Our Stories, Ourselves

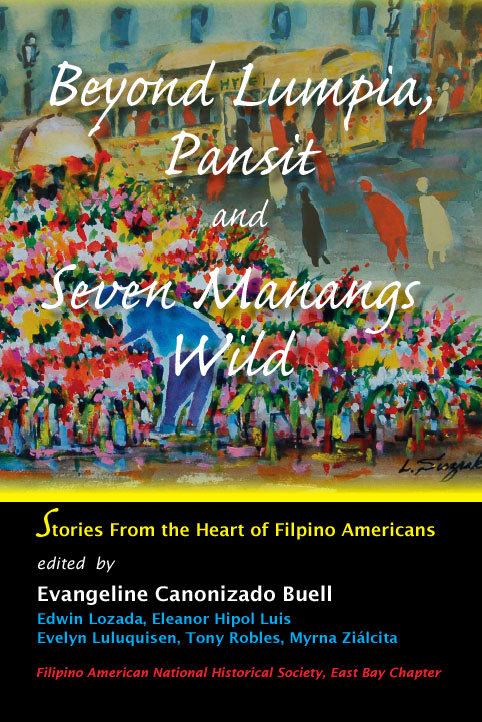

/Beyond Lumpia, Pansit and Seven Manangs Wild (Source: asiabookcenter.com)

Beyond Lumpia, Pansit and Seven Manangs Wild

Edited by Evangeline Canonizado Buell, Edwin Lozada, Eleanor Hipol Luis, Evelyn Luluquisen, Tony Robles, Myrna Zialcita

(Eastwind Books of Berkeley, 2014)

I was astounded by how deeply their gift symbolized the fruits of their hard work, their high regard for education—my education—something that had not been so easy to complete for them.

Lisa Suguitan Melnick’s story “Agtawid (Inheritance)” is one of the 49 literary works featured in Beyond Lumpia, Pansit and Seven Manangs Wild. As the title suggests, the anthology moves farther away from food as a cultural construct and offers vignettes and poems that resonate with our struggles and sense of connectedness.

Culled from the experiences and memories of the children and grandchildren of the manongs and succeeding waves of Filipino immigrants, the narratives are multilayered and bookended with themes of assimilation and discrimination: an occupational therapist anxiously waits for her green card; a young girl travels across the South with her Caucasian father and Filipino mother during the Civil Rights era; an educator refuses to settle for tolerance; a poet seeks out centuries-old Filipino roots in New Orleans; a granddaughter revisits her grandfather's migrant farm; a teenager engages his Filipino-American identity; a Filipino-African-American professor and author buoyantly straddles multiple cultures; a native San Franciscan retired Army major candidly talks about his formative years; a neglected carabao (water buffalo) finally finds home; a woman raised by her gay father in 1960s Berkeley writes about love, laughter, and how the right to marry should extend to all; a musician falls in love against the backdrop of Filipino-Latin soul; in lyrical tones, a young mother portrays seedtime and harvest; disturbing narratives of racism in schools, coming of age stories and stories of children caring for aging parents.

Editors of "Beyond Lumpia, Pansit and Seven Manangs Wild" (Standing L-R): Edwin Lozada, Eleanor Hipol Luis, Evelyn Luluquisen, Tony Robles. (Seated) Myrna Ziálcita, Evangeline Canonizado Buell (Source: asianbookcenter.com)

Also notable are:

Herb Jamero’s account of a postwar rooster fight. This primary source document flashes back to a time fraught with political and cultural conflicts; it places the blood sport in a sociohistorical context, acknowledging, “it was illegal as well as bloody and brutal, but also a significant social and cultural event within the Filipino culture.”

Jeanette Gandionco Lazam’s piece “Aunties Win a Tram Ride at Hanauma Bay” (in contrast to what must be presumably this anthology’s General American tone) is written in Hawaiian Pidgin, a likely nod to the Filipino community’s ties to the old Hawaiian plantations:

We just ‘bout to get on won tram we won notice da tram all full and da last two seats left, won haoles already took ‘em, so no mo’ room fo’ us.

Lazam’s other piece, “Walls and a Place Called Manila Town” is another primary source document recounting the author’s memories as a tenant at the old International Hotel: “The hallway outside my room, room 203 is dark; someone forgot to change the light bulb. I don’t care because I know how many footsteps it takes to reach the staircase, the toilet, and the end of the hallway where all our dreams have gone to die.” The I-Hotel, home to Filipino “old timers,” was demolished in 1981 and rebuilt in 2005.

“The narratives are multilayered and bookended with themes of assimilation and discrimination.”

Tony Robles, in his poem, “Up and Down,” paints a touching portrait of exile and survival:

Gerarda speaks to me in

English but then

she'll suddenly break

into Pilipino and she

thinks I understand

I sit and shake my

head and her voice sounds

like rainwater on the softness

of rocks which I understand...

Veronica Montes’ “Beauty Queens” is delightful and refreshing, and almost subtle in its reproof of the objectification of women:

“Hi girls,” he says. He salutes with one hand, while clutching his paper cup in the other. I’d bet a thousand dollars he didn’t get that cup of coffee himself. Auntie Cely brought it to him, or maybe one of our mothers. They always hover around him, making sure he’s comfortable, happy.

Girlie and I raise our eyebrows and cross our arms over our chests, but Mark stays put. Mark is unfazed.

“The Social Box” by Jean Vengua, in part also about Filipino queens, is framed within the context of sociocultural and sub-cultural identity:

How do you explain something like that? “Well, it's sort of like taxi-dancing.” But then you’d have to explain taxi-dancing—and it wasn’t that. I think the social box marked the end of something, too—although I’m still not sure what that is...maybe a different way of being a Filipina within Filipino communities in the United States.

According to The Atlantic, “six in 10 say America has grown more divided in the last decade.” Echoing this sentiment, Oscar Peñaranda, in “The Two USAS,” confronts the issue of polarization in American politics, economy and society and issues a challenge: “There is the USA who says E Pluribus Unum and the USA who does E Pluribus Unum... Do you belong to the ones who want to dismantle the schism or do you belong to the ones who don't care and by not caring and doing, keep the USA divided?”

Summing up the significance of this anthology, the editors iterate: “Through our writing, we combat amnesia and what destiny would otherwise hold for us, the casting of our personal stories and histories to oblivion.” Along these lines, I quote one of my favorite TV characters: “We're all stories, in the end,” with the best ones retold, passed down, and celebrated, so that even in the diaspora, the family remains indomitable and the community, mighty.

Aileen Ibardaloza-Cassinetto is the Associate Editor of Our Own Voice Literary Ezine (www.oovrag.com) and author of the poetry collection, Traje de Boda, published by Meritage Press in 2010. Her works have appeared or are forthcoming in Galatea Resurrects, Moria Poetry, Fellowship, Manorborn, and the anthology, Hanggang sa Muli (Tahanan Books, 2011). She is based in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Also from Aileen Ibardaloza-Cassinetto:

Lolo Claudio In Colorado: After The Poetry

July 14, 2014

The path a poet has taken is paved with her ancestor’s unrequited love.