Filipino Language and Its Discontents

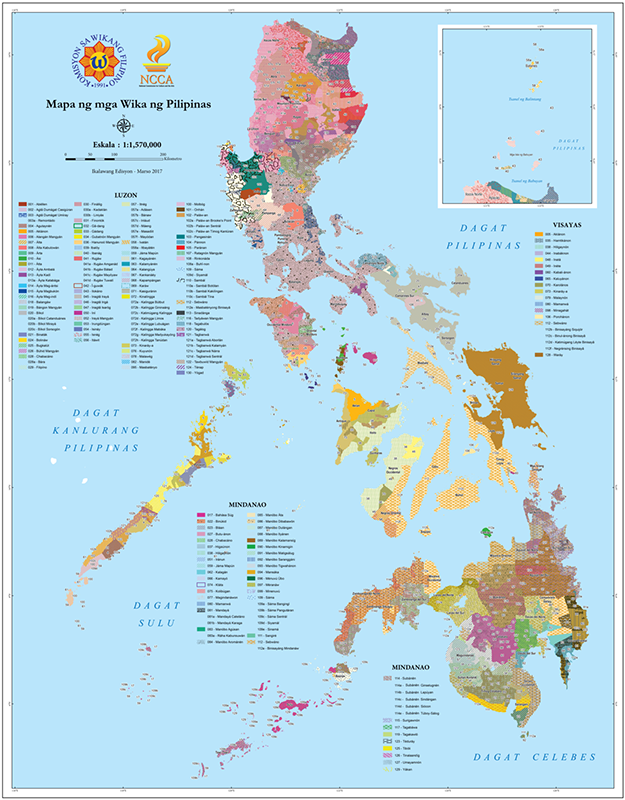

/The map of Philippine languages by the Komisyon ng Wikang Filipino

If you ask them to explain what a dialect is, they’ll say that it is anything that isn’t spoken nationally. That’s all wildly incorrect. For one, the actual linguistic definition of a dialect has nothing to do with political designations like “national” or “regional.”

A dialect is a variety of a language that is mutually intelligible with other dialects. Native Tagalog speakers cannot understand Cebuano, Ilocano, Kapampangan, and so forth. That alone proves that they are distinct languages.

However, many Filipinos would defend an incorrect definition of language and dialect as if their lives depended upon it. They are taught to take circular-logic nonsense to heart: “Non-Tagalog Philippine languages are dialects because they’re unimportant, and unimportant because they’re dialects.”

They have a faulty knowledge of history. Centuries of imperialism have also conditioned many Filipinos to be afraid of learning, as if intellectual curiosity would disrupt their sense of identity.

History Matters

But the truth is, by the time the Spanish Empire “discovered” the Philippines, the archipelago was already home to more than a hundred thriving societies and languages. The Spaniards were far from benevolent, brutalizing the natives and laying waste to their cultures, particularly the lowlanders.

The Spaniards did not hesitate from bloodshed in their colonial endeavour such as their 1663 slaughter of the babaylan (animist leader) Tapar and his followers in Oton, Iloilo. After the latter group staged a