Mt. Pinatubo Disaster: When It Seemed Like the End of the World

/The blue truck fleeing the hot ash from Mount Pinatubo (Photo by Alberto Garcia)

JUNE 15, 1991

2:00 a.m.

USGS (U.S. Geological Survey) and PHIVOLCS (Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology) scientists at their command post inside Clark were roused from sleep by a staffer assigned to the infrared camera monitoring Mt. Pinatubo. He showed them what appeared to be a glowing trickle of pyroclastic flow on the slope facing Pampanga, about 1,000 feet long from the summit. It puzzled them because they knew there was supposed to be no river channel or gully where the pyroclastic rivulet was flowing. Suddenly a USGS scientist exclaimed, “It’s not a pyroclastic flow! It’s a crack on the side of the mountain!” It terrified them because a fissure on the side of an erupting volcano could cause a collapse of the entire mountainside and lead to a lateral eruption where the huge eruption column would blow horizontally instead of vertically. They agreed to hop into a helicopter at daybreak for an ocular.

Satellite photos of the Mount Pinatubo eruption (Source: USGS)

5:55 a.m.

Their planned ocular by helicopter never happened. After erupting on June 12, 13, and 14, Mount Pinatubo finally "exploded" early morning of June 15, 1991 (a Saturday). They knew it was the Big Bang because instead of a tall vertical column, the volcano produced a humongous cloud that was over 10 kilometers wide--the equivalent of an F-5 tornado--which engulfed the nearby mountains in the Zambales Range. Although it seemed like the crater had widened, it was actually just clouds of steam, gas, and debris bursting horizontally. The volcano was now ejecting a denser, heavier eruption column that was collapsing under its own weight, threatening to spill over around a wide area. It was the start of Pinatubo's Plinian eruption, named after the Roman scholar Pliny the Elder, who died when Mount Vesuvius erupted in A.D. 79. The scientists were really worried because their seismogram needles stopped swaying one by one, which meant that the seismometers installed on the volcano's slopes were being destroyed by spreading pyroclastic materials.

8:10 a.m.

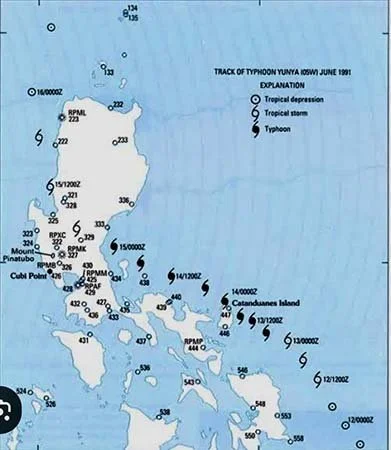

Typhoon Yunya (Diding) started its passage across the upper Pampanga River Basin area (Tarlac and Nueva Ecija). It was an incredible convergence of two forces of nature–typhoon and volcanic eruption–that had never happened before or since. At the moment of Pinatubo's climactic eruption at 1:42 p.m., the eye of the storm was 70 kilometers from the volcano's crater. Yunya's cyclonic winds (rotating counterclockwise) altered the atmospheric flow pattern and carried the ash meant for northern Zambales over to southern Zambales, and ash meant for southern Zambales over to Pampanga, creating a mess all over, like an industrial fan hitting a birthday cake and splattering its icing on the floor, ceiling, and walls. But at least it distributed the mess, instead of dumping it all on one side. Still, Subic got more than Clark did, and it's quite an irony, because that's where the 15,000 Clark servicemen and their families had fled and sought refuge.

The summit caldera at Mount Pinatubo (Source: Britannica)

10:27 a.m.

Mount Pinatubo was now erupting continuously. It was shooting up faster than the ash column could rise, so the column collapsed upon itself, raining tons and tons of ash and rock fragments all over Pampanga. It switched off the sun like a light bulb and plunged the province in total darkness. It was so dark you couldn't see your own hand stretched out in front of you, and the ash fall was so thick even sound waves couldn't pass through. Thus, everything was muffled, you had to strain your ear to hear conversation, like a movie with the volume turned low. The remaining soldiers at Clark saw the darkness creep across the parade ground, like an evil cloud or the angel of death shutting out every street lamp, porch light, car light, and flashlight that stood in the way. In Mabalacat, residents saw it as a solid black curtain being drawn down from the sky. They went out to the street mystified by the sight of pumice pebbles falling from the sky and pelting house roofs and car roofs, followed by a rain of mud, then sand. The rain doubled the weight of sand, and soon tree branches cracked, coconut trees folded like umbrellas, and house roofs started caving in.

