Palawan Museum Exalts ‘Boat People’ Refuge

/The Philippine First Asylum Camp Museum in palawan

Panicking, hundreds of thousands left the countries by whatever means, by foot or by boat

Overwhelmed by the influx, camps were established in most SE Asia countries – Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, Hong Kong (then still a British colony), and the Philippines to house those who fled. Of the Vietnamese alone, it is estimated that up to a million left South Vietnam, and about 200.000 perished along the way.

More than 50,000 made their way by boat to the Philippines, where the Philippine First Asylum Camp (PFAC) in Puerto Princesa, Palawan was set up in 1979, after temporary camps in different places had been established. Not too long after, the Philippine Refugee Processing Center (PRPC) in Bataan was established. Both were built with the support of the national government, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and international donors.

‘Fresh Off the Boat’

PFAC was for people “fresh off the boat” so to speak - asylum seekers, most of whom would stay for at least six months to several years while their status as refugees was established, or in some cases, rejected. Arrivals into PRPC, on the other hand, were from other camps in the South East Asian region, or from the “Orderly Departure Program” in Ho Chi Minh City, already assured of acceptance to third countries.

At PRPC they would stay for four to six months while their papers were processed, health screening done, and were enrolled in English and Cultural orientation sessions. Close to 500,000 people passed through PRPC during its almost two decades of operations. Many eventually were accepted in the US, Australia, Canada, and the European countries. In 1995, the US and Vietnam re-established diplomatic relations, the usual channels for migration were gradually re-established, outflows of people virtually ceased.

ENTRANCE TO World War II Memorial museum

‘Vietville’

Both PFAC and PRPC closed for good in 1996. A village, “Vietville” was built on the outskirts of Puerto Princesa, for some 2,500 remaining boat people who for various reasons were not accepted by third countries, or refused repatriation back to Vietnam. The village was built with the political support of the Catholic church and financed through fundraising among already resettled Vietnamese boat people. Most Vietville residents eventually left the Philippines, after years of being in a kind of “limbo,” as permanent residents, but not full Filipino citizens. Vietville exists to this day, though only a handful of residents remain, and a fine Vietnamese restaurant is still there.

Thousands of Vietnamese who once spent part of their lives in the PFAC remember their stay with fondness. The Palawan camp was unique—an open camp, with less restrictions; Vietnamese could go to the public market and the nearby beach. They could learn French or English, vocational skills like typewriting, sewing, automotive mechanics and computers; join various camp organizations, attend religious services. Many volunteered as interpreters, paramedics, utility workers, assisting camp administrators and the NGOs operating in the camp.

Inside the museum

‘World’s Best Refugee Camp’

Jan Top Christensen, Head of UNHCR Field Office from 1987-90, reminisces: “During my term, the numbers increased from 2.500 to more than 10.000. The camp had to be extended twice. In spite of the basic housing conditions and simple food, many Vietnamese today cherish their memories from their time in the camp. In many ways, life was like in a small Vietnamese town. Due to the Philippine authorities’ relaxed attitude, making it an open camp, and allowing establishment of small private businesses, the Vietnamese could leave the camp and many visitors enjoyed the good food in the camp. UNHCR designated the camp as the best refugee camp in the world at that time.”

PFAC Exhibit

PFAC Museum Excerpt- “Life in the camp”

Food was distributed daily from the food centre, run by the Vietnamese. Fresh food was bought in the local market. Rice and other dry staple food was sent by the World Food Programme. Firewood and charcoal were used for cooking.

Education was provided in Vietnamese to the young kids by CADP (Center for Assistance to Displaced Persons) and in English by teachers from a local college, the Holy Trinity College (HTC). Adults had several options: English and French classes, but also skills training like type-writing, sewing and automotive classes were offered. Even computer classes were offered in PFAC from 1989. Local and international organisations like ARMDEV, CADP, British Volunteers, Ecole Sans Frontieres, BRACE, and others helped out with education and other social services.

Health services were run by the International Organization of Migration (IOM) and the Red Cross. CMHS (CFSI) provided mental health support and counselling. Rotary Club ran the dentist clinic with dentist volunteers coming from all over the world and helping out for a period, in the camp. Other organisations like Japanese volunteers (JVA), and the Jesuit Refugee Services (JRS) also provided health services.

Each year, many former camp residents from all over the world return to Palawan, bringing their families and children to meet old friends and former PFAC staff. Some conduct charity and gift giving missions for poor residents of the barangays surrounding the former camp. When natural disasters hit the Philippines, groups of former PFAC residents raised funds for disaster relief, remembering how they were once welcomed into Palawan.

Thousands of Vietnamese who once spent part of their lives in the PFAC remember their stay with fondness.

