kalinga people, whose mountain homes were marked to give way to so-called development.

Macli-ing’s struggle that led to his death on April 24, 1980 served as a watershed moment.

My story on Macli-ing (he is more known by his first name) in this book is an expanded version of my award-winning 1980 magazine article that led to my first interrogation and chastisement by military authorities. The article also put my editor in trouble with her publisher and the powers-that-be at that time. But the piece earned a journalism award handed to me by no less than Pope John Paul II (now a canonized saint) during his 1981 visit.

The recognition was a Magnificat moment for me. And in those dangerous times, it signaled the beginning of my writing career and affirmed my human rights advocacy through writing.

The story on Macli-ing’s life and death is best understood in the context of the history and culture of the Cordillera, the mountainous ancestral domain of several major indigenous communities. Dr. Nestor T. Castro, current head of the University of the Philippines’ Department of Anthropology, so willingly wrote an accompanying study on the Cordillera that complements the story on Macli-ing. Our two written works were first included in the book Seven in the Eye of History (Anvil, 2000) edited by Asuncion David Maramba.

Dr. Castro’s piece, which makes up the second part of this book, provides context, a looking glass, so to speak, through which the reader can view and better understand the Cordillera mountain society that Macli-ing so fiercely defended.

April 24, 2015 is Macli-ing’s 35th death anniversary. (April 24 is now celebrated as Cordillera Peoples Day.) This book is a way to remind Filipinos and those in foreign lands who supported his cause about the essence of his struggle and the price of triumph. The younger generation, particularly those in the Cordillera, needs models like Macli-ing.

I am honored to have, as publisher, the University of the Philippines Press, which made this book affordable and easily available to many.

While working on this book project, I also had in mind the newly formed Memorial Commission that is mandated, through Republic Act 10368, “to honor the memory of the victims of human rights violations….” This law, signed by Pres. Benigno Aquino III on February 25, 2013, stresses that “the lessons learned from Martial Law atrocities and the lives and sacrifices of HRVVs (human rights violations victims) shall be included in the basic and higher education curricula, as well as in continuing adult learning, prioritizing those most prone to commit human rights violations.”

Here’s to the Kalinga Brave. You will not be forgotten.

Ma. Ceres P. Doyo has been a journalist for more than 30 years, 25 years as a staff writer of the Philippine Daily Inquirer where she writes a weekly column "Human Face."

More from Ma. Ceres P. Doyo:

Mother Of All Devotions

May 22, 2013

The coffee table book Pueblo Amante de Maria is a guide to Marian shrines in the Philippines.