Harvesting Grape in Coachella, Weekends in L.A.

/Journal of a ‘60s California Farm Worker, Part 3

These five essays are pieces of my life, each one capturing a chapter in my journey from a young migrant laborer to a United States Marine. They begin in the Imperial Valley, where I worked the lettuce fields alongside other Filipino farmworkers, learning the rhythms of planting, cutting, and packing under the desert sun. From there, the story moves to Gonzales, where the asparagus harvest tested both body and will, and where the camaraderie of the bunkhouse softened the hardships of the work.

In Coachella, the grape harvest unfolded alongside weekends in Los Angeles — a mix of backbreaking field labor and fleeting moments of youth, music, and romance. Delano follows, where I arrived in September 1965 during a turning point in farm labor history, as Filipino and Mexican workers stood together in strikes that would reshape the agricultural industry.

The final essay brings me into the United States Marine Corps, where the discipline, endurance, and teamwork I had learned in the fields became the foundation for my military service.

Together, these essays are not just my personal story, but also a record of a generation of Filipino Americans whose labor and lives were deeply woven into the history of California and the nation.

Francisco and Maria Tapec are Filipino grape pickers in Coachella. Although Filipino workers were a large and important part of the farm labor workforce in the Coachella Valley from the 1920s to the 1970s, very few grape workers come from the Philippines today. (Photo by David Bacon)

That pay phone was a lifeline. Whenever I had a dime, I’d call my parents in Salinas. My grandfather, who had worked the 1934 and 1936 lettuce strikes, gave me a small notebook with important numbers written in pencil. He also had a P.O. Box in Coachella, inside the town hall post office. Every few days, I’d take the pickup and drive into town to check the box. Sometimes I’d get a letter from home, sometimes, nothing. But checking that mail was a kind of ritual. It connected me to something beyond the fields.

Our day began before sunrise. We’d wake in the dark, wash in cold water, eat a fast breakfast—two fried eggs, pan de sal or toast, sometimes rice—and pile into the trucks by 5:00 a.m. Once in the fields, we worked until the afternoon heat burned the grapevines dry. We cut table grapes, filled lugs, and loaded them onto trucks that waited along the dusty rows. Freeman’s foremen walked up and down the aisles with clipboards, watching but never helping.

Each evening after dinner, we gathered near the bunkhouses. Some played poker, others told stories or shared cigarettes. And more often, we talked about the rumors. “They’re trying to freeze wages,” someone said. “They won’t negotiate,” another muttered. The older men had seen it before. The younger ones, like me, were eager to fight back.

It was around the first week of May when Peter Velasco came to visit. He was a Filipino union organizer from Stockton and a man with history. He had marched in the old days, before the war, and carried himself with the confidence of someone who had already seen too much. He arrived in the afternoon and waited for us to return from the fields. That night, after dinner, he stood up in the chow hall and introduced himself.

“Brothers,” he said, his voice calm but firm, “the growers are counting on you to stay quiet. Don’t give them that.” He told us about the union’s goals: fair wages, steady contracts, better housing, and an end to the favoritism and racial segregation that divided the camps.

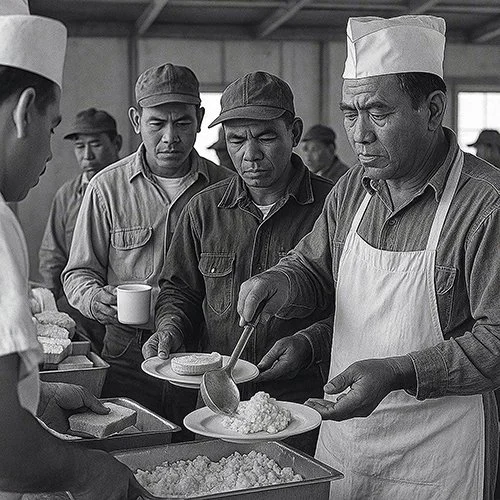

At the chow Hall (Image courtesy of Alex Fabros, Jr. This image has been digitally enhanced using AI.)

I remember one of our crew asking how much it would cost to join.

“A dollar,” Peter said. “Just one dollar. But one dollar from each of you can move mountains.”

I looked at my grandfather. He reached into his wallet and pulled out two crisp $20 bills. “Sign them all up,” he said. “And tell the union they better come back. We’ll be waiting.”

The next day, Peter returned. This time, he brought Chris Versoza Cruz, another organizer, who shared stories from Delano and Stockton. They spoke in Ilocano, Tagalog, and English. They knew how to move a room. The energy that night changed everything. We began holding regular meetings in the chow hall. Some of us made handmade signs—"Makibaka! Huwag Matakot (Fight, Don’t Be Afraid)!" and "Union Now!” — and stashed them under our bunks.

