Remembering the ‘Brain Man’

/Book Review: The Brain Man Dr. Victor Reyes: A Daughter’s Memoir by Elizabeth V. Reyes

A self-made man born and raised in relatively humble circumstances, he reached the highest ranks of his profession as early as the 1950’s and became known in his time as “the best cranioplasty surgeon in the world.” In 2005, the University of the Philippines gave him its highest honor by naming him “Builder of Medicine.”

Raised by a single nurse-mother, Marta Concepcion, in prewar (“Peacetime”) Manila, he accompanied her on her rounds. She mentored him towards success through academic achievement, frugality, and a laser-beam focus. As recounted by eminent war historian Alfonso Aluit, Dr. Victor Reyes attended to bloodied victims of war at the Philippine General Hospital on 20-hour shifts while Manila burned and exploded around them. His graduating medical class of 1943 was among those chosen in 1945 by the U.S. government to obtain training in Boston Brahmin schools of the East Coast.

Having placed 7th in the Medical Board and topped the exam for the scholarship among the candidates, he would spend the next six years specializing in neurosurgery in the United States and in Canada. Upon his return to Manila, he would continue his association with the PGH, which would last nearly four decades.

Dr Reyes in the largest office in PGH. The surgeon and his longtime secretary Mila Bayaton receive dignitary patients from Papua New Guinea.

Just before his trip to the United States, he met and married the winsome nurse Edna Fernandez, with whom he had five children, the eldest, Elizabeth, being the author of this memoir.

She recounts Dr. Reyes’ impressive rise to glory and his multifaceted personality. Not only was he a topnotch doctor, he was also an indefatigable traveler, amateur artist, art collector, keen photographer, and bike aficionado. A true Renaissance man.

