Ordeal By Fire

/A US machine gun nest on a Manila street. The ruins across the street were typical of the rubble where our family hid on the night when our house was burned.

I remember a time when all this came together in the most traumatic experience of my life. This was the day when the house we were living in was bombarded by mortars of the U.S. 37th Infantry Division to clear a path for their advance into the Singalong District of Manila. This was in the month-long Battle for Manila that began on February 4, 1945.

During the Japanese occupation of Manila we lived in a house that was “loaned” to us by my brother John’s professor at the University of the Philippines. The professor learned that all our assets, even our home, had been confiscated by the Japanese secret police, the dreaded Kempeitai, when Japanese troops occupied Manila at the start of 1942. My dad was considered an “enemy of the Japanese Emperor,” and all our businesses and properties were seized. Dad himself was hauled away with other prominent Filipino and Chinese businessmen, politicians and newspaper publishers to New Bilibid Prison in Muntinglupa. Dad was imprisoned for three years until he was finally released because he was so sickly.

The UP professor had learned about our homelessness and unselfishly offered a house for us. When my brother pointed out that we wouldn’t be able to pay any rent because the family’s business was seized, the professor replied, “That’s OK, just pay me when the Americans come back.”

That was how we came to live in a house in the Singalong District. It was a serendipitous move because the suburb was one of the first to be liberated by the Americans after they crossed the Pasig River in the Battle for Manila.

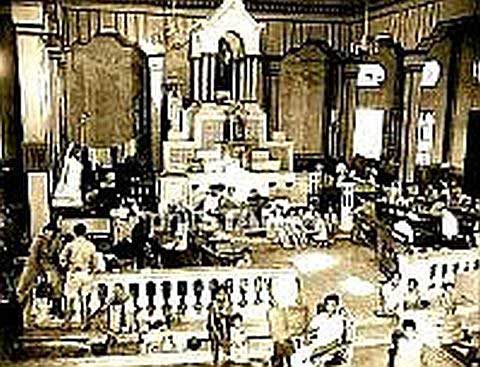

Singalong Church where we were liberated by elements of US 37th Division on Feb. 12, 1945. This photo was taken 2 weeks later, as the church filled up with people whose homes had been destroyed.

We could now hear the approach of the U.S. forces by the direction of the shelling and the fires that lighted the horizon. Our family debated where we should run to escape the shelling -- through the front lines toward the Americans, or to St. Scholastica’s College, which had been offered to us by the kindly German nuns who believed their building was safe because of their nationality. None of us could foresee the massacres of civilians of any nationality that would take place as residents tried to shelter in various concrete buildings thought to be “safe." During their liberation, Manila's residents were subjected to massacres by Japanese troops or shelling by "friendly" artillery fire. Sometimes both, as civilians tried to hide in concrete buildings like the Masonic Temple and De La Salle College on Taft Avenue, the Philippine Red Cross on General Luna, or the Luneta Hotel on San Luis Street. Both alternatives were equally deadly.

Curiously, on the night before our entire street was devastated and burned by shelling, Mother had a dream. In the dream, she heard the voice of her long deceased mother. The voice told her, "Do not go to St. Scholastica's."

A few days after the northern sector of Manila was liberated, on February 8th, the Americans began crossing the Pasig to fight in the south. Soon the whole Singalong District was under bombardment. When a barrage of shells hit our street, our house exploded in a fireball. Our neighbors, the Fernandeses, the Maios, the Thrashers all ran towards St. Scholastica’s College, but our family dashed out of our air raid shelter and ran in the opposite direction -- towards Singalong Church and the front lines. We had to hurl ourselves on the ground every few seconds to dodge the shells. It seemed as if we were the enemy! (We never saw or heard from our neighbors again after the war.)

When we reached the church courtyard, a shell landed among us and we heard Dad screaming. Dad was hit! We groped our way in the smoke and dust to him. His right arm was almost torn off, a piece of shrapnel had gouged large wounds on his shoulder and the right side of his body. He kept moaning, “Leave me here! Save yourselves, run for your lives!”

We brought him into the relative safety of the church, forced to step on a pile of about 25 or 30 dead Filipino civilians that had been dragged outside the entrance. Apparently these people had been massacred by enemy troops before we arrived. Then a Filipino man appeared, carrying a folded canvas cot. "Here," he said, "You can have this." We unfolded the cot and placed Dad on it. The cot was clean. We presumed the man was the sacristan and he had given us his own bed, but we didn’t see him again. We carried Dad beneath the altar. There was space for all of us to hide in.