Tensions rose quickly. On May 10, the Los Angeles Times ran a small piece about resistance in Coachella: “Growers resist union push as Filipino crews begin talks of strike.” That same week, The Philippine Mail published a front-page article: “Filipino Laborers in the Coachella Valley Organize for Justice.” It was the first time I saw our fight in print.

Some of the growers weren’t pleased. One foreman told us, “You talk to those union boys again, you’ll be out.” Another docked our pay for a lunch break he claimed we took too long. But we didn’t stop.

In the Filipino Advocate, Manuel Buenviaje wrote, “The Filipino workers at Freeman Ranch are showing the spine of their manong ancestors. There is something brewing in the heat of Coachella.”

By mid-May, we started noticing unmarked pickups slowly circling our camp at night. Windows tinted. Engines low. No one ever stepped out. Sometimes, we saw headlights on the hillside watching us after dark. We knew we were being watched. The threat wasn’t just about our jobs anymore.

Then the violence began.

One night, as three of our younger crew walked back from the local grocery store near Thermal, a car swerved off the road and threw glass bottles at them. One was hit on the head. Another had to be stitched up at the county clinic. No police report was taken, even after we complained. “Probably just kids,” the officer said. We knew better.

Two nights later, rocks were thrown into Camp 2 from the back fence. Someone had a slingshot or a wrist rocket. One bunkhouse window shattered. One of our guys chased the suspect through the lemon orchard but lost him in the dark.

That was when the young Filipinos retaliated.

A night watch was formed. Five or six men, mostly younger, stayed up in shifts. They took to walking the perimeter with batons fashioned from scrap wood. Some carried farm tools tucked under their jackets. And when another group of white youths showed up to shout slurs at the gate, they got more than they bargained for.

The Desert Sun ran a small column titled “Tensions Flare at Freeman Labor Camp,” quoting a sheriff’s deputy: “These Filipinos aren’t afraid. They fight back.”

Still, we stayed. We harvested. We organized. We endured.

I never forgot what Coachella taught me: that even in the heat of the desert, among bunkhouses and broken promises, unity could bloom like the grapes we left behind.

I drove to Los Angeles as many weekends as I could. After long weeks of backbreaking work in the desert heat of Coachella, the promise of city lights, music, and the company of friends was too strong to ignore. Los Angeles was freedom. It was escape. It was where my cousin Maurice lived, my gateway to another world.

Maurice DeLeon had an apartment in Santa Monica, perched on Ocean Avenue with a clear view of the Pacific. He had style—tailored shirts, cufflinks, and a green Jaguar XKE in the driveway, which he later painted red. He had once been married to Beverly Aadland, Errol Flynn’s last girlfriend, and he moved through the city like a man who belonged. On one of my earliest trips that spring, Maurice greeted me at the door, tossed me a towel, and said, “Shower first, then Chinatown. Dim sum waits for no one.”

After a quick rinse, I joined Maurice and his date, Holly, at a dim sum parlor in L.A.’s Chinatown. Our waitress recognized him instantly. “Same table?” she asked. We dined on siu mai, char siu bao, and chicken feet while sipping jasmine tea. Maurice told jokes in Cantonese and made the room laugh. It was a world away from Camp 2.

That evening, we changed into suits, mine a borrowed gray one that didn’t quite fit, and drove up Sunset Boulevard in Maurice’s freshly painted red Jaguar. Holly wore a cocktail dress, and her lipstick matched the glow of the Strip. We arrived at the Playboy Club around 5:00 p.m., where Maurice was a lifetime member. At the door, he greeted the doorman by name, slipped him a $10 bill during a handshake, and we were escorted inside with no wait.

Dinner was formal: steak Diane, escargot, and Cognac. A Bunny snapped our photo with a Polaroid and handed it to Marian, the girl I had been paired with that night. She was a UCLA student, quiet but witty, and had a spark in her eyes that matched my own excitement.

After dinner, the Bunny Hostess led us into the lounge, where a live band played soul and jazz. We danced, first as couples, then closer. I could feel Marian’s hand tighten in mine during slow songs. She leaned in, whispered stories about her classes, her parents’ disapproval of the club, and how this was her escape too.

We got a table in the front, danced until past midnight. As we left the club, Maurice handed me the keys to his red Jaguar and said, “I’m going to take Holly home in a cab.” I turned to Marian and asked, “Where do you want to go?” She looked at me without hesitation and said, “With you.”

We spent the next hour dragging Sunset Boulevard, laughing, talking, radio low and windows down. Eventually, we returned to the apartment. We got acquainted. But I slept on the sofa.

She woke me the next morning with coffee and a smile. We sat on the balcony, looking at the ocean, our knees barely touching. “I’ll come to your boot camp graduation,” she said.

I nodded. “I’d like that.”

That day, she drove me back to Chinatown in her white Mercury Comet. We shared a dim sum lunch, and she handed me the Polaroid from the Playboy Club. I tucked it into my wallet.

