Shackled Art

/Peace Wall by Alan Jazmines

Because they were seen to pose a greater danger to the dictatorship and the oligarchy it represented, they suffered more than what many common criminals experience, being subjected to the most degrading forms of torture and abuse, even “forced disappearance” or “salvaging”—code words for summary execution. However, the end of the Marcos regime did not mean the end of political repression.

While the first Aquino regime released some high-profile political prisoners like Communist Party of the Philippines founding chairman Jose Maria Sison, many others remained in detention, and counter-insurgency campaigns continued. Succeeding regimes, from Ramos to Aquino III, continued the policy of detaining activists and members of the revolutionary movement. The two regimes before President Duterte’s were never serious in continuing the peace process with the Left, let alone discontinuing harsh counter-insurgency measures that included “forced disappearances” and incarceration.

Portraits by Voltaire Guray

In many political prisons in the world, one of the most important activities of detainees is the creation of art works. Physically isolated from the resistance movement, detainees have been known to engage in cultural work inside prison, including the production of art works whereby their advocacy finds expression, boosting and enriching their spirit of defiance. Art becomes another vehicle for their political struggle. Paintings, sculptures, prints are some of the artworks produced in prison, implicitly or explicitly projecting political messages.

Philippine political prisoners exhibited their art works recently at the Bulwagan ng Dangal of the UP Main Library, through the efforts of Samahan ng Ex-Detainees Laban sa Detensyon at Aresto (SELDA), Karapatan, Hustisya, Desaparacecidos, and other human rights groups. Many of the works in the group show entitled Sa Timyas ng Paglaya are searing portrayals not only of the brutish physical condition of incarceration on unjust grounds. They are also expressions of their unrelenting critique of the System, which brings about oppressive social conditions that breed resistance, which in turn invites repression that uses prison to silence and punish political protest.

Among the prison artists represented are well-known Left personalities such as Alan Jazmines (also a poet whose works have been published in the Philippines and abroad) and Tirso Alcantara, who specializes in handicraft made from found objects. The other artists are Rene Boy Abiva, Sandino Esguerra, Renante Gamara, Maricon Montajes, Billy Morado, Hermogenes Reyes Jr., Gerald Salonga, Eduardo Sarmiento, Eduardo Serrano, Randy Vegas, JP Versoza, Rex Villaflor, Ruben Rupido, and Voltaire Guray, the last being the most prolific. Imprisoned for four years and recently released on bail, Guray is a youth activist of Anakbayan, a peasant organizer and former member of the Graffiti Art Ensemble, Sining Obrero, as well as music bands Renegades and Student Genre.

