Nobel Winner Maria Ressa Sparks ‘Hope in Action’ at USF’s Yuchengco Philippine Studies 25th-Year Celebration

/Maria Ressa at the McLaren Conference Center in the University of San Francisco (Photo by Raymond Virata)

Guests, students, community leaders, and longtime friends of YPSP gathered from 9:30 a.m. to 1:30 p.m. on November 8, 2025, at USF’s McLaren Conference Center.

What began as a small academic program offering a Minor in Philippine Studies—made possible through a gift from the late Philippine diplomat Alfonso Yuchengco—has grown into a cultural home for Filipinos and Filipino Americans. It continues to inspire learning, dialogue, and the exploration of identity.

California’s 34th Attorney General, Rob Bonta, emphasized this impact in his videotaped welcome remarks: “Education is power. It empowers our youth to understand their roots, to challenge injustice, and to imagine a better future. That’s what [YPSP] has done for 25 years, and that’s something worth celebrating.”

California Attorney General ROb Bonta (Photo by Raymond Virata)

I had previously crossed paths with both Maria Ressa, the event’s keynote speaker, and Jose Antonio Vargas, the moderator for the subsequent one-on-one conversation.

My first encounter with Maria Ressa took place on April 29, 2014, during a Philippine Online Chronicles and Vibal Foundation media forum organized by my sister Noemi Dado’s group blog, Blogwatch.tv. For many participants, it was their first time seeing her onstage since she co-founded Rappler.com in 2012. Her talk focused on the future of media in the Philippines—digital journalism, the challenges of the evolving media landscape, and the promises of a networked world. In 2021, Ressa and Dmitry Muratov were jointly awarded the Nobel Peace Prize “for their efforts to safeguard freedom of expression, which is a precondition for democracy and lasting peace.”

I met Jose Antonio Vargas earlier, in May 2011 in Las Vegas, after a business summit convened by the National Federation of Filipino American Associations (NaFFAA). It felt like an off-the-books gathering of fewer than 25 Filipino American community advocates meeting a nervous but determined 29-year-old Pulitzer Prize winner. We were sworn to secrecy as “Pepetong” prepared to publicly “out” himself as an undocumented immigrant through his groundbreaking June 22, 2011 essay in The New York Times Magazine. His courage transformed national conversations on immigration, helping advance the DREAM Act and leading him to establish Define American.

Jose Antonio Vargas leads the Q&A session with Mari Ressa (Photo by Raymond Virata)

These two courageous trailblazers brought their shared mission to the YPSP celebration: to spark hope… in action.

Ressa’s Data, Stories, and Warnings

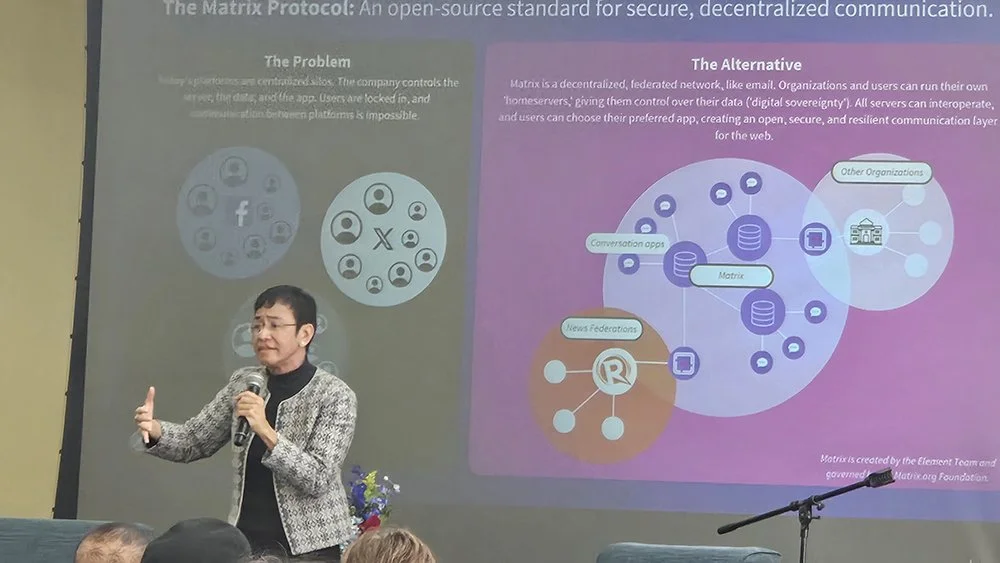

Maria Ressa explaining the “Collab”as a way to fight the disinformation wars (Photo by Raymond Virata)

True to her self-described “geeky” approach, Maria Ressa delivered a keynote interweaving data, research, and personal narrative. She anchored her message on three words: facts, truth, and trust. “Without facts, you can’t have truth. Without truth, you can’t have trust. Without these three, we have no shared reality.”