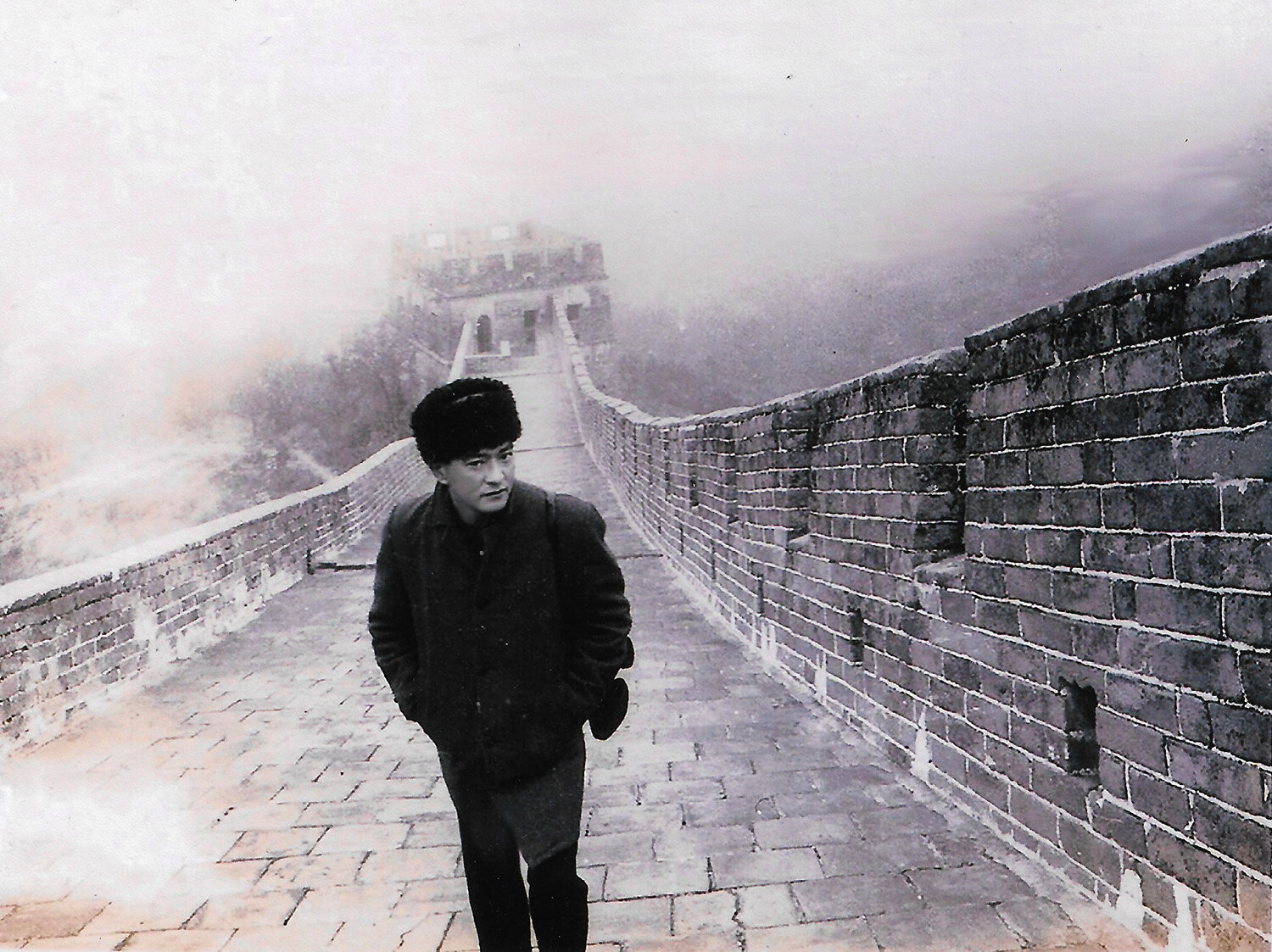

Dr. Reyes at the Great Wall of China

Dr. Reyes with Baguio artists

Among his cultural heroes were Hippocrates and Leonardo da Vinci. Another side to him was his idealism inspired by Dr Albert Schweitzer, whom he sought out and actually met, and spirit of service to indigent patients.

Dr. Victor Reyes and Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man, 1994. When visiting the town of Vinci in Tuscany, Dr. Reyes stepped right up to the giant sculpture of Leonardo’s man within a globe --and posed with arms akimbo, feeling larger than life.

Dr. Reyes’ Clinic in Philippine General Hospital . After Reyes’ historic visit to the village hospital in Lambarene in Africa, the surgeon returned to PGH Manila, where he was watched over by his medical idol, Dr. Albert Schweitzer.

“The Brain Man” turned out to be a ten-year project due to the desire of its author for a thorough, insightful, and definitive work on her father. Liz Reyes describes the book as evolving from a simple biography to an anthology to a daughter’s memoir.

Dr. Victor Reyes was a complex personality who had varying contradictory effects on his colleagues and friends; on the one hand, admiration and awe at his talents and, on the other, fear from his students and even vigorous opposition and criticism from peers opposed to his approaches to academic and medical training. Dr. Reyes’ star quality was reflected in his looks; his daughter admiringly compares him to Gregory Peck and says that his family may have been related to the actor Leopoldo Salcedo, with whom he bore more than a passing resemblance.

Even his own immediate family seemed not to fully comprehend him, being insulated from the inner workings of his profession and the elite circles that provided some of his most devoted and cherished clients. Among families and individuals that he served and cultivated were the Ysmaels, Chiongbians, Rufinos, Laurels, Ledesmas, Jalandonis, publisher Hans Menzi, and Senator Jovito Salonga.

Among his many admirers were Hilarion “Larry” Henares, Justin “Tiny” Nuyda, Grace Katigbak, Dr. Gloria Aragon, Dr. Antonio Rafael, Dr. Gerardo “Gap “Legaspi, Dr. C.J. N. Posoncuy, former UP President Francisco Nemenzo, Louis Jurika, former First Lady Amelita “Ming” Ramos, and Bobby Manosa.

In turn, among his favorite characters who availed of his services were Rosa Rosal, Eva Estrada Kalaw, artists HR Ocampo, Vicente Manansala , Solomon Saprid, former First Lady Imelda Marcos and Lorna Laurel. “They were,” says Liz, “part of his own magical circle that he kept largely to himself.”

Dr. Reyes was also a medical celebrity, with the same kind of cachet in the Philippines that Dr. Christian Barnard would have internationally in his own field. Indeed, in an open forum attended by Dr. Barnard, he challenged the latter on the attention given to the heart when in his opinion, the brain had preeminence in its complexity and importance for the whole body. Prominent as a display in his home was a bottle with a brain. He could be said to have had a cerebral, Einsteinesque approach to life.

Edna Hernandez Reyes, his wife, referred to her husband as “Dr. Reyes” and “Number One.” The family acknowledged that they lived separate lives for decades and only came to reconciliation in the last months of his life. For advice on social interaction with her schoolmates, Liz Reyes was told to “ask her father” what her mother regarded as a moral issue. “Dad made the family decisions,” recalls Liz, “but left the daily caretaking to my mother, Edna, and the yayas (nannies).”

