Growing Up in UP’s Area 1, a Model Neighborhood

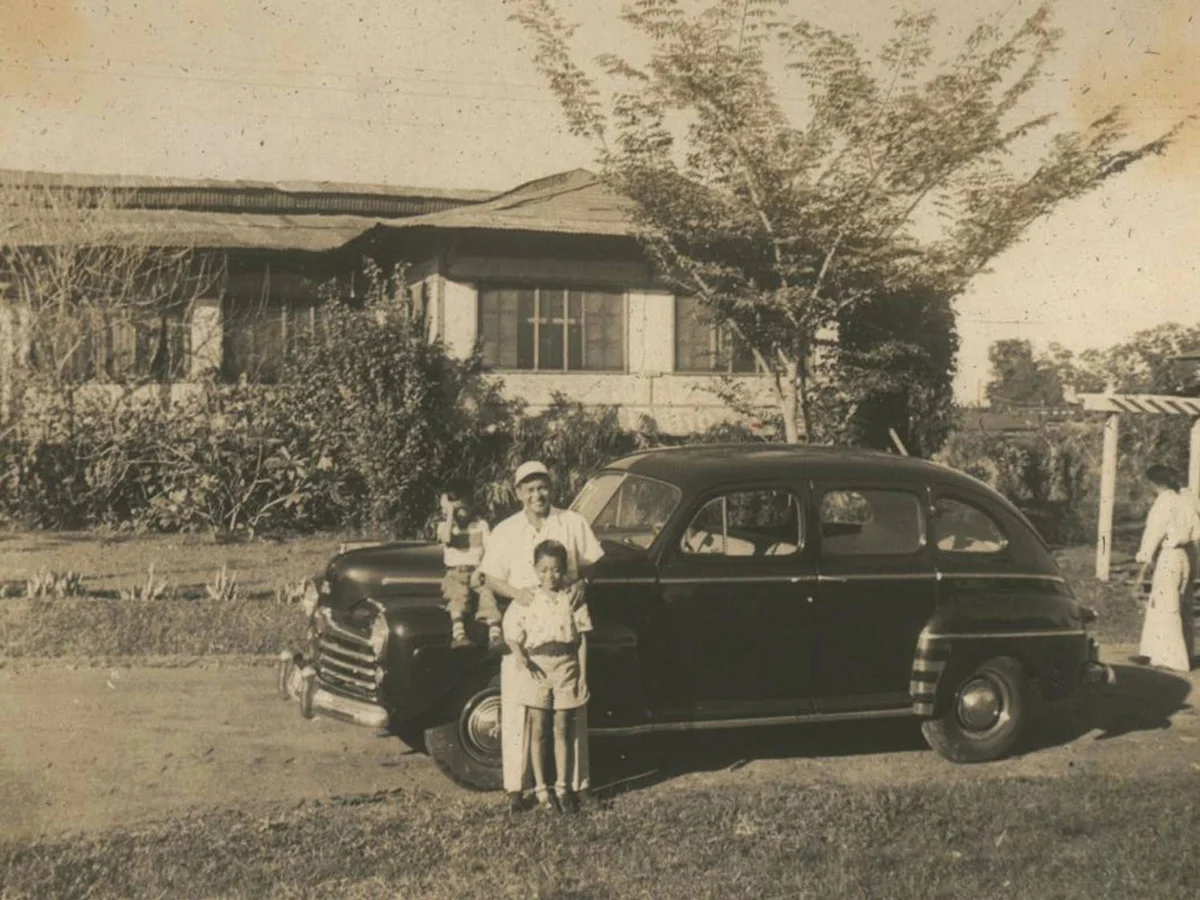

/The Einsiedel father and sons c. 1952 on Agoncillo St., Area 1. The house in the background was one of the WWII-vintage sawali houses occupied by UP faculty. It was later demolished to give way to concrete houses. (Photo courtesy of Nathaniel von Einsiedel)

UP assigned the lot to my mom who was then an instructor in the Physical Education Department, and my parents built the house. Ours was the third “permanent” house in Area 1, the first being the Ortigases’ and the second was the Cervanteses’. They were referred to as permanent because all the other houses that existed then were made of wood and sawali (bamboo slats) and were planned to be replaced. Those old sawali houses were left behind by the American soldiers who used to occupy the entire UP campus as their base.