Ressa quickly grounded her talk in stark realities. “There are approximately 4.6 million Filipinos living in the United States,” she said. “We form the backbone of so many industries, from healthcare to hospitals, but we're caught between worlds—and increasingly between two information wars.” She noted that for six consecutive years, up to 2021, Filipinos in the Philippines spent more time online and on social media than any other population globally.

She cited Cambridge Analytica whistleblower Christopher Wylie’s characterization of the Philippines as “a petri dish” for disinformation: “Cambridge Analytica tested tactics of mass manipulation in our country. If it worked, they imported it over here. We were the guinea pigs, and America was the target.”

She added that the U.S. had the highest number of compromised accounts in the Cambridge Analytica scandal; the Philippines had the second highest.

Ressa continued: “Filipino Americans watched this information campaign in the Philippines lead to more than 27,000 deaths in the first three years of the Duterte administration. That’s according to human rights activists. But the true number? That’s the first casualty in our battle for facts. Until today, we don’t know exactly how many were killed.”

She described the killings of journalists, lawyers, and judges—examples of how democracy erodes when truth is weaponized. “Many of our families believed the lies that spread like lightning, enabled by the tech we carry in our pockets.” She emphasized that the same disinformation tactics later appeared in the United States.

Ressa’s roles at Columbia University—professor of professional practice at SIPA and inaugural Carnegie Distinguished Fellow at the Institute of Global Politics—also informed her preview of a major new report, The First 100 Days of Trump 2.0: Narrative Warfare and the Breakdown of Reality.

She peppered her keynote with anecdotes: her third-grade teacher’s mantra—“Maria, you always have to make the choice to learn”—and Hillary Clinton’s nickname for her, “Paula Revere,” for constantly warning others about disinformation (“The tech bros are coming!”). Ressa faced mounting danger in the Philippines.

She outlined the three distilled priorities from a collective of 300 Nobel laureates: (1) ending surveillance-for-profit; (2) eliminating coded bias; and (3) strengthening journalism as a defense against tyranny.

She then described the importance of an open-source, decentralized matrix protocol for media organizations—a new platform now called “Collab.” “Real people can have real conversations online,” she explained. “More than 150 groups work together every day, sharing fact checks that don’t spread as fast as the lie.” She noted that the Philippine Press Institute has joined the platform.

Inquiring Minds Want to Know

Ressa’s keynote was rich but accessible—no “nosebleed” despite the density of insights. Her conversation with Jose Antonio Vargas further deepened the discussion.

When Jose asked what it felt like to deliver the Nobel lecture, Ressa described it as “daunting,” partly due to the intense scrutiny and ongoing legal cases at the time. “I felt like I was representing journalists. I was representing Filipinos. Huge pressure!” Yet she also used the moment to express her belief in humanity’s fundamental goodness.

“Many of our families believed the lies that spread like lightning, enabled by the tech we carry in our pockets.”

Jose offered his own historical lens: the first U.S. census in 1790 counted 3.6 million people (including enslaved people counted as three-fifths). “There are more Filipinos in the country now than there were people in America in 1776,” he noted. “And there are more Filipinos in California than people in New Hampshire, Delaware, and Rhode Island combined.”

Another key topic was the “Great Replacement Theory,” which many attendees were unfamiliar with. Wikipedia describes it as a white-nationalist conspiracy theory alleging an intentional scheme to replace white populations in Western countries with non-white immigrants. Originating with French writer Renaud Camus, it has since spread into mainstream political rhetoric.

Ressa observed, “This wasn’t even on Fox News—it was so French. And now it’s running the government.” She noted that the U.S. today is 16% immigrant—“the highest it has ever been historically”—and argued that today’s immigrants (Indians, Mexicans, Filipinos, Chinese, Koreans, Haitians) parallel the Germans, Italians, Irish, and Polish of earlier centuries.

Throughout their dialogue, several themes emerged:

• Truth requires community. Journalists cannot defend facts alone—they need the public’s involvement.

• Identity is layered. Vargas encouraged young people to embrace, not flee from, their complex identities.

• Filipinos have agency. Both speakers insisted that Filipinos and Filipino Americans are not invisible—their choices shape society.

During the lunch break, I asked Maria Ressa: “What does Filipino community empowerment look like in 20 years?”

Her response was a challenge: “I can’t actually tell you that because code changes every two weeks. This is a moment of complete chaos and uncertainty, and how we get through the next year depends on how we act today. I’ll throw that back to you: What are Filipino Americans going to do?”

Lorna Lardizabal Dietz is a Filipino community publicist and cultural empowerment advocate. She serves on the board of directors of Sentro Filipino: The San Francisco Filipino Cultural Center.

More articles by Lorna Lardizabal Dietz