Combat helmets from different nations (Photo by Vicente Salas)

Long Filipino Tradition

The Philippines has a long tradition of receiving refugees, from the Japanese Christians exiled in the early 17th century, led by the samurai Takayama Ukon (beatified in 2017), to Jews fleeing Nazism, “white Russians”, Chinese nationalists, and most recently, Rohingya from Myanmar. A UNHCR Post details nine “waves” of refugees who sought safer havens and were accommodated by the Philippines, even as other countries closed their doors, pushing people away. This is a tribute to the Filipino traits of empathy and willingness to help others. https://www.unhcr.org/ph/news/stories/nine-waves-refugees-philippines.

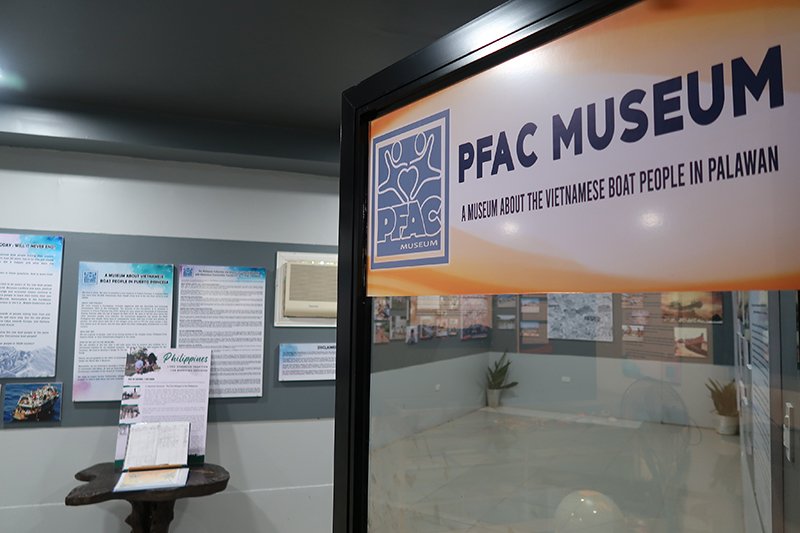

Meanwhile, during the COVID years, a group of former PFAC workers started meeting online, with plans to establish a small museum in Puerto Princesa, starting with a “virtual museum”. This has now evolved into the PFAC Museum, which opened formally in February 2025. It is an intensely personal endeavor–spearheaded by former PFAC OIC, ret. Admiral Mike Rodriguez and Jan Top Christensen; Rodriguez headed the WESCOM (Western Command), office in the camp in the ‘90s, responsible for camp organization, administration, security; Christensen became Danish ambassador to the Philippines in 2014.

Others involved include Rohima Sarra (former PFAC accountant, now a Judge), Benny Ong, (teacher), Jose Belleza (UNHCR staff), Thi Sen Kagahastian (former PFAC Vietnamese restaurant manager), the author, and Atty. Rod Libunao. All have been touched in a major way by the camp.

Palawan Special Battalion WW2 Museum

The PFAC museum display occupies a section of the WW2 museum; located along Rizal Avenue, in Bgy. Bancao-Bancao, less than a kilometer away from the site of where PFAC was once located. In 2011, the Mendoza family established the Palawan Special Battalion WW2 Museum.

Featuring World War II memorabilia items from the personal collection of Higinio “Buddy” Clark Mendoza Jr., son of Palawan war veteran and former Governor Higinio Mendoza Sr., who was beheaded by the Japanese. Puerto Princesa’s main public plaza is named after Mendoza Sr. The collection consists of vehicles, photos, weapons, literature, war-era currency, uniforms, and primary source records of the Palaweño guerrilla forces during World War II, also known as the “Special Battalion.” Over the years, the collection has grown as war veterans themselves, family, friends, and relatives--from other countries--continue to donate personal items–helmets, uniforms, flags, battle equipment.

Jeeps in the World War II Memorial Museum

The PFAC museum display outlines the history of PFAC and the experiences of the boat people, from frenzied, covert departures, dangerous sea crossings in flimsy fishing boats, arrival and stay in PFAC and the challenges with resettlement in a third country. It has vivid descriptions and photos of life in the camp. A snapshot of life in the camp and the many agencies who once worked there is in the box below.

A UNCHR post details nine “waves” of refugees who sought safer havens and were accommodated by the Philippines.

Today, virtually nothing of the former PFAC remains. The nipa-and-bamboo housing has long gone, together with the churches, Buddhist and Cao Dai temples; offices, classrooms, wells and fences; these were leveled when the international airport was built and the runway extended over two decades ago.

Nowadays, only the older generation can recall that there was once a PFAC. However, the presence of the Vietnamese in Palawan over the decades has left a lasting imprint on local culture, evident in the food–baguettes, banh mi, pho; and largely Filipinized “chao long” places ubiquitous and unique to Puerto Princesa.

Photos courtesy of Claudette Ensomo-Sendaydiego, Atty. Rohima Sarra, the Mendoza WW2 Special Battalion Museum and the author.

Dr. Vicente S. Salas was the chief medical officer and medical coordinator for the International Organization for Migration (IOM) at the PFAC, from January 1988 to June of 1989. He is a member of the Board of Directors of the PFAC Museum.