The Battle of Tamparan and the Forgotten Moro Heroes of World War II

/Map of Mindanao

In 1903, U.S. Captain John J. Pershing had launched a brutal campaign to “pacify” the Maranao communities around the lake through overwhelming force—one that resulted in at least 400 Maranao deaths by artillery fire.

In 1942, the Japanese army attempted their own pacification program. Initially, every household was required to turn in all firearms, while chopping tools were limited to one for every two households. The Maranaos surrendered a few defective rifles and some old rusty blades. The Japanese then threatened to shoot any Maranao they found with a gun and did so, executing each violator immediately in a public square. Those public executions provided the initial spark for an eventual wildfire of Maranao retaliation.

In June 1942, the Japanese commander of the Dansalan garrison sent a punitive expedition to Watu, a small village on the western shore of the lake, looking for Manalao Mindalano, the first Maranao leader to launch attacks against them. The surprised villagers of Watu, who had no connection to Mindalano, were trapped against the lakeshore as they tried to escape the soldiers, who methodically bayoneted men and women alike, killing 24 in all.

In reprisal, the Maranaos attacked a Japanese convoy, firing well-aimed volleys into the drivers and tires of speeding trucks and sending them careening off roads and tumbling from bridges. The Japanese responded by burning scores of houses along the road where the ambush was laid. The cycle of retaliation was underway.

The Battle of Tamparan

In September 1942, the Maranaos dealt the Japanese a stunning loss when, in a spontaneous attack, a collection of villagers armed primarily with blades nearly annihilated an entire company of Japanese infantry. The Battle of Tamparan was the gravest defeat inflicted on the Imperial Japanese Army by irregular forces in the Philippines and quite likely their greatest loss at the hands of civilians in the entire course of the Pacific War. For the Japanese infantry, it was a defeat as improbable, shameful, and symbolically charged as that suffered by the U.S. cavalry at the Battle of the Little Bighorn but, unlike that iconic defeat, it has been mostly lost from history.

Map of Tamparan

The patrol of 90 Japanese infantrymen arrived in the small lakeside town of Tamparan at dawn in three launches on the morning of September 12th, the first day of the Muslim holy month of Ramadan. They were looking for a Maranao resistance leader who was no longer in the village and, when challenged, opened fire with mortars and other weapons. Attacking a Maranao settlement on the first morning of the most sacred month of the Muslim calendar was a fatal mistake. The fasting month in Tamparan celebrated selflessness and mutual aid as the highest moral principles of the community, principles that birthed a terrible resolve for total resistance on that fateful morning.

The sound of the shelling brought Maranaos from Tamparan and its surrounding villages, weapons in hand, running to the scene. Those with rifles crawled through the marsh grass and fired on the Japanese ranks from the rear. Those armed only with blades, the large majority, rushed straight down the road at the invaders and into a cyclone of bullets and shrapnel.

Eventually surrounded on three sides and taking casualties from both bullets and blades, the Japanese soldiers, their ammunition exhausted, broke and ran for the pier and the launches but were soon mired in the marshlands that edged the lake. Now they fought without bullets, desperately using their bayonets to parry blades, their boots sucking them into the mud while the barefoot villagers rushed in from all sides.

Lakeside marsh at Tamparan (Source: Wikimedia.org)

Some soldiers attempted unsuccessfully to surrender. One of the company’s officers, First Lt. Atsuo Takeuchi, made it back to the pier with a few of his men, but the boat crews, who were forced laborers, had dived overboard when they saw how the battle was going. With no way to escape, he dropped his sword and raised his hands in submission. Takeuchi had been very active in propaganda efforts among the Maranaos and had often bragged that the Japanese, unlike the Americans and Filipinos, never surrendered. According to Edward Kuder, an American colonial official hiding with the Maranaos, and the only contemporary chronicler of the battle, one young Maranao remembered those boasts and yelled, “No surrender, Takeuchi!,” before cutting him down with his sword.