The assignment of lots to faculty members to build their own houses was not only in Area 1. It was also done in Area 14 and 17. It was under UP’s program of encouraging its faculty members to live on campus. Actually, many faculty members and non-academic personnel were assigned to the old sawali houses that were spread all over the campus. Faculty members who were assigned empty lots to build their own houses on – like my parents – either could no longer be given a sawali house, or opted to build their own abode.

The homes built by faculty members themselves were called “pioneer” houses, referring to those who pioneered to live on campus. During that time, the nearest commercial center to the campus was Quiapo. The UP campus then was thought to be so far away! There were only a few buses that plied the Quiapo-UP Campus route, and their trips were spaced one hour from each other.

Area 1, the Neighborhood

One of the things I remember distinctly about Area 1 was that our family knew practically every other family in the neighborhood. Maybe it was because all of the adults were either UP faculty members or non-academic personnel, and all the children went to the same UP Elementary School. Maybe it was because there were not that many families living in the area, thus making it easier to know each other. Maybe it was because almost all of the adults just walked to work, while we children also just walked to school. Maybe it was because Area 1 then basically had only two streets – Agoncillo and Aglipay – and they formed a loop, thus allowing residents of one street to meet and socialize with residents of the other during afternoon strolls.

Another thing I remember about growing up in Area 1 is that we frequently had neighborhood parties. Our parents would often organize parties for the adults as well as for the kids whenever someone was celebrating a birthday. This practice of neighborhood parties went on through our growing up years – from the children’s birthday parties to the pre-teens’ dance parties to the collegiate soirees. These parties were also often potluck and outdoors. Everyone then had a large yard, so it was no problem holding outdoor parties.

There were no playgrounds in Area 1 then. We had to create our own sports fields in the open spaces that abounded in the neighborhood. For example, the area behind the Infirmary used to be a huge open space where we played our own version of “war games.” Every time UP’s maintenance people cut the cogon grass, we would build two small huts made of kakawate branches and the cut cogon. We would camp in these huts and sometimes even cook our own lunch, which was often rice and tilapia that we caught in the Cervanteses’ pond, or frogs that we caught from the rice fields behind Area 3.

The Cervantes children c. 1950s in front of their house, one of the pioneer houses in Area 1. (Photo courtesy of Bernie Cervantes)

One time we grouped into two teams, and each team tried to destroy the other team’s hut by firing flaming arrows from homemade bamboo bows. When one flaming arrow hit one of the huts, it quickly caught fire. Because the cogon was still fresh, it caused a lot of smoke. The next thing we knew, the UP firetruck was on the way with its siren blaring and people were running to see where the fire was. We all scampered home and watched from the safe distance of our houses as the firemen hosed the fire down.

In another open space that was centrally located in the neighborhood, there used to be a huge duhat tree. We used that tree as a sort of a “clubhouse” especially during the duhat fruiting season. We would often climb the tree to pick the duhat and lie on its branches to relax from the heat of the sun. Some kids were very good in climbing to the thinnest of branches just to reach the ripe and juicy duhat. Most of us had to be content with the not-so-ripe duhat in the thicker but safer branches. But not all of us were so lucky. Bobby Lesaca, for example, fell off the duhat tree twice and on both occasions fractured his bones. Curiously, at each occasion when Bobby fell, he was rushed to the Infirmary by the Infirmary’s new ambulance. We heard later that Bobby’s parents told the Infirmary not to buy another new ambulance, because this might cause Bobby to fall once again from the duhat tree!

A Model for Future Neighborhoods

Area 1 was, in our days, a real neighborhood. There was a strong sense of identity, security and community. Area 1 was a social living environment. It gave us experiences that have helped us to learn to better relate to other individuals. Nowadays, modern subdivisions do not recognize that the neighborhood is a meaningful social unit, often going unrecognized as an important element in the design of the urban environment.

Most subdivisions today are merely sites where houses are located with very little interaction between households, where each household owns a separate lot separated by a fence. As a result, modern urban society is lacking in the quality of human relationships, where people tend to find human contact in substitute and contrived activities. The lack of meaningful social relationships for many in today’s urban society is apparent in our lack of deep, lasting friendships and our preoccupation with superficial relationships based on status.

The importance of making neighborhoods conducive to a spirit of cooperation and mutual support, instead of isolationism and mutual distrust, cannot be overemphasized. Our state of mind, and even our physical health, are profoundly affected by the social climate of our neighborhood environments. There are elements that are essential to a community in order for it to function well over time. Some of these elements can be found in the Area 1 we grew up in, such as:

The Church of the Risen Lord (aka Protestant Chapel) and the Infirmary mark the entrance to Area 1.

