Ramon Reyes Lala and the Worlds He Bridged

/Ramon Reyes Lala (Source: Cambridge University Press)

For the next two centuries Manila galleons stitched Asia to the Americas, carrying silk and porcelain eastward, silver westward, and always island sailors below deck. Many died, some deserted in Acapulco, and a few drifted north into California’s mission world. In Louisiana, fishermen from Manila built stilt villages like St. Malo, drying shrimp for New Orleans markets until hurricanes swept their homes away. Others signed aboard New England whalers, rowing into freezing spray and boiling blubber in tryworks that smoked for miles. A handful even marched in Union blue during the Civil War. These fragments proved Filipinos had lived and labored in America long before annexation, but their traces remained scattered, easily overlooked.

Morro Bay, California (Source: Wikipedia)

It was into this faint prehistory that Ramon Reyes Lala stepped, offering something unprecedented: a name, a face, and a book.

Lala was born in Manila in 1857, when the Philippines lay firmly under Spanish rule. The city was a crossroads of empire: friars dominated schools, Chinese traders crowded the parian, and British and American merchants dropped anchor in the bay. Lala’s father trained him in commerce, teaching him to reckon accounts and measure goods, while his mother placed books in his hands—catechisms in Spanish, histories written from the conqueror’s perspective, and English readers brought by foreign merchants. Words and numbers quickly revealed themselves as tools of power, and young Lala longed for a stage larger than Manila’s narrow streets.

As a young man he traveled to England, and there he absorbed the polish that would define him. He studied in libraries, listened to debates in Oxford and London, and practiced his English until it flowed smoothly. He wore tailored suits, learned to carry himself with cosmopolitan confidence, and refined the manner of a man at ease among Europeans. Yet this polish carried ambiguities. In Manila he would return too English for comfort—suspect to Spanish officials, distant to some Filipinos.

By 1887, restless once again, he sailed for the United States. New York roared with immigrant voices—Irish, Italians, Germans, Jews, Chinese—all struggling to make their way. Into this mix stepped Lala, brown-skinned, impeccably dressed, his English honed by London, his Spanish and Tagalog intact. He declared himself a cosmopolitan Filipino prepared to interpret his people to Americans who knew almost nothing about them. In essays for periodicals he sketched Manila nights alive with fiestas, processions mixing Catholic ritual with local color, and even hints of Aguinaldo’s defiance. His sentences, written in flawless English, gave American readers both the exotic and the reassuring.

Then came a remarkable achievement. In 1896, despite court rulings that barred Asians from citizenship, Lala secured naturalization as a U.S. citizen. How he did so remain uncertain—perhaps through a loophole, persistence, or the benevolence of a sympathetic judge. But the certificate was real, and he carried it like armor. At a time when Chinese immigrants were excluded and Japanese denied naturalization; he could lift the paper and declare himself American. For an aspiring author, lecturer, and cultural interpreter, the document conferred rare authority.

Two years later, his timing proved providential. In May 1898 Admiral Dewey’s guns destroyed Spain’s fleet in Manila Bay. Overnight Americans hungered for information about the islands they had seized. Missionaries packed trunks, teachers speculated about classrooms overseas, politicians debated annexation, and families puzzled over newspaper maps. Into this void stepped Lala with a book.

The Philippine Islands appeared late in 1898, bound in green cloth stamped with gold. Heavy and handsome, it was designed for parlor tables and libraries, not newsstands. The frontispiece showed Lala himself—hair neat, suit pressed, eyes steady. The image told Americans that a Filipino could look like them, speak their language, and embody respectability. He dedicated the volume to Admiral Dewey and President McKinley, aligning himself with the conquerors. Inside, his prose traced Magellan’s voyage, centuries of friar rule, and the endurance of the people. He described volcanoes and rivers, rice terraces carved into mountains, abaca stripped for rope, sugar boiled to crystals, tobacco rolled into cigars. His tone was measured and explanatory, never strident, always instructive.

The Philippine Islands

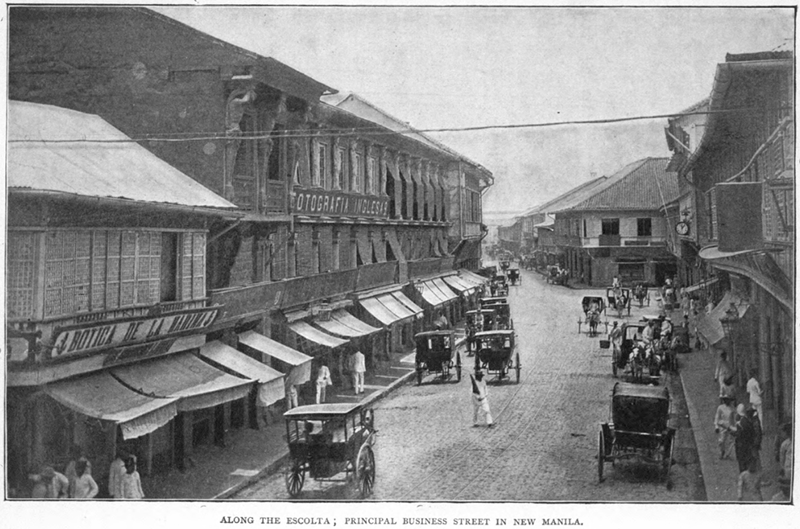

The illustrations gave the book its strongest claim. One plate showed two women in butterfly-sleeved gowns, faces direct and dignified. Another displayed terraces glittering with water, proof of ancient engineering. A Manila street scene bustled with vendors and carts, church towers looming in the distance. These images challenged stereotypes of primitivism. For many Americans, they were the first glimpses of Filipinos.