Of the 90 Japanese infantrymen who marched down the Tamparan pier that morning, 85 now lay dead on the muddy lakeshore; their lacerated bodies, sprawled individually or tangled together in clumps of blood-soaked khaki, dotted the trampled grey marshland. But Japanese rifles and mortars had also taken a heavy toll on the defenders of Tamparan. In death, as in life, the Japanese soldiers were surrounded by Maranaos. In every direction lay the shattered bodies of villagers, more than 200 in all, who had run to the aid of their neighbors on that sacred morning with blades drawn to meet the terrible firepower of the Empire of Japan. The sound of keening soon pierced the air and rose and flew from settlement to settlement along the lakeshore as families discovered the bodies of their loved ones on the field and carried them home to prepare them for burial.

The Japanese bodies lay where they had fallen. For two days afterward, the terrible reek of their corpses bloating in the heat kept villagers from the battlefield. The Japanese commander at Dansalan, Lt. Colonel Yoshinari Tanaka, offered rewards for the return of the bodies of his soldiers, and a few enterprising Maranaos stole bodies, despite the stench, and sold them to the Japanese.

The body of First Lt. Takeuchi had been mutilated beyond recognition, with scores of wounds from blades. In his account, Edward Kuder explained the mutilation by noting that the Maranaos were simply “blooding” their weapons because of their belief that “before a weapon can become fit to use, it must many times taste blood.”

A Maranao survivor of the battle, Abubakar, recalled differently 52 years later in an interview with historian Kawashima Midori. A farmer from Tamparan, Abubakar was at home that morning when he heard the firing. He grabbed his bolo and joined “a great crowd” that had gathered from surrounding villages. He then took part in the fighting, “narrowly escaping death.” He remembered that Takeuchi’s body was mutilated because “people felt angry seeing so many of their friends injured or dying.”

Tamparan today (Source: Mapio.net)

Tamparan buried its dead, but its suffering was not over. To punish the villagers, the Japanese attacked the town and its surrounding settlements for 25 days straight, but only from afar, using aerial and artillery bombardment. Edward Kuder reported that the bombardment was ineffective and killed no Maranao fighting men. But Mohammad Adil, a guerrilla officer, remembered hearing of one Japanese bomb that struck a mosque where villagers were seeking shelter, killing 80 men, women, and children.

The victory at Tamparan, costly as it was, inspired even more Maranao resistance. In response to the retaliatory bombings, the Maranaos destroyed the road leading to the lake, felling trees for miles and obstructing culverts so that rains would wash the roadbed away. They also laid siege to the Japanese garrison at Ganassi.

A Separate Victory

As the end of 1942 approached, the three Japanese garrisons around Lake Lanao were cut off from one another, with one of the three under active siege. New propaganda measures by the Japanese Mindanao Military Government signaled a sharp turn toward conciliation. The new measures focused on placating the Maranaos, abandoning the demand that they turn in firearms, and avoiding angering them in other ways. Just half a year after the Japanese occupiers of Lanao had set out to pacify the Maranaos, it was they themselves who had been tamed and surrounded. The Maranaos of the Lanao Plateau had effectively won their war of resistance against the Japanese before the American-led guerrillas recognized by Douglas MacArthur had fully begun theirs.

Edward Kuder, who had not made contact with American guerrillas until December 1942, wasted no time. Kuder had seen what the Maranaos could accomplish and he knew what the leader of the fledgling American guerrilla force in Mindanao, Wendell Fertig, needed. In January 1943, his last month on the Lanao Plateau, he contacted the Maranao resistance leaders of Lake Lanao, who had subdued their Japanese occupiers and secured their communities, and urged them to ally with the Americans.

By the end of the month, Kuder had convinced most of the active Maranao resistance leaders to join the American-led guerrilla force. Those Maranao leaders and their fighters formed the core of the Maranao Militia Force. They saved Wendell Fertig when he was cut off and surrounded by Japanese assault forces in June 1943, and sheltered him and his staff in their villages. And in April 1945, they captured the Japanese garrison at Malabang and occupied that strategic coastal town, allowing the invading Americans to shift more of their forces south to Cotabato and liberate Mindanao more quickly.

Members of the Maranao Militia Force, 1943 (Source: The MacArthur Memorial)

Guerrilla Chieftains in Cotabato and Bukidnon

In Cotabato and Bukidnon, other independent Moro resistance fighters also made remarkable gains against the Japanese occupiers before the American guerrilla movement had begun to operate. In the upper Cotabato Valley, Datu Udtug Matalam, the future governor of Cotabato Province, had a large community of Christian evacuees from Davao living happily under his protection in a town the Japanese had never visited—one with plentiful food, a library, an orchestra, and a clubhouse. Datu Udtug had so harassed the local Japanese garrisons in 1942 that they went to extraordinary lengths to avoid his ambushes, even sending medicine and cigarettes to his armed force.

