On Tita Bootz’s Bucket List—Stop New HIV Infections

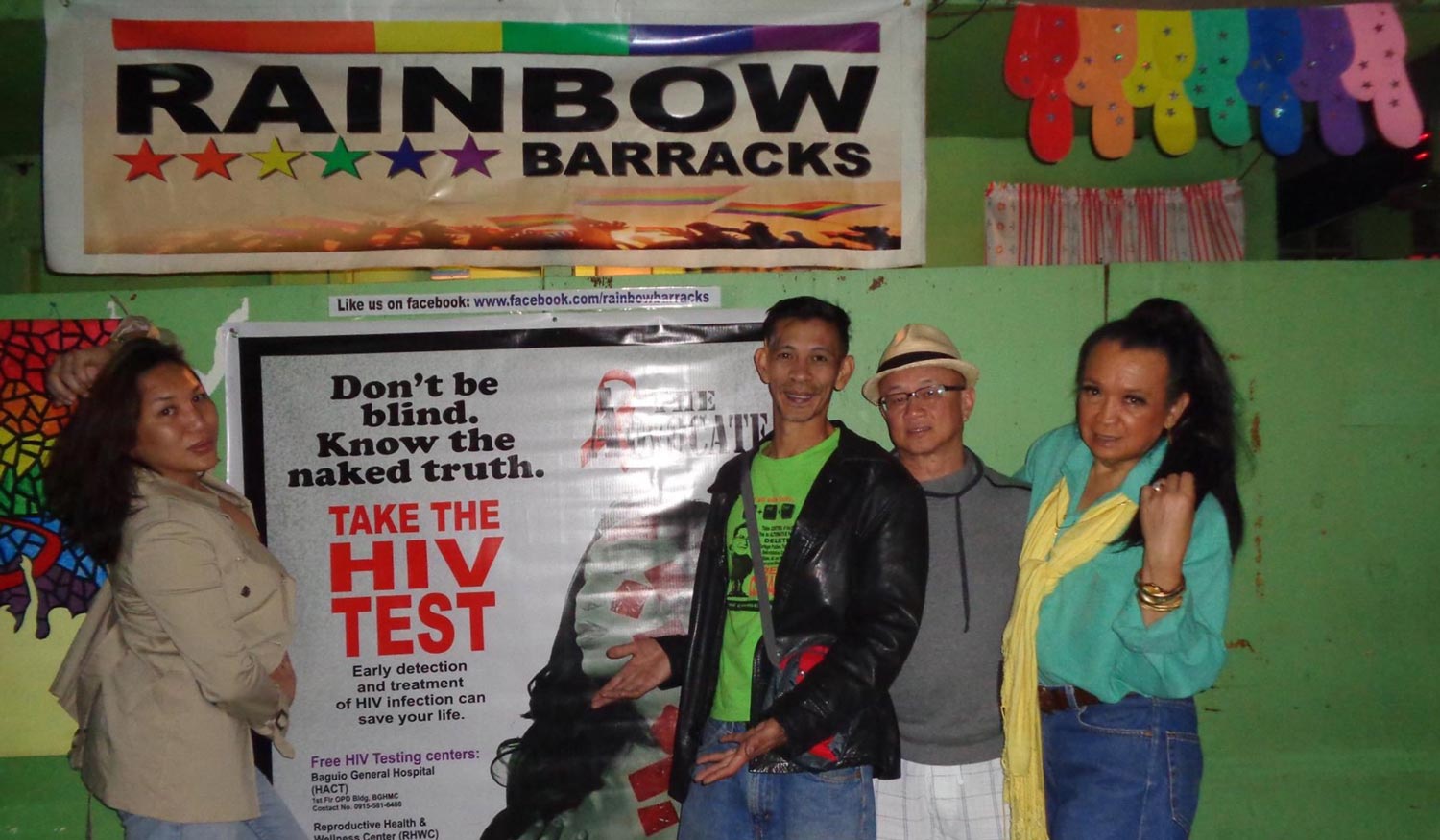

/Bootz Yabut at his Rainbow Barracks bar (Photo courtesy of Bootz Yabut)

But there is also bad news: In the Philippines, the numbers are going in the opposite direction.

A study by the Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network released at the last International AIDS Conference in Durban, South Africa, revealed that 74 countries, the Philippines included, saw increases in new HIV infection rates between 2005-2015. Apart from the Philippines, other countries included in the report were Egypt, Pakistan, Kenya, Cambodia, Mexico, and Russia.