When Dad was hit, many of us abandoned our knapsacks to help him. All of the knapsacks contained water and cooked food, among other things. I was very thirsty but there was no water available. As I peered out from the altar I could hear someone in the pile of dead bodies moaning and begging for water. The man was dying. Suddenly I saw my sister, Nora, come out. She knelt to give the man some water. I thought, "What a waste!" A few minutes later I looked at the man again. He was dead.

We all sensed it was not safe to spend the night in the deserted church. We had to leave before dark. So, while we could still see our way through the rubble, we left and spent the night hiding in the ruins of destroyed houses along Dart Street. During the night my brother saw enemy troops retreating along San Andres Street. The next morning he reported this to Mother, and she decided we would go back to the church.

Carrying Dad in the cot, we found a way back to the church. The shelling had stopped as we waited for the Americans to advance to our part of the district. My brother, John, decided to look for help. He met the advancing GIs and was told to speak to a combat medic who was walking with the soldiers. The medic told him he could not leave his troops, but he opened one of his bags and gave John a small pack. He told John how to clean Dad’s wounds and apply a pure white powder. This was sulfanilamide, he was told; it would delay the onset of gangrene. We had never heard of sulfanilamide before the war; it was a new drug to us.

(Left) A U.S. Army medical officer. These men are volunteers; they carry first aid and medical packs but no weapons as they advance in the front lines alongside regular troops.

(Right) The Weapons Carrier was a type of US Army truck, on one of which we hitched a ride to a hospital that was open in north Manila.

When John returned, we ripped off the strips of chemise dress that Mother had used to bind up Dad's wounds and John treated him. Then we placed a new pad from a box of Kotex that my sister had managed to save before fleeing our house. It was decided that the next morning four of us would carry Dad to the northern part of Manila, which had already been liberated. I would be one of the bearers. Although the battle lines were still unclear, Dad needed medical help as soon as possible.

Next morning the four of us set out, hoisting Dad on the cot. We walked through the ruins of Dart Street, went past the blackened Paco railroad station, which was the scene of very heavy fighting, and trekked through the Pandacan suburb until we reached the Pasig River at Nagtahan. We passed advancing U.S. soldiers. Enemy snipers infested the area, but we hoped they wouldn't fire on us, which would only reveal their position.

The Pasig River separates Manila into north and south. U.S. Army engineers had built a bridge made of floating pontoons alongside the blown up Nagtahan Bridge. We carefully walked across it, carrying Dad. Our combined weight made the pontoons sway back and forth but we made it safely. We had reached the liberated north of Manila.

The Nagtahan Bridge across the Pasig River was built of pontoons by U.S. Army engineers. While American troops crossed it to liberate the south sector, we and streams of civilians crossed it to freedom in north Manila.

John hailed a passing U.S. Army truck, a weapons carrier, and the American soldier driving it stopped for us. John explained our situation and pleaded for help to get to a hospital. The American said, “Get in!” He quickly drove us through Azcarraga Street and turned into Rizal Avenue to San Lazaro Hospital in the northern part of the city. As medical attendants carried Dad in, I waited in the lobby. I saw bloody pails and buckets on the floor. They were full of arms, feet and hands that had been amputated. Apparently no one had the time or place to dispose of them properly, which made me fear that Dad would lose his arm. As it turned out, his arm was saved; in fact his life was saved, thanks to the kindness of the U.S. Army medic who gave us a life-saving drug.

Kindness is one of the finest of human prerogatives. It gives meaning to suffering.

An act of kindness is an opportunity to share our humanity with others. The U.S. Army medic who gave a healing drug, the GI driver who stopped his truck for us, the Filipino sacristan who gave us his cot bed, and the UP professor who lent his house to us on credit, these were people who were there when most needed. They passed our way only once and we never saw them again. But those strangers and their random acts of kindness made all the difference.

Larry Ng was Radio TV Director for Grant Advertising International when he was invited to join ABS CBN Sales, after which he migrated to Australia just prior to the imposition of martial law. Following the downfall of Marcos, Geny Lopez Jr. asked him to return to ABS-CBN as Director for TV News and Current Affairs, a position he held for five years before retiring.

More articles from Larry Ng