Remembering Our Manongs and the Delano Grape Strike

/For many California growers the Filipino was their primary worker, actually favoring the Filipino worker over any other worker for several reasons. There are many skills to be learned in working in the fields, and the growers knew the Filipino was already a very experienced worker who required no extra training. So the growers found the Filipino worker to be very convenient: he was single, he was experienced, he was cheap to maintain, and he was always available. To the grower, this was important, because it meant higher profits for him. This created, however, a unique predicament for the Filipino. He was a prized worker for the grower, but at the same time he was ready to be organized and to struggle for his rights.

- Philip Vera Cruz, labor leader

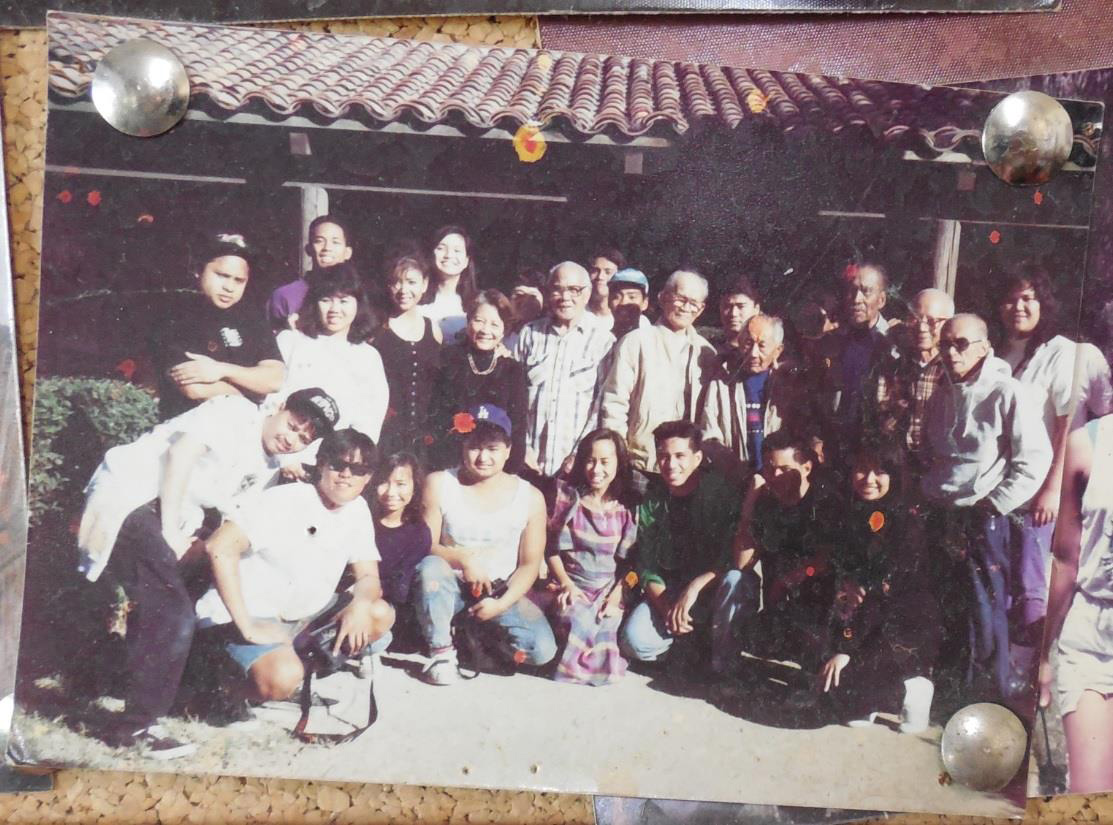

UCLA Samahang Pilipino and CSULB Pilipino American Coalition with the Manongs at Agbayani Village, 1990 (Photo courtesy of Mark Pulido)