Last year, 9,264 new cases were recorded by the Philippines' Department of Health. The number includes 1,113 AIDS cases and 439 deaths.

Overall, the Philippines has seen a total of 39,622 HIV cases, including 3,665 AIDS cases and 1,969 deaths. Health authorities now estimate that there are 30, possibly more new HIV infections per day in the Philippines, up from 1 case per day in 2008.

New infections are largely concentrated among key populations with specific risk behaviors, such as unprotected male-to-male sex, transactional sex and intravenous drug use. Sadly, only five percent of HIV-positive pregnant women have received antiretroviral medicines to prevent mother-to-child transmission.

Very few of those at-risk have taken an HIV test, with the number at zero for those under 18 years. (Lawmakers have proposed that minors be allowed to be tested for HIV without parental consent.)

Bootz Yabut -- Tita Bootz to friends and colleagues -- wants to change that.

Now 67 years old, Yabut, who identifies as gay, has a degree in medical technology and has worked in Kansas and the United Arab Emirates. Now permanently back in the Philippines, based in Baguio City, he has found a new calling: being a community HIV/AIDS advocate. And he does it all on a voluntary basis.

Volunteer Santy, Pastor Myke, author, and Yabut (Photo courtesy of Bootz Yabut)

Along with other community members, among them Pastor Myke Sotero of the Metropolitan Community Church, Yabut spearheaded the creation of a CBS -- Community-Based HIV Screening -- one of a few such groups in the country.

There is one difference with Yabut's group: It does not receive any government or private funding, except for HIV test kits (Rapid Immunochromatographic HIV Test Kits) provided by the AIDS Research Group of the Manila-based Research Institute for Tropical Medicine (RITM).

"I have to buy our disposable gloves, cotton balls and adhesive bandages," he said, adding that when asked to conduct HIV testing in nearby towns and cities, he pays for all the travel expenses.

Most of the HIV testing happens in the Rainbow Barracks, an LGBT community-friendly bar he owns in Baguio. But his group has gone to events in La Union and Pangasinan and other provinces, conducting HIV testing among jail populations.

“Seventy-four countries, the Philippines included, saw increases in new HIV infection rates between 2005-2015.”

Despite having no funding, the CBS Baguio has an impressive record of HIV tests conducted. Since it was first set up in February 2016, it has tested almost 2,000 individuals, close to 3 percent of whom tested positive.

Those whose tests come back positive are referred to medical facilities like the Baguio General Hospital, which in turn arranges for a confirmatory Western Blot test done by the STD-AIDS Cooperative Central Laboratory at the San Lazaro Hospital in Manila.

Unlike the rapid HIV test the group conducts, in which results become available within minutes, the confirmatory test can take weeks. Yabut's group tries to be in contact with the HIV-positive clients to check on how they're doing while waiting for their confirmatory tests results.

While the community-based HIV screening is not anonymous (names and contact information are requested), it is confidential -- only Yabut or his individual volunteers and the client would know the test result.

I asked Yabut what his motivation is for doing his HIV advocacy.

Yabut performing an HIV test on a client (Photo courtesy of Bootz Yabut)

"Now that I'm retired, I wanted to do something for the community -- especially the LGBTs and young people. There is no reason for the Philippines to buck the worldwide trend of declining new HIV infections. I want to see new HIV infections stopped before I die!" He seemed serious about his statement.

What makes the CBS successful?

Yabut says that his group treats clients like brothers, sisters and friends. In fact, he says that many of those they have recruited for testing often hang out in his bar -- including those who have tested positive. The bar holds events that promote better awareness about HIV and AIDS. "We even treat clients to a free drink when they come for testing," Yabut says.

Pastor Sotero told me that it works just as well that their group doesn't receive any funding because it shows to the clients that their advocacy is done purely out of concern for the community. Sotero has lost a loved one to AIDS.

On his 67th birthday in early May this year, many well-wishers came to Yabut's bar to greet him. There was karaoke singing, adobo rice, a flower bouquet and birthday cake for him.

It was a fun night for all, only momentarily interrupted every time Yabut goes into the HIV testing room to meet with a prospective client.

The CBS has a potential to be replicated in many more cities and towns in the Philippines. It can be an effective strategy to stop new HIV infections in the country, one HIV test at a time. Thanks to concerned individuals like Yabut, Pastor Sotero and their core group of dedicated volunteers.

Rene Astudillo is a writer, book author and blogger and has recently retired from more than two decades of nonprofit community work in the Bay Area. He spends his time between California and the Philippines.

More articles from Rene Astudillo