That Strange Writing in Philippine Passports

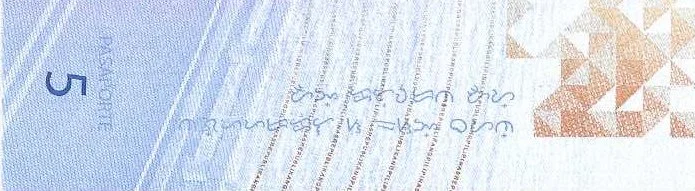

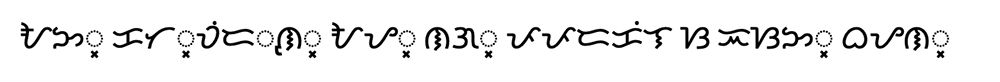

/Baybayin on the pages of the Philippine Passports

This might amaze those who’ve struggled to secure visas for Japan, Europe, Australia, or the US, among other popular destinations that often treat Filipino visa applicants with suspicion. Otherwise, why would embassies demand details like the size of your bank account or the amount of property you own?

Even with a visa, many Filipino travelers can attest that suspicion extends to the immigration counters of these selective destinations.

Imagine a particularly inquisitive or rude immigration officer somewhere noticing the Baybayin script in our passports and asking, “What does that say?”

Yes, there is Baybayin printed on our passports — not just on one page, but throughout. An entire sentence in this Filipino native script appears on nearly every odd-numbered page. It’s faintly printed, like a security mark, so you might not have noticed it.

If you can’t read Baybayin, it’s easy to overlook it as so much gibberish.

But what if that immigration officer does ask you to explain what the Baybayin says as a way to challenge or test you? After all, your passport could be fake, or you could be someone posing as a Filipino. Surely every Filipino must know how to read their own script, the officer might think.

In that nervous moment, you’d have at least two choices: you could admit that you don’t know, which might lead them to doubt your identity; or you could lie and offer a fabricated translation, such as “every drug user in the Philippines can be killed extrajudicially.” But that would be perjury, especially if the officer already knows the correct translation.

The best option would be to proudly tell the truth and explain what it says in Filipino, as it’s written in Baybayin:

Or in Roman script:

"Ang Kat’wiran ay nagpapadakila sa isang bayan."

My personal translation: "Reason is what elevates a nation."

However, according to the Wikipedia entry on the Philippine passport, this statement in Baybayin is said to be a translation of the Biblical proverb (14:34), “Righteousness exalts a nation.”

As a journalist, I know better than to cite Wikipedia as a source, but no one I’ve spoken to at the Department of Foreign Affairs seems to know the origin or intent of the Baybayin in our passports. Strangely, the Wikipedia entry didn’t cite a source either. Searching the DFA website has led to no further clues.

The statement itself doesn’t seem to indicate that it’s inspired by the religious proverb. Without confirmation, and in line with my own belief that a secular state should avoid printing explicit religious messages on government documents, I’ll go with my own translation: “Reason is what elevates a nation.”

Not only can “Kat’wiran” mean both “reason” and “righteousness,” but I believe my translation more closely reflects the values this nation was founded on.

The power of human reason was José Rizal’s main argument when he defied the church’s demand that he retract and submit.

This year, I finally read the remarkable correspondence between Rizal and his former Jesuit teacher, Father Pablo Pastells, during Rizal’s exile in Dapitan.

Pablo Pastells (Source: Facebook)

Pastells took it upon himself to convince the “filibustero” (which, in today’s language, would be a "terrorist") to abandon his revolutionary ideas about the rights of the native population and submit to the authority of the church.

Rizal’s response was clear: science and the human capacity for reason were greater evidence of God than any holy book. Following one’s conscience, rather than obeying what he believed was wrong, was as much an act of faith as accepting religious sacraments (which is why he was never allowed to marry Josephine Bracken in church).

Rizal’s philosophy championed the sovereignty of reason as a guiding force for reform and enlightenment, rejecting superstition and unquestioned authority, particularly from the Spanish colonial regime and the Catholic Church.

In the end, Rizal and Pastells agreed to disagree, with Rizal declaring in one of his final letters that he had "seen a little light, which I simply want to share with my countrymen."

Rizal trusted that our capacity for reason — and not mindless obedience to religious authority — would lead us to righteousness and, ultimately, justice.

Imagine a particularly inquisitive or rude immigration officer somewhere noticing the Baybayin script in our passports and asking, “What does that say?”

All of this, of course, is a long riff on that short line in our passports. Whatever its original intent, it’s loaded with meaning.

I’m still curious, though: why express this idea in a native script that so few Filipinos can understand?

It feels a bit like performative nationalism, a way to show the world that, like many Asian cultures, we too have our own writing system, even if most of us weren’t taught how to use it.

Or perhaps a decision-maker liked the idea of promoting sovereign reason but felt uneasy about its subversive potential. After all, Rizal died for his stubborn beliefs.

Reason over robotic obedience can be dangerous in any era. Put it in the passport but hide it behind what’s essentially a secret code.

But now that we know, we can own it.

And you’ll know what to say when an immigration officer or anyone else asks about that strange writing in your passport:

"Reason is what elevates a nation."

Then hold your head high as they wave you through.

First posted in:

https://www.gmanetwork.com/regionaltv?fbclid=IwY2xjawNRTghleHRuA2FlbQIxMABicmlkETFTa1R4WmVCajZORllWeWxwAR5tJGHE9GBVG-MTLw21t7O9M38qtg03MYifjiCAdA5noHqBZX71NkyVqPVbyA_aem_T_fMf5u5ZGstaEb_W3zbtQ/