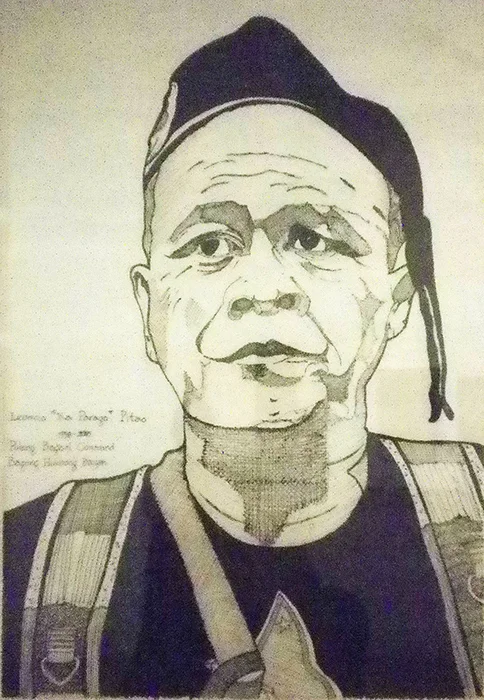

Ka Parago by Ruben Rupido

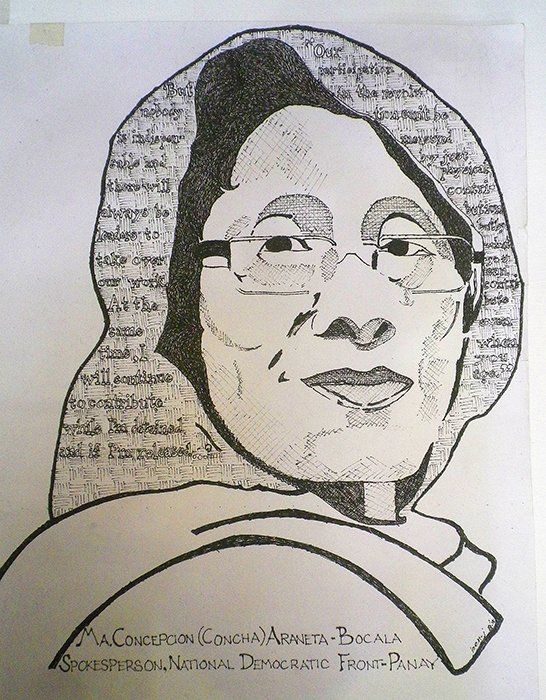

Concha Araneta-Bocala by Ruben Rupido

The printed program describes the objective of the exhibit: “Sa Timyas ng Paglaya ushers in a renewed campaign by various human rights organizations and advocates to free all freedom-loving Filipinos held captive in the various jails in the country. In light of President-elect Rodrigo Duterte’s pronouncements to release them, we welcome the bright prospects of freedom for all political prisoners. Taking off from what timyas means, which is genuineness or purity, the exhibit probes into the authenticity of our country’s freedom even as it bolsters the campaign to free all political prisoners in our midst.” And here are excerpts from the insightful curatorial notes of Professor Lisa Ito of UP, entitled “Creativity Within Captivity”:

“This is an exhibition of works produced in the most unlikely of spaces and circumstances: inside the confines of cells and prisons throughout the Philippines, where 543 political prisoners are currently held captive by the state. The makers are all activists: arbitrarily arrested, detained, and facing either political or false criminal charges for their long-term, often lifelong, work in community organizing among the poor.

“Sa Timyas ng Paglaya gathers around 130 objects made by such political detainees. Retrieved from prisons and personal collections throughout Manila, Cagayan, Batangas, Bicol, and Samar, the paintings, handicraft and poetry on display embody a wealth of stories about the struggle within and against captivity, on both personal and collective scales.

“The act of making is also a cathartic gesture and a telling of histories held dear: a means of remembering and tangibly connecting to places, people and ways of living suddenly cut off by the state of captivity. One encounters a father’s pencil sketches of his daughter; portraits of comrades and the masses sorely missed; or vistas of the rural countryside which is both beloved home and frontier of the struggle for emancipation.

Dark Room by Voltaire Guray

“Finally, their act of making is also an extension of dreaming about a better world and how it might look like in this incipient stage. This is a quality embodied even by the humblest of works in the exhibit. Images of both fallen and present revolutionaries point to the depth and breadth of sacrifices made in the struggle for liberation; while painstakingly produced crafts, such as beadwork with political themes and paper models of spaces and ecologies within a more communal vision of society, mirror the equally painstaking and patient process needed to build the structural foundations of change.”

Prison art, which became a popular cultural activity behind bars during the martial law period, continues to thrive in the hearts and hands of Philippine political detainees, with their fervor ever burning, so to speak.

First published in The Philippine Reporter of Toronto, Canada: http://philippinereporter.com/2016/08/19/art-as-resistance/

Ed Maranan has won major literary awards for his poetry, fiction, essays, plays, and children's stories. He writes a column for The Philippine Star, contributes to other publications, and is a member of the Baguio Writers Group, PEN Philippines, and Umpil (Writers Union of the Philippines). He was a political detainee for more than two years during martial law.

More from Ed Maranan