The Filipino men who worked in the fields were mostly elderly, having immigrated in the 1920s and 1930s in search of the American Dream. The men were American "nationals," not American citizens when they first arrived. Faced with a panoply of racist and discriminatory laws and practices (unable to own land, vote, become citizens, marry Caucasians, be hired for some jobs, live in some neighborhoods, and worse) they survived. They became heroes as members of the First and Second Filipino Regiments of the U.S. Army during WWII. Some of men who fought in the Philippines brought back "war brides" to the U.S. and started families. Many returned to the same fields they had worked for years, as migrant laborers following the crops from Southern California up to the Pacific Northwest and beyond. They planted, harvested and packed every kind of fruit and vegetable grown at the time: apples; peaches; oranges; strawberries; tomatoes; lettuce; spinach; beets; corn; cotton; hops; asparagus. They also picked grapes.

Herb Delute is a second-generation Filipino American. His family lived in Delano in 1965. Like many children and teens, he worked in the fields with his parents and other siblings. Herb described the harsh working conditions of his childhood:

“Farm workers were paid well below minimum wage. Working under the hot sun, they had no breaks, no water, and no bathrooms. They worked eight to ten hour days, six days a week…You could be working and in the next field the growers would be spraying Malathion [an insecticide]… When the season was over, there were no more work and no unemployment benefits.”

Although conditions were dangerous, there was no recourse for workers. There was no one to hold growers accountable for their treatment of the workers. There were also no healthcare benefits and no medical facilities available. No unemployment benefits when harvest was complete meant that the workers had to keep moving, following the crop cycle to find work.

The leader of the Filipinos who started the Grape Strike was Larry Itliong, who immigrated to the United States in 1929. Within a few years he was organizing cannery and agricultural workers. Ray Paular, an octogenarian now living in Sacramento, started working in the fields when he was 12 years old. He worked alongside the older Filipino men, his manongs. He knew Larry Itliong from Trinity Presbyterian Church in Stockton, which they both attended. He tells a story about the summer of 1944, when he worked with Itliong as a member of his crew. Paular and two other teens from Stockton went to a farm in Biola, California, to pick grapes. However, by the time they arrived, the bunkhouse was already full. The latecomers had to sleep on top of grape boxes outside, right next to the pig pen. Paular remembers thinking that the pigs had a roof over their heads, but the three of them were sleeping under the stars. Substandard living quarters for workers were the norm at most farms. Larry Itliong and others worked to change such conditions. Of Itliong, Paular reminisces: "Larry was a likeable guy. Publicly, he had it all together. Certain people have the magnetism to draw people together. He had that kind of personality. I looked up to him."

By 1965, Larry Itliong had more than 30 years experience organizing workers and leading strikes. He was head of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), affiliated with the AFL-CIO union. That summer, the AWOC had a successful strike against grape farmers in Coachella. There, the workers won a pay increase to $1.40 an hour. As the Filipinos moved up into the Delano area to pick grapes, they found growers were only paying wages at $1.10 an hour. On September 7, 1965 in the Filipino Community Hall in Delano, members of the union voted to strike for better wages and working conditions. The next day, the Grape Strike began. The elderly Filipino strikers met violent resistance from the growers, who had local law enforcement on their side. They were evicted from their homes in the labor camps on the farms and brutalized on the picket lines. The Filipino community rallied to organize picket lines and help feed and shelter the displaced workers. Mexican workers were used as scabs to cross picket lines, in the usual practice of using one ethnic group to break the strikes of another. Itliong and other Filipino leaders convinced Cesar Chavez, then leader of the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA), which was predominantly Mexican, to join them. On September 16, 1965, the NFWA joined the Grape Strike. In 1966 the AWOC and NFWA merged to form the United Farm Workers Union, with Chavez as director, Larry Itliong as assistant director and Dolores Huerta and Philip Vera Cruz as vice presidents. The Grape Strike and ensuing international boycott of grapes lasted for five years, ending in 1970 with most farmers signing contracts with the UFW, and getting better pay, improved working conditions and benefits.