In Bukidnon, 30-year-old Salipada Pendatun, brother-in-law of Udtug Matalam, foster son of Edward Kuder, and a man destined to become the most powerful and prominent Moro of his generation, led a highly-disciplined armed force that was larger than Fertig’s and included American officers. He was loved by his soldiers, who had elected him to the rank of Brigadier General, and admired by both Muslim and Christian civilians, for whom he provided government services.

In a six-month period in late 1942 and early 1943, Pendatun drove the Japanese from their Bukidnon garrisons, recaptured the Del Monte airfield and the provincial capital, Malaybalay, and for good measure, led the very first successful raid on a Japanese POW camp. When Wendell Fertig first contacted Pendatun by radio in January 1943, telling him of his organization, Pendatun offered Fertig a position on his staff.

Wendell Fertig, Douglas MacArthur’s choice for Guerrilla Chief of Mindanao, was not amused. He sent multiple emissaries to Pendatun in Bukidnon, seeking his “submission.” Pendatun resisted their entreaties, but Fertig had a secret weapon.

Salipada Pendatun had reason to expect that his American foster father would help him obtain the American recognition and support that he deserved. But Edward Kuder, the man who reportedly could never refuse his foster son, was so focused on the maintenance of American authority that he discounted Pendatun’s accomplishments. Instead, Kuder wrote Pendatun letter after letter instructing him to “submit” to Fertig.

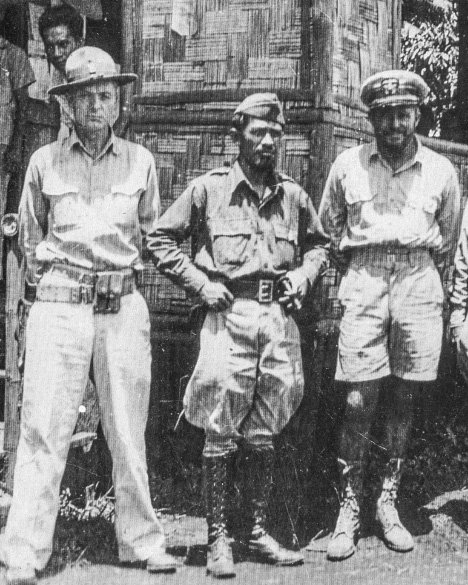

Salipada Pendatun (center) with American emissaries, 1943 (Source: The MacArthur Memorial)

Finally, at the request of his own men, who were worried about not receiving their back pay, Pendatun complied. Wendell Fertig immediately transferred and demoted him, and Pendatun spent the rest of the war in relative obscurity. The remarkable accomplishments of Salipada Pendatun, a young guerrilla leader with exceptional talent and charisma, were never properly recognized by Fertig, MacArthur or, for that matter, Edward Kuder. He was the first and most effective guerrilla chief of Mindanao but was denied an equal opportunity to excel at war.

Freedom Fighters and Foreign Aggressors

In the first grim year of the Japanese occupation, while American fugitives on Mindanao were stunned, scattered, and disheartened, the Moros, on multiple fronts, fought the occupiers with astonishing results. However, their deeds were mostly absent in the postwar memoirs of American wartime resistance written by Wendell Fertig and others.

For 80 years, the stories told of the Mindanao guerrilla movement, the largest in the Philippines, have been mostly about the few Americans who avoided or escaped Japanese prison camps and took leading roles in the armed resistance. The full story of the fight for Mindanao is a David and Goliath tale that prefigures the current struggle in Ukraine. In that forgotten history, it was Moro freedom fighters who did most of the fighting and made most of the sacrifices, and it was they who achieved the most improbable and inspiring victories against the occupiers of their homeland.

Thomas McKenna is an anthropologist and the author of Moro Warrior, a true story of the Moro guerrillas of World War II. He has been conducting research and writing about the culture and history of Philippine Muslims in Mindanao since 1985. He currently lives in San Francisco.