11:17 a.m.

With the seismometers destroyed, and the typhoon’s low clouds obscuring Pinatubo, and the radar observatories malfunctioning due to wet ash fall, the scientists had become blind just as the show began, relying solely on fluctuations in atmospheric pressure as reflected on the barographs. Soon these barographs became redundant because the pressure from the eruptions was so intense the scientists actually felt the pulses pounding their ears.

1:42 p.m.

This was the exact moment of Pinatubo's climactic eruption, when the ash column reached an unbelievable height of 35 km. The explosion engulfed the eye of Typhoon Yunya, which was just 70 kilometers away from Pinatubo's crater. (You can say that the volcano ate a typhoon for lunch, because Yunya started disintegrating after this.) Volcanologist Julio “July” Sabit, who was in Zambales, called his boss, Dr. Reynaldo Punongbayan, who was in Manila. "Good evening, sir," Sabit began. Punongbayan replied, "July, it's only 2 p.m."

3:39 p.m.

The earthquakes struck after every two or three minutes, each measuring at least magnitude 4.5. Imagine being jolted repeatedly not just a few times, but hundreds of times, from 3:39 p.m. until 10:30 p.m.– that's seven hours of non-stop terror, enough to reduce even grown-up men to tears.

4:25 p.m.

The quakes intensified as the rising magma fractured underground rock layers. Each quake now registered magnitude 5.6 or above. The ground was now vibrating continuously, punctuated by larger quakes several times every minute.

The ash cloud of the Mount Pinatubo eruption from afar (Source: USGS)

6:30 p.m.

Two large quakes signaled the collapse of the volcano's summit wall. The PHIVOLCS spokesman said on radio, "We are now thinking of a worst-case scenario." PHIVOLCS expanded the original 30-km danger zone covering only Porac, Mabalacat, and Angeles to 40 km to include Magalang, San Fernando, Guagua, Sasmuan, and Olongapo, which meant that everyone in those towns must leave at once. An announcer screamed on radio, "Magsilikas na po kayong lahat (Everyone, please evacuate)!!" prompting thousands of terrified Kapampangans to jump into their vehicles and jam every road leading out of Pampanga, with hundreds of thousands more braving the rain, wind, and ash fall on foot–a scene straight out of The Ten Commandments. Some mothers were even handing their infants over to strangers in cars to save them from what they thought was certain death. There were wild rumors about the nuclear bombs at Clark detonating, or the whole province being swallowed up by a rapidly emptying magma chamber.

From Olongapo, Mayor Richard Gordon called PHIVOLCS chief Dr. Punongbayan to ask if he could evacuate his people (all 300,000 of them). The mayor’s plan was to commandeer a convoy of Victory Liner buses through Subic Naval Base towards the relative safety of the Bataan Peninsula. When Dr. Punongbayan hemmed and hawed (he first said, “Stay,” then called to say, “Go”), an irritated Mayor Gordon asked, “What’s the bottom line, Ray? Do we go or do we stay?” The PHIVOLCS chief finally said, “Stay.” They couldn’t have gone anyway, because there were only 30 buses to transport 300,000 residents, the roads were impassable, the muddy rain rendered the vehicles’ wipers useless, and the Subic base commander (an American) had turned down the mayor’s request for passage through the military facility. (Actually, because Subic and Clark were already under the SUBCOM and CABCOM, respectively, at the time, it was the Philippine Marines that were responsible for issuing passes to Subic, but the Filipino Marine general in charge of Subic was nowhere to be found.)

Quezon City Mayor Brigido “Jun” Simon drove to the expressway near Angeles City with a fleet of 85 buses and dump trucks to pick up evacuees, who complained that their own mayor, Antonio Abad Santos, had made himself scarce. The government-controlled Pantranco deployed its own buses to bring evacuees from Mabalacat to Quezon City, where they were taken to the Amoranto Stadium. The Jesus Miracle Crusade led by Wildy Almeda was holding its weekly prayer rally there at the time and refused to cut short the program to give way to the arrival of the evacuees, who had to wait outside until 5:30 p.m. Makati Mayor Jejomar Binay, chairman of the MMDA at the time, set up evacuation centers in Marikina, Pasig, Valenzuela, and Pasay.