Filipino Communty Hall (Photo courtesy of Gloria Perlas Pulido)

The victory changed the dynamics of the Filipino community. The ability to collect unemployment benefits when harvest was over meant that families could now stay in Delano. Herb Delute maintains that family life got better for workers. Children of farm workers were able to attend college. Workers realized that there were other doors for employment. Delute’s mother left the fields and found a job at a cannery. A medical clinic was built—staff there saved the life of one of Delute’s friends. Delute and other children of some of the original strikers, is a founding member of the Filipino American National Historical Society’s Delano Chapter, which describes the impact of the Grape Strike:

“[T]he strike raised global consciousness about the plight of farm workers. It was a pivotal moment in which Filipino Americans made their largest and most significant imprint on the American narrative. That bold step taken by these Filipino workers—most of whom were senior citizens in the twilight of their lives—inspired labor movements and movements for civil rights and social justice among Filipino Americans and Americans of all backgrounds.”

Agbayani Village is a retirement community in Delano built for elderly Filipino workers in the 1970s by UFW supporters and volunteers. It was named after striker Paolo Agbayani, who died on the picket lines. Activist Marissa Pulido Rebaya visited the manongs of Agbayani Village for the first time in 1990. She states that first visit was "the best thing that ever happened to me." Meeting manongs and their grown children and learning firsthand about their lives and the farm worker movement made a profound impact on her life. Rebaya visited Agbayani Village often, with groups of college students. However, she noted that after all the manongs at Agbayani Village passed away in the mid-1990s, college student groups eventually stopped visiting. In 2004, to commemorate the centennial of Philip Vera Cruz's birth, Rebaya and her brother Mark Pulido (currently mayor of Cerritos, California) established the Agbayani Village Pilgrimage Organizing Committee. Rebaya says:

“We felt a need and purpose to organize trips to Agbayani Village and Delano, just like we did when we were students at UCLA in order to educate others and preserve the Manongs’ legacy. We call these trips ‘pilgrimages’ because Agbayani Village, Filipino Community Hall in Delano, the September 8, 1965 Grape Strike, and the Filipino American Farm Worker Movement collectively comprise one of the single most important ‘touchstone’ moments in history that started ‘The Filipino American Movement’ overall. In my opinion, the Delano Grape Strike symbolizes the true power of our Filipino community. It represents the greatness we have accomplished in the past and what we are capable of now and for the future. This goes beyond the ‘Bayanihan Spirit’ of working together to include: Struggle. Resistance. Sacrifice. Organizing [and] Unionizing. Coalition building. Fighting for justice. And ultimately, the ability to lead social movements and to achieve political empowerment.”

Rebaya is concerned not only about the lack of awareness of the role that Filipinos played in the Grape Strike, but also “serious attempts by others outside of our community to revise history, minimize, and even erase the Manongs’ historical role.” A recent example is a 2014 feature biopic of Cesar Chavez, which ignores the role played by Filipinos in the Strike and in the farm workers movement. Larry Itiliong’s role is severely diminished. Perhaps most egregious, scenes based upon actual photographs from the Strike were reproduced in the film without the Filipinos.

One of Larry Itliong's children, Johnny Itliong, is working tirelessly to gain recognition for the achievements of his father and the role of Filipinos in the farm worker movement. Johnny Itliong lists his father’s impressive resume of founding unions and organizations, writing farm labor laws, which formed the basis of laws still in existence, and his community activism. Johnny confronted one of the filmmakers of the Chavez film about the distorted history depicted in the film. He was told, “That’s Hollywood.”

Johnny Itliong in front of Delano mural depicting his father, Larry Itliong (Photo courtesy of Johnny Itliong)

Johnny believes the biggest lesson of the Grape Strike is what can happen "when people are working together, crossing the racial barrier, setting differences aside and working collectively." He would like his father's contributions to civil liberties and labor organizations in the United States and the Philippines to be acknowledged. He emphasizes, "This is not about denigrating Cesar Chavez. Cesar was my tio. I just want to set the record straight."