Appropriate scale. Just as large or small cities have advantages and disadvantages, so do large or small neighborhoods. There is not much diversity if the neighborhood is very small, such as the old Area 1, but it is easier to know all the residents well. Larger neighborhoods offer diversity and can become stronger economically, but as they get bigger, they lose the feeling of community. The famous anthropologist, Kirkpatrick Sale, in his book Human Scale, presents a number of arguments that indicate that 500 people is an optimum number for a neighborhood community in order to have social harmony. He cites studies that show that it is when a population reaches 1,000 that a village begins to need policing. Evidently, in communities where people know one another, it is comparatively easy to keep the peace and to restore it once broken. The old Area 1 had fewer than 1,000 residents even during school days.

Boundaries. Clear boundaries make it possible for people to know where one neighborhood ends and the next one begins. They allow the neighborhood to be grasped and appreciated as a unit. Some neighborhoods establish boundaries with fences and streets. Area 1 even today has such boundaries, although it has become more “porous” – the old abode fence on the eastern and northern sides now have a number of pedestrian openings. In the 1950s and 1960s, we knew exactly where the boundaries of Area 1 were, even where these were not fences. On the southern side was the Ilang-Ilang Women’s Dorm and street of the two chapels and Infirmary; on the western side was an open space on the other side of which was Area 3 and Area 2; and on the northern and eastern sides was the adobe fence.

Security and safety. Many of our modern neighborhoods, including the present-day Area 1, are becoming increasingly prone to the depredation of burglars, vandals and so on. The usual response is to put up fences around individual homes and even the entire neighborhood and to hire security guards. One cause of crime is the failure of residents to control the surrounding open space, including streets, where intruders if unchallenged can commit criminal acts. In the old Area 1 where residents knew what places were public, semi-private and private, we easily recognized who were neighbors and who were outsiders. We often used the streets and open spaces as play areas and through this were able to keep an eye on the area. This helped us assert our dominance against unwelcome persons. Of course, it helped a lot that there was a strong sense of community in Area 1. Where neighbors know and care about one another, they will also act to protect the fellow residents from a suspicious stranger.

Privacy. Physical privacy is essential to an individual or family, as well as to the development of a sense of community. Where physical barriers do not provide enough privacy, social barriers develop as substitutes. The large lots in Area 1 (some having more than 1,000 square meters) provide significant physical privacy. So do the trees and vegetation. Individual houses are spaced far enough that the distance acts as a sound insulation. The surrounding plants also serve as physical screens such that windows do not look directly into other people’s houses. Without these features, the privacy of families would be compromised and, in its place, means of social withdrawal will develop – such as neighbors making it point not to get to know one another so that they can maintain distance or anonymity.

A lot of green space. The many benefits of green open space are well known: They make the microclimate cooler, thus reducing the need for air-conditioning; they clean the air of pollutants, thus maintaining a healthier environment; they contribute significantly to a much more pleasant and restful neighborhood, which is good for our mental health; and they help in developing more creative, environmentally friendly, intelligent and cooperative children.

Abundant open space and big trees have been one of the most visible and appreciated features of Area 1. We used to have a lot of fruit trees – mangoes, santol, kaimito, etc., which we harvested and shared with our neighbors as often as we could. The area’s vegetation is so lush that in the satellite image of the entire UP campus, no streets or houses in Area 1 can be seen as these are all covered by the trees.

“Area 1 was, in our days, a real neighborhood. There was a strong sense of identity, security and community. Area 1 was a social living environment.”

Conclusion

The neighborhood functions well when people feel that they are safe and can rely on help from others. It functions well when they can grow in their ability to get along and work out their differences. It functions well when, through participation in community activities, including work and fun in groups, they experience inner warmth and fullness which comes from feeling that they as individuals are part of the community, and that the community as a whole is part of all humanity.

Area 1 was once such a neighborhood. It accommodated most if not all the features of a well functioning neighborhood. It has now changed. But it has nurtured and produced some outstanding persons and, perhaps for this reason, it can serve as a model for future neighborhoods.

Mabuhay ang Area 1!

Dinky von Einsiedel was an Area 1 resident from 1952 to 1969, and an alumnus of UP Elementary School, UP High School, and UP College of Architecture. He is a registered Architect and Environmental Planner in the Philippines, and was formerly Regional Director for Asia-Pacific of the United Nations Urban Management Programme. He currently manages his own consulting firm, Consultants for Comprehensive Environmental Planning, Inc. (CONCEP).