Evacuees from Porac, Bacolor, and Candaba hiked all night towards Bulacan. By the time they reached Malolos, they were shivering and famished, and their hair and clothes were caked in cement-like compacted ash and sand. In Holy Angel University, the entire roof of its gymnasium collapsed, and so did the roof of the Rabbit Bus terminal in Angeles City, killing 30 evacuees. In Dau, three children and two adults died inside a barangay chapel when the roof caved in. At the Pampanga Agricultural College in Magalang, 1,500 US troops from Clark (the last to evacuate the military base) filled all classrooms and gym facilities, while thousands of Filipino refugees who had followed the soldiers to the college were not allowed inside the campus; so they spent the dreadful night on the streets and vacant areas outside the school entrance.

The aftermath of the eruption (Photo by Bruce Gordon, Science Photo Library)

In Balibago, a gas tank in the kitchen of Shanghai Restaurant exploded, setting the entire building on fire. A Japanese customer, who sustained second- and third-degree burns all over his body, had to walk all the way to Mabalacat in search of a hospital or clinic. (He ended up in my father’s clinic.). While all this was going on, the first lahars flowed through Sacobia, Abacan, and the other river channels, carrying boulders and logs from the mountains, which bulldozed every bridge that stood in the way. One by one the bridges fell in Angeles City—the upstream Friendship Bridge in Brgy. Anunas, the Abacan Bridge in Balibago, and the Pandan Bridge in Pulung Maragul. The lahars overtopped the Pampang Bridge in Hensonville and the bridge at the NLEx, where vehicles stuck in traffic were swept away. Levy Laus was there to witness it; the car in front of him plunged into the river, killing a doctor and his entire family. Many vehicles were also on bridges when they collapsed, drowning passengers in boiling mud. Bodies resurfaced downstream in Mexico town.

10:30 p.m.

The climactic eruption ended. The rubble from the collapsed summit had plugged the volcano’s vent four hours earlier, signaling the start of the waning period. Pinatubo’s peak had been reduced from 5,725 ft to 4,872 ft and on top of it was a huge gaping hole–the caldera, which would eventually fill with water and turn into the lake that we see today. Although the quakes continued the rest of the night, they started diminishing in magnitude and frequency.

It was an incredible convergence of two forces of nature–typhoon and volcanic eruption–that had never happened before or since.

5 a.m. the next day

And after the worst day and worst night of their lives, Kapampangans woke up dazed, confused, and exhausted, only to start the absolutely worst four years of their history, when lahars devastated their province, burying village after village, town after town, year after year, until something inside them snapped and released an inner force they never knew was there all along... and Kapampangans were never the same again.

From my book “Pinatubo: The Volcano in our Backyard”

4 Years Later

Diding and Mameng—two strange typhoons, four years apart, marked the beginning and the end of Pinatubo’s wrath, like two bookends framing volumes upon volumes of Kapampangan horror stories and endless tales of sorrow.

Diding (Yunya, photo 1) hit Central Luzon on the day of Pinatubo’s climactic eruption (June 15, 1991), its eye closest to the volcano’s crater at the precise moment of the eruption’s climax at 1:42 p.m. It was a cosmic convergence of two forces of nature (typhoon and volcanic eruption)—no such phenomenon has ever been recorded in the entire history of the world.

Diding

Lahars devastated Pampanga in the next four years, until the devastation reached its climax on October 1, 1995 when Mameng (Sybil, photo 2), an unusual storm that started in Mindanao, swerved north and devastated the Visayas, blew across Bicol Peninsula without losing energy, then made a direct hit at Metro-Manila and Pampanga—no typhoon had covered more area in the archipelago before or since. It rained for 14 hours over Mount Pinatubo, triggering lahar flows that pounded the last barangay standing in Bacolor—Cabalantian—and the next town that had until then remained safe: the capital city of San Fernando! Waves upon waves of lahars trapped Cabalantian's 13,000 residents on their roofs for 12 hours, some rooftops bearing as many as a hundred people standing shoulder to shoulder, hungry, dehydrated and shivering. We don’t know the exact number of people who perished that night, but after that, the lahars which stopped at the doorstep of the capital town, subsided and spared the remaining towns of Pampanga.

Robby Tantingco is the Director of the Center for Kapampangan Studies and Vice President for External Affairs of Holy Angel University. He is the author of "Destiny and Destination" and "Pinatubo: The Volcano in our Backyard" which won a National Book Award.

More articles by Robby Tantingco