To rectify the lack of general knowledge of Filipino involvement in the Grape Strike and farm worker movement Rob Bonta, California Assembly Member from the 18th District, in 2013 sponsored AB 123, a bill requiring the State Board of Education to include instruction on the role of immigrants, including Filipino Americans, in the farm worker labor movement in California. This year he also sponsored AB 7, a bill to establish a special day of recognition for Larry Itliong, whom he describes as "a California hero." Both bills passed the Assembly and were signed into law by Governor Brown.

A documentary, “Delano Manongs: Forgotten Heroes of the United Farm Workers” by Emmy-award winning director Marissa Aroy, has been screened to acclaim at venues around the country and aired on PBS. Filipino community activists organized to have a school in Union City, California, renamed Itliong-Vera Cruz Middle School this year. Filipino American National Historical Society chapters around the country will celebrate October 25th as Larry Itliong Day, part of Filipino American History Month events. In San Diego, on the Filipino American Highway, State Route 54, an overpass will be designated The “Itliong-Vera Cruz Memorial Bridge.”

Larry Itliong by poster of his father, Larry Itliong for “Delano Manongs” film (photo courtesy of Marissa Pulido Rebaya)

When discussing the legacy of the Grape Strike and its leaders, Ray Paular says that Larry Itliong's legacy is that he "left footsteps to follow--but the struggle is not really over yet." Paular declares that Larry Itliong Day is "a long day in coming."

Ray Paular (Photo courtesy of FANHS- Sacramento Delta chapter)

Herb Delute contends, "The Filipinos are the ones that took the risk. They are the ones that organized. They are the ones that went out and set the stage for improvements for what happens today in the fields. Bathrooms. Breaks. Recourse against the growers."

Marissa Pulido Rebaya agrees, "It is important to remember the Delano Grape Strike so that we can educate others and preserve the Manongs’ legacy. The Manongs made significant contributions to U.S. Labor History, in particular the Farm Worker Movement. And as a result, they made a huge and glorious impact on civil rights and social justice in America."

References:

Filipinos: Forgotten Asian Americans by Fred Cordova. Kendall-Hunt Publishing, 1983.

Excerpt from Philip Vera Cruz: A Personal History of Filipino Immigrants and the Farmworkers Movement by C. Scharlin & L. Villanueva. Published by UCLA Asian American Studies Center and UCLA Labor Center, 1992.

Interviews and correspondence with Herb Delute, Johnny Itliong, Marissa Rebaya Pulido, & Ray Paular, September, 2015.

United Farm Workers website: www.ufw.org.

Marissa Pulido Rebaya, member of "Historical Legacies and New Activism" panel at "BOLD STEP: A Celebration of the 50th Anniversary of the Delano Grape Strike" sponsored by the Delano Chapter of the Filipino American National Historical Society. September 5, 2015 at Robert F. Kennedy High School in Delano, California. www.youtube.com/watch?v=wUy0qWdjnzQ

What the new Cesar Chavez film gets wrong about the labor activist. By Matt Garcia. Smithsonian.com. April 2, 2014.

Assembymember Rob Bonta website: asmdc.org/members/a18/

“Delano Manongs: Forgotten Heroes of the United Farm Workers” by Marissa Aroy. 2014 www.delanomanongs.com

Filipino American National Historical Society, San Diego chapter website: fanhs-sandiego.org/itliong-vera-cruz-memorial-bridge

Filipino American National Historical Society, Delano chapter press release for BOLD STEP conference distributed on August 5, 2015.

Itliong/Vera Cruz Coalition website: sites.google.com/a/nhusd.k12.ca.us/the-itliong-vera-cruz-coalition and New Haven School District website: www.nhusd.k12.ca.us/taxonomy/term/10

Linda Revilla, PhD, taught Filipino and Asian American studies for 20 years. She is a former trustee and lifetime member of the Filipino American National Historical Society.