Liz writes:

“We all existed in my father’s big shadow and my mother did as well. After the brilliant young doctor had found his nurse-wife in his alma mater PGH, she gave up nursing and became the devoted housewife and mother to us five children. But Mom could not be the full ‘partner’ that Victor Reyes sought out in every interesting (often cerebral) person he met in his bigger medical and social world.”

The family straddled the divide between the Filipino and American worlds, which the parents both admired and profited from. As the eldest, Liz was the first to confront the many contradictions of this conundrum. She recounts being the first among the children to have an identity crisis. Was she Filipino American or American Filipino? While qualifying for the school cheering squad as the only Filipino, she was cast as a hillbilly in pigtails on a Sadie Hawkins Day at school. All of this happened in 20th century Manila.

Although Liz was sent to the American School in Manila, she could not date anyone without a chaperone. This education prepared her for an American university but, since it had been decided that Liz should follow in her father’s career, she was enrolled at the University of the Philippines for Zoology, preparatory to a medical degree.

After a year floating in this unfamiliar world of the local Filipino, she was transferred by her father to an American university in the Northeast with extreme winters and roommates indifferent to her plight. For a while, she wondered if she was “manic-depressive.” While struggling with her Filipino and American identities, she finally rejected the path to becoming a doctor and found her groove as a Journalism major. Her father had envisioned her as a future doctor, calling her “his best Bet,” but writing was to prove her career track.

This possibly explains why this book is a daughter’s memoir rather than a collective family one since it was Elizabeth who emerged as the writer among her four siblings. Brother Norman also became a doctor like his father (whom he held in awe; he also feared being called “stupid” by him) while Mellissa married a doctor, Danilo Gervacio, who had been one of her father’s students. He too trembled under his future father-in-law’s interrogations.

Having experienced deprivation himself, Dr. Reyes as UP Regent stressed health care delivery to the poorest patients at PGH and other communities instead of handling them like “guinea pigs” in a teaching and training center.

One of his main accomplishments was setting up the UP PGH Central Block, which modernized its facilities and practice. This served him well when he was replaced by younger specialists who had a different approach and orientation. Retreating to the role of professor emeritus and Assistant Director for Health Operations, he learned to be more humble (he had been described by peers as “temperamental and conceited” and “acting like a demi-god and a diva”) and to work with people as equals in this new administrative role.

Dr. Reyes at PGH during Martial Law in the 1970s

Dr. Reyes would see his children have their own successful lives in different professions. His wife, Edna, would finally fulfill her dream of settling in the United States with one of her children, a move Dr. Reyes had resisted due to his devotion and loyalty to the Philippines. At age 54, his writer-daughter Elizabeth would finally find her life partner in Hans-Juergen Springer, a German banker with the Asian Development Bank. Her mother “genuinely liked this conventional (well-dressed) banker” even if he was German. “Her prayers were finally answered. It was the first time Mom ever showed her smiling approval for a man I brought home,” writes Liz.

Dr. Reyes saw his biggest challenge towards the end of his life, when he was diagnosed with Stage 4 Lymphoma. The family assembled in daughter Mellissa and son-in-law Danilo’s Maryland home and kept the parents company while Dr. Reyes received chemotherapy. The philosopher and writer in him abided by Dylan Thomas’s words: “Rage, rage against the dying of the light.” He still wished for “a little more time” because so many new and exciting developments were emerging in medical science.

The family decided to take him back home to his Makati home in the Philippines where he could still meet old friends such as Jovito Salonga and see his self-built rest house in Tagaytay. He passed away peacefully in a hospital, surrounded by his loved ones on March 6. As the eldest child, Liz Reyes signed the hospital form acknowledging his death.

Liz Reyes ends with these words:

“I don’t feel that his story is finished. Maybe it will never be. In a funny way, this book gives Dad what he always wanted: a little more time in this world.”

A career diplomat of 35 years, Ambassador Virgilio A. Reyes, Jr. served as Philippine Ambassador to South Africa (2003-2009) and Italy (2011-2014), his last posting before he retired. He has written and edited six books, including Gloria: Roman Leoncio’s Kapampangan Translation of Huseng Batute’s Poem-Novel (Center for Kapampangan Studies, 2003) given the National Book award in 2004; In the National Interest: The Philippines and the UN: Issues of Disarmament, Peace and Security, 1986-1991(NY and Manila, 1991); La Revolucion Filipina, 1896-1898, El Nacimiento de Una Idea (Santiago de Chile, 1998); Nuestro Perdido Eden: A Novella on Manila (Ateneo de Naga Press, 2019); A Memory of Time collection of essays (Quezon City, 2020); and We Remember Rex@100 (Quezon City, 2022).

More articles by Ambassador Virgilio Reyes, Jr.