When I returned to Coachella, the desert felt a little less lonely. I had one foot in the fields and one foot in the city. And for the rest of that summer, whenever I had a break, I drove back to Los Angeles, always in search of light, music, and Marian.

By the last week of August 1965, the grapes in Coachella had mostly been picked and packed. The harvest season was drawing to a close, but something bigger was beginning to stir in the wind. That summer, the conversations around Camp 2 had grown more serious. Names like Itliong, Vera Cruz, and Peter Velasco came up more often. Word was spreading of trouble brewing up north in Delano. The Mexicans were considering walking out. The Filipinos were already organizing.

Larry Itliong (second from left) and Cesar Chavez (second from right) leading the Delano grape strike workers (Source: UFW.org)

Peter Velasco returned to our camp last week of August. He didn’t come alone. This time, he was joined by Larry Itliong, a stocky, no-nonsense union man with deep ties to the Filipino labor movement. They didn’t need to convince us. Most of us had seen what happened in Salinas in '34 and '36. My grandfather had fought in those strikes and had lived to talk about them. He told us then, “If you don’t strike with your feet, you’ll strike with your stomach.”

I remember sitting in the chow hall that night, Velasco standing near the front with Itliong beside him. “We need you,” he said simply. “The growers in Delano won’t budge without a fight. We start on September 8.” Itliong followed, speaking partly in Ilocano and partly in English: “We go together or we fall apart.” That was enough.

The next day, I packed my duffel bag, grabbed the red Jaguar keys from Maurice—he had offered to let me take it up north—and shook hands with the crew. A caravan formed: a mix of 1953 to 1965 cars, three trucks filled with gear, and our crew of 40. Camp 2 slowly emptied as we drove north on Highway 99, the sun setting behind us.

The road to Delano wasn’t just asphalt. It was a ribbon of memory and struggle. As we drove, I thought of Marian. I thought of my grandfather. I thought of the men who cut lettuce before me, who faced clubs and bullets just for asking for a fair wage. Now it was our turn.

Delano was dry, dusty, and tense. We arrived in early September and settled into a labor camp just south of town. The Filipino Community Hall became our sanctuary. We met every night. Plans were drawn, picket lines assigned, speakers rallied the workers. The air was electric.

On September 8, the Filipinos struck. The Mexicans held back, at first. But within a week, the NFWA, led by Cesar Chavez, joined us. History was set in motion.

I never forgot what Coachella taught me: that even in the heat of the desert, among bunkhouses and broken promises, unity could bloom like the grapes we left behind.

Endnotes

[1] "Filipino Laborers in the Coachella Valley," The Philippine Mail, May 3, 1965.

[2] Peter G. Velasco, interview with the Filipino American Experience Research Project, 1993.

[3] "Coachella Growers Resist Union Push," Los Angeles Times, May 10, 1965.

[4] Manuel Buenviaje, "We Worked the Fields and Fought Back," Filipino Advocate, June 1965.

[5] Testimony of Alex S. Fabros, Jr., California Ethnic History Archives, Box 18, Folder 3.

[6] "Phone Booth in Camp 2 a Lifeline for Many," Desert Sun, May 17, 1965.

Bibliography

• Buenviaje, Manuel. Voices from the Grape Rows: Filipino Labor in Coachella. Los Angeles: Bayanihan Press, 1972.

• DeLeon, Maurice. Oral History Interview by Alex S. Fabros, Jr., 1987. Filipino American Experience Research Project.

• Fabros, Alex S., Jr. Field Notes and Letters from 1965. Private Collection.

• Velascp, Peter G. Oral History Interview, 1993. Filipino American Experience Research Project.

• Ilagan, Pedro. Letters from the Fields: Dispatches from Coachella. San Francisco: Katipunan Press, 1968.

• Ramos, Mari. "Church Supports Strikers with Sandwiches and Prayer." San Francisco Chronicle, June 3, 1965.

• Rivera, Daniel. “Picket Lines and Picket Fights.” La Opinión, May 29, 1965.

Suggested Reading

• Cruz, Vera. The Other Side of the Strike: Filipino Voices from Delano. Delano: Kalayaan Books, 1975.

• McWilliams, Carey. Factories in the Field: The Story of Migratory Farm Labor in California. Boston: Little, Brown, 1939.

• Pomeroy, Earl. The Pacific Slope: A History of California, Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Utah, and Nevada. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1965.

• Vallejo, Arnold. Brown and Manong: Race, Class, and Labor in the Coachella Valley. San Diego: Magsaysay Institute Press, 1981.

• Wong, Diane. Southern Exposure: Chinese and Filipino Encounters with the West Coast. San Francisco: Eastwind Books, 1982.

Alex S. Fabros, Jr. is a retired Philippine American Military History professor.

More articles from Alex Fabros, Jr.