Salting the Filipino Palate – The Rufina Patis Story

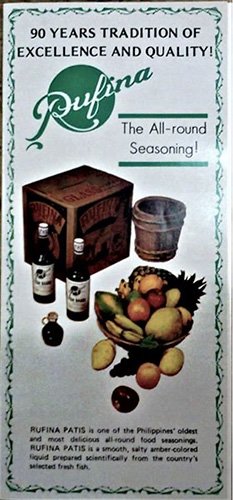

/Rufina Patis ad (From the collection of Jose Victor Torres)

You need patis to enhance flavors in dishes like sinigang and, mixed with calamansi, nilaga. A few drops can make a simple dish into a ooooh-so-good. It is also used as a dipping sauce for sour fruits like green mangoes in place of salt. It’s also used as a salt substitute in some recipes. (an apocryphal story goes that patis is the secret ingredient of a popular fried chicken brand). Another story goes that one popular actress always asks her alalays (sidekicks) to make sure that her meals came with a bottle of patis.)

Patis is not uniquely Filipino. It is Asian. We share the use of patis (nuoc mam) with the Vietnamese. It is created through the fermentation process of preserving fish by packing it in salt.

(While on a trip to Malabon with historian Ambeth Ocampo and the grandson of Rufina Patis' founder, Ramon Lucas, back in the 1990s, we visited one of the small places where patis was being fermented. The smell of the place, of course, was unimaginable. Concrete vats with wooden-board-and-galvanized-iron lids held gallons of fermenting fish. One could only imagine what the contents looked like. A journalist friend of mine who did a small segment on TV on the making of patis told me that it was a good thing I didn’t look inside a vat.

“Isang tingin ko lang, ayaw ko nang tumikim ng patis (Just one look and I didn’t want to taste patis anymore),” he told me, grimacing. But when I asked Lucas about it he said that my journalist friend apparently saw the old way the fermentation was done. Today, for the better brands, the process is more sanitary. In fact, you can tell by the quality of the patis how it has been stored – a poorly-made sauce starts to leave traces of salt crystals.)

Patis was already known to early Filipinos. The word is found in the 1860 Noceda y Sanlucar vocabulario, defining it as a caldo de salmuera or "salty brine." There is no mention of the how it was made.

Rufina Patis is a popular brand that has been with us for over a century. Who knew this brand of fish sauce was the brainchild of a simple housewife who would turn a P50 capital and a few earthen jars into a million-peso industry.

The Rufina Patis brand was the creation of Rufina Salao vda de Lucas, a tuyo and tinapa vendor from Malabon (then part of Rizal Province). In the 1900s, Malabon was a small seaside town north of Manila whose natives relied on fishing for a living. Since fish was abundant during the summer season, Lucas found an inexpensive way of preserving her stock since refrigeration was then unknown in the environs. The preservation involved turning the fish into bagoong (fish paste) – mashing the fish with salt to be put in earthen jars to ferment. It was while tending these jars that Lucas discovered a liquid that was clearer than the bagoong. After a series of experiments in her kitchen, she managed to extract the juice which seems to enhance the flavors of native dishes. Lucas has “discovered” patis.

Rufina Salao vda de Lucas (Photo courtesy of Isidra Reyes)

She began selling bottles of the liquid in the local market. Soon it became popular among her townmates and, later, in various town and cities. She then improved her patis by replacing the earthen jars with wooden barrels which filtered much of the impurities of the patis. In 1945, she replaced these barrels with concrete vats.

As demand for patis named after Rufina grew, the Lucases set up their first processing and bottling plant along C. Arellano Street in 1957. Soon, her patis brand was being exported, aside from its growing popularity in local homes and restaurants. In 1958 her son, Jesus, went to the United States and saw the huge sales potential for the sauce among the Filipino communities. The product passed stringent US government food standards before it was given permission to be sold on the American market. Ten years later, the company opened a second processing and bottling plant along Bonifacio Street.

Lucas died in 1961 But her industry continues to grow as a family-managed business.

Posted with permission from the author’s Facebook post.

Historian, essayist, freelance magazine writer and an award-winning playwright, Jose Victor Z. Torres is an associate professor of the History Department at the De La Salle University-Manila (DLSU-Manila) and Associate Director for Drama and History at the Bienvenido N. Santos Creative Writing Center also in DLSU.