Lives Larger Than Themselves

/That same year, students in New York and Berkeley, Paris, Prague, Tokyo, were in full revolutionary mode, instigating sit-ins, mass protests, marches, even violent tactics, against the powers that be for their complicity in supporting a colonial and outmoded global order, and for their refusal to be part of the solution rather than be the problem. The potheads and the flower children, even as they were tuning in, turning on, and dropping out (to use a favorite phrase of those hallucinogenic days) had the same sentiments as the activists: opposition to the Vietnam War. In Manila, as early as 1966, Kabataan Makabayan (Nationalist Youth), founded by José Maria Sison, and under the wing of the Soviet-leaning Partidong Komunista ng Pilipinas (PKP), had protested President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Philippine visit to participate in the Manila Summit, meant to formulate a regional response to the ongoing conflict in Vietnam.

In 1968 Sison broke with the PKP and went on to establish the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP), looking to Mao’s China instead. The next year he and Bernabe Buscayno, or Ka Dante, oversaw the formation of the New People’s Army, the military arm of the CPP, which continues to lead an armed insurgency that is one of the world’s longest running.

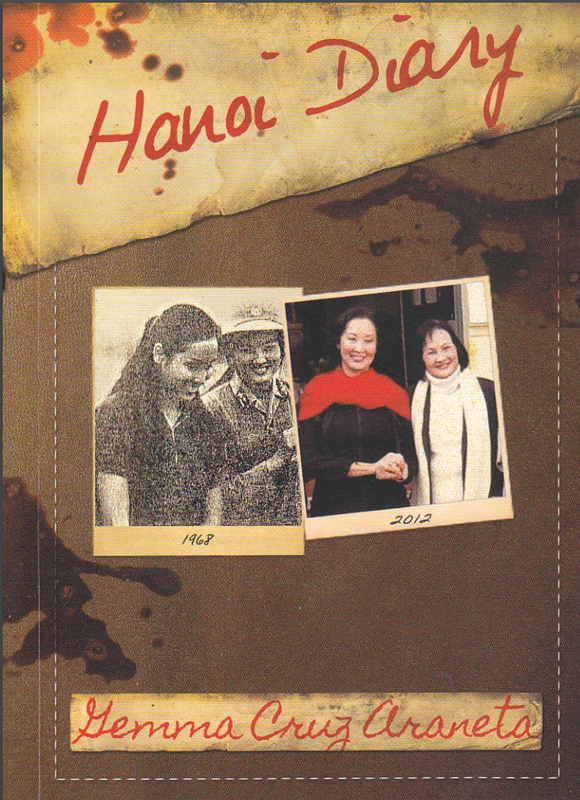

In May of that year, Gemma Cruz Araneta, who had in 1964 won the Miss International—the first Filipina to win such a title—went on a clandestine visit to North Vietnam with her husband, Antonio Araneta. Gemma was our very own Jane Fonda even before Jane Fonda’s trip in 1972. Gemma kept a diary of that trip, published as Hanoi Diary later that same year. I never knew of its existence until its republication in 2012, when her younger brother, Ismael “Toto” Cruz, a classmate and friend of mine since high school, gave me a copy. He had had it reprinted—the imprint is Cruz Publishing—44 years after it first came out. (Brother and sister, by the way, happen to be descendants of José Rizal.)

Gemma Cruz Araneta's "Hanoi Diary"

She and her husband stayed for about a month, with Gemma noting what they saw and their interactions with the North Vietnamese, from military and civilian officials to women in villages that had been affected by the U.S. bombing raids. Though the physical damage was enormous, the Northerners were not cowed. In her entry for May 25th, she writes: “Now that we are in the provinces, I am even more convinced that American bombings have not produced the results the Pentagon or Washington are hoping for. Instead of breaking the morale of the Vietnamese, bombings have consolidated and united them, aroused their patriotic spirit and inspired them to work as hard as they can. Bombings have also helped their government belie all the propaganda dished out by the U.S.A.”

It was Gemma’s first but her husband’s second visit. He had been to Hanoi in 1966, and was able to interview Ho Chi Minh—or Bac Ho (Uncle Ho) as his countrymen called him—which he wrote up for Graphic Weekly in December that same year. (The feature is included in the reprint of Hanoi Diary.) He and Minh discussed the Manila Summit, which the latter described as “a council of war.” Minh also referred to the non-combat contingent of Philippine soldiers sent by Marcos to South Vietnam as Araneta’s “unfriendly” compatriots. Araneta asked Ho Chi Minh if he had any message for the Filipino youth. He had: “Tell them that Ho Chi Minh wants them to become good patriots. And that one way to become good patriots is to become communists. If you are a communist you are a true nationalist and you do not risk the danger of degenerating into a fascist type of nationalist. If your heart is communist, you become an internationalist. You become a nationalist and an internationalist at the same time.”