“Native Women” (Source: “The Philippine Islands” by Ramon Reyes Lala)

Reviews spread quickly. The New York Times praised the volume as a clear introduction to America’s new wards. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle emphasized its timeliness. The Los Angeles Herald repeated the claim that Lala was the only Filipino in America. The Chicago Tribune listed his lectures, while Protestant journals such as The Outlook and The Independent published his essays. Missionaries preparing to sail, teachers in small-town schools, and politicians in Washington alike turned to the book for guidance.

The contradictions were obvious. Lala condemned Spanish cruelty yet blessed American rule. He offered dignity in his images yet framed them as evidence of readiness for tutelage, not sovereignty. Americans embraced him precisely because his words reassured them. At a moment when annexation was controversial, he provided a Filipino voice that seemed to welcome empire.

Success in print carried him onto the lecture platform. The closing years of the nineteenth century were the golden age of oratory. Towns raised halls and Chautauqua tents, eager to host preachers, reformers, and travelers. Lala fit the circuit perfectly: fluent English, cosmopolitan bearing, rare citizenship, and a book to sell. Notices appeared in small-town papers: “A Native Filipino Will Speak.” Audiences arrived in starched collars and bonnets, expecting curiosity and instruction.

In Norfolk he described rice terraces like stairways to heaven, fiestas alive with color, and a people industrious and faithful. In Portsmouth he repeated the message: Filipinos were not savages but Christians, not hostile but receptive. In Boston, he faced sharper questions from anti-imperialists. He acknowledged Aguinaldo’s bravery but counseled patience, arguing that America’s schools and democracy would prepare the Philippines for eventual self-rule. Calm, measured, never combative, he reassured some and disappointed others.

Escolta (Source: “The Philippine Islands” by Ramon Reyes Lala)

On the West Coast his presence unsettled assumptions. Californians knew Asian laborers largely as farmhands or laundrymen. Yet here stood a Filipino in a tailored suit, fluent in English, lecturing on commerce and resources. In San Francisco he spoke of hemp, sugar, timber, and rice, promising profits and partnerships across the Pacific. Some nodded with approval, others sensed exploitation beneath the words, but all recognized the novelty.

Chautauqua tents in Pennsylvania offered another stage. Families picnicked outside, then crowded under canvas at dusk. Introduced as a man from America’s newest colony, Lala described his people’s music, faith, and diligence. The applause thundered, a wave of reassurance that empire was not conquest but benevolence.

Reporters praised his composure as much as his message. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle called him a revelation. The Los Angeles Herald repeated that he was the only Filipino author in America. The Outlook and Independent carried his essays further. To many Americans, he became not just an author but the Filipino voice.

Yet, contradictions shadowed him. In some towns he emphasized independence of spirit; in others, willingness to accept instruction. He praised Aguinaldo in print but distanced himself in lectures. He described Filipinos as intelligent but framed their intelligence as readiness for guidance. His flexibility kept audiences comfortable, but it also meant his words mirrored what listeners wanted more than what Filipinos demanded.

The lecture circuit was grueling. Train rides were long, halls alternately drafty or stifling, audiences insatiable. Yet Lala pressed on, knowing each appearance extended his reach, sold books, and strengthened his role. For a few years he seemed indispensable—quoted by missionaries, cited by teachers, and invoked by politicians. His presence gave Americans confidence that empire could be benevolent.

But novelty fades quickly in America. By 1905, the glow had dimmed. Reports from the Philippines told of guerrilla resistance, massacres, and the water cure. Headlines spoke less of benevolence than of brutality. Against such news, Lala’s message that Filipinos welcomed annexation rang hollow. Invitations slowed, audiences grew smaller, and newspapers shifted attention elsewhere.

He adapted by writing shorter pieces for magazines, turning from politics to culture. He described fiestas with nostalgic detail, sketched religious processions, and evoked the sounds of music drifting through Manila nights. These essays preserved the picturesque while avoiding the political. Readers welcomed the glimpses, but they no longer carried urgency. Meanwhile, other voices filled the field—missionaries writing memoirs, soldiers recalling campaigns, teachers reporting from Philippine classrooms. Compared to them, Lala seemed dated, a figure from the opening chapter of empire rather than its ongoing story.

Ramon Reyes Lala

His finances remained modest. Lectures paid fees, book sales brought income, but never enough for comfort. He lived in rented rooms in New York, his dignity intact but his circumstances fragile. Friends remembered him as courteous, careful in dress, reserved in manner. The man once introduced as “the only Filipino in America” had become one among many immigrants eking out a living.

As American rule deepened, the Philippines itself changed. English spread through schools, railroads and telegraphs bound provinces, and Filipino leaders pressed for autonomy. The Jones Act of 1916 promised eventual independence, though in distant terms. Newspapers in Manila carried debates unknown to most Americans. Lala, still in New York, watched from afar. Distance was his strength—it let him speak freely to Americans—but also his weakness, cutting him off from the ground he claimed to represent.

By 1915, America’s portrayal of Filipinos had shifted sharply. At the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, the Philippine exhibit displayed reconstructed villages of tribal groups, turning living people into anthropological specimens. Reformers spoke of progress, anthropologists of classification, politicians of benevolence. Against this spectacle, Lala’s images of dignified women and carved terraces seemed restrained, almost forgotten. Where he had once humanized his people, the fair reduced them to curiosities.

In his last years, his appearances were rare. Notices of lectures appeared occasionally in small papers, but without fanfare. He published fewer essays, and those that appeared carried little impact. When death came in 1921, the obituaries were brief. Some called him an author, others a lecturer, a few noted his rare citizenship. None recalled the halls he had once filled or the influence his book had wielded in 1898. His passing slipped quietly into the back pages.

Yet his book remained. The Philippine Islands still sat on library shelves and family tables, its gilt letters faded but intact, its illustrations still confronting viewers with dignity. Scholars later stumbled upon copies in secondhand stores, paused at the frontispiece, and wondered about the man whose eyes looked steadily back.

The contradictions of his life mirror the contradictions of empire. He gave Americans what they wanted: calm explanations, Christian respectability, promises of tutelage. He also offered glimpses of Filipino pride: women in formal dress staring back at the camera, terraces carved by generations of farmers, fiestas bursting with music. He lived the tension of being both interpreter and advocate, both Filipino and American citizen. For a time, he succeeded. When empire no longer needed him, he faded.

History, however, works differently than headlines. Scholars recovered his work, puzzled over his rare naturalization, and traced his lectures through scattered notices. They recognized that he stood at a crossroads—America searching for justification of empire, Filipinos struggling for recognition of humanity. He gave the first, withheld the second. That compromise does not make him villain or hero but human, caught in forces larger than himself.

For Filipino Americans who later built communities in Hawaii, California, and the Midwest, Lala was a distant ancestor of representation. Carlos Bulosan, writing in the 1940s, spoke of hunger, racism, and solidarity. Student activists in the 1960s spoke of labor, identity, and liberation. Community historians later chronicled struggles and achievements across the diaspora. Each filled the space differently, but the door Lala opened remained. His compromises illustrated the cost of early representation: to be seen, he had to blur himself; to be remembered, he had to be useful. When utility ended, memory faded.

And yet his legacy endures. The Philippine Islands was the first English-language book by a Filipino published in America. Its photographs still resist caricature, its prose still insists that Filipinos are a people of history and culture. Its dedication to Dewey and McKinley ties it to empire, but its survival ties it to memory. The book reminds us that empire does not erase entirely; sometimes it preserves fragments that later generations can reclaim.

A 2015 reprint of Ramon Reyes Lala's book from Jefferson Publication.

To place Lala in the long arc of Filipino presence in America is to see continuity and change. The anonymous sailor at Morro Bay left blood in the surf. Fishermen at St. Malo built shrimping villages on stilts. Manila men signed whaling logs in New England. Felix Balderry and Agustín Feliciano carried Filipino names into Union service. All left traces, but faint ones. Lala gave those traces a name, a face, and a voice Americans could recognize. He was not the first Filipino in America, but he was the first to be widely heard.

Consider his obituary once more: “Ramon Reyes Lala, author of The Philippine Islands, dead at 64.” Just a line, yet it anchored him to authorship. For a people so often erased, to be remembered as an author was no small achievement.

His contradictions were America’s contradictions, his rise and fall the rhythm of empire itself

His story closes with lessons larger than himself. It shows how empire shapes voices, lifting them when convenient, discarding them when not. It reveals how early representation often requires compromise, how dignity can coexist with subordination, how one man’s voice can stand in for millions, however imperfectly. It teaches that history survives not only in victories and monuments but also in books with fading gilt, tucked on shelves, waiting to be rediscovered.

From the Pacific surf of 1587 to the lecture halls of 1899, from parlor tables to secondhand bookstores, Lala’s journey bridged worlds. His contradictions were America’s contradictions, his rise and fall the rhythm of empire itself. His death in obscurity does not erase his moment in the light. His book remains, heavy in hand, its plates still showing women with steady eyes and terraces carved into stone. To study him is to glimpse America at the dawn of empire and to hear, beneath smooth sentences, the cost of being heard. That legacy, compromised yet enduring, is ours to remember.

Alex S. Fabros, Jr. is a retired Philippine American Military History professor.

More articles from Alex Fabros, Jr.