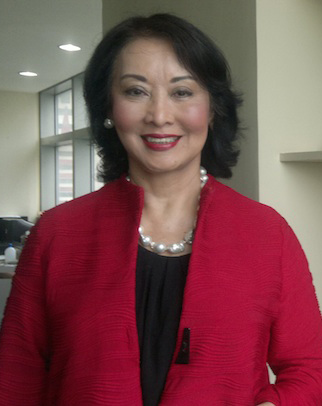

Gemma Cruz Araneta (Photo by Ricky Torre/Source: rappler.com)

The reprint includes not only the diary, of course, and the Araneta article, but also an account of the couple’s return visit in 2012, upon the invitation of the Vietnamese government. This time there was no need to fly there on the sly. Hanoi and Washington no longer view each other as an enemy. If anything, the dispute with the People’s Republic of China over who controls the South China/West Philippine Sea—likely the biggest sea grab in history—has driven the two former antagonists closer together, just as it has meant the reopening of Philippine territory to the U.S. military.

Nowadays, the former beauty queen writes a column for The Manila Bulletin, following in the footsteps of her mother, the well-known journalist and memoirist Carmen Guerrero Nakpil. The president of the Heritage Conservation Society, she also gives talks on history and her illustrious forebear, Rizal.

The same year that Gemma was making her first trip to Vietnam, my older sister Myrna, who was the same age as Gemma and who passed away in 2010, was already a member of the ICM Congregation—the Belgian order of nuns that founded and ran St. Theresa’s College, of which Myrna and my younger sister Judith were alumnae, and which I attended as a kindergartner.

My Ate Myrna was never the goody-goody type, never a santa-santita, and her decision to hie herself to a nunnery came as a surprise to all of us in the family and to her friends. It was completely unexpected, and revolutionary, not in the overtly political way but in the stricter sense of the turning over, in this case, of a life.

She had always led an active social life, had had suitors and a job in the corporate world, but one night, after a party, it came to her this way, as recounted in The Party’s Over: A Nun for Modern Times/ The Story of Myrna H. Francia, ICM: “In college, I was open to be discovered by Mr. Right, but instead the Hound of Heaven caught up with me. One night, after an enjoyable party and as I was taking off my hurting shoes and my make-up, a song kept ringing in my head. ‘The party’s over / It’s time to call it a day/ They’ve burst your pretty balloon and taken the moon away.’ I became pensive at one in the morning. ‘All is fleeting, only God’s love suffices. God is the thirsty one, and I the chipped cup, half empty and waiting to be filled.’ With these realizations, I sought to quench my thirst for perfect love.” I remember her telling me this, that it was Frank Sinatra she heard crooning that late night. I am absolutely sure the Hoboken singer would have been tickled pink to learn of his role in helping to shepherd my sister onto the path of spirituality rather than that of worldliness.

Myrna H. Francia's "A Nun For Modern Times"

Other than her brief autobiography, the book, edited by veteran editor and journalist Lorna Kalaw Tirol and assisted by my sister, Judy, consists of her poems and various other writings, and reminiscences by her three siblings (Joseph, Judy, and myself), friends, and colleagues. Many of Myrna’s poems were new to me. I was particularly struck by this one, with its nod to José Garcia Villa and Emily Dickinson:

Where, ever, will, I, go, to, grow,

Not, old, but, bold, of, spirit?

When, shall, I, feel, you, heart, to, heart?

Stop, this, journey, of, hurt, to, hurt,

Open, these, my, eyes, to, beauty.

“My Ate Myrna was never the goody-goody type, never a santa-santita, and her decision to hie herself to a nunnery came as a surprise to all of us in the family and to her friends.”

Myrna often referred to God as “She,” shocking her older co-sisters. She went on to spend close to half a century as a nun—this year, 2016, would have marked her golden jubilee—wearing various hats, from trainer of would-be missionaries in Belgium, where she learned to speak Flemish, to district superior of the order (for which she traveled throughout the Philippines), from student counselor to retreat director, from teacher to pastoral worker in urban poor areas. It was a vast vineyard that she labored in.

Part of that vineyard was the less than pastoral Bagong Barrio, a vast urban poor settlement in Caloocan, surrounded by factories that recruited from the abundance of labor available but almost always refusing to pay decent wages. She and a couple of co-sisters lived and worked there. I visited her once, on one of my balikbayan trips, staying for a few days. It was a grim, depressing, even toxic environment, and to this day I believe contributed to the cancer that finally led to her demise in 2010.

Joseph, Judy, and I, with some of her friends and colleagues decided to continue her work. Thus in 2011 was formed the Sister Myrna Francia Memorial, Inc. (SMFMI), to provide vocational training for deserving but financially pressed young men and women, so they can find employment and gradually move out of poverty. Having no endowment, SMFMI relies entirely on donations and continues to fund a number of scholars’ education. Some have gone on to regular employment.

Both Hanoi Diary and The Party’s Over are eloquent testaments to quite different lives, but lives nevertheless engaged positively with the world, fully cognizant of the moment but always aware of a larger, humanitarian/spiritual dimension. [An updated version of a August 2013 Inquirer column.]

Copyright L.H.Francia 2013/2016

Luis H. Francia is the author of "Eye of the Fish: A Personal Archipelago" and the poetry collections "Museum of Absences" and the soon-to-be-released "Tattered Boat". He writes an online column for the Philippine Daily Inquirer.

More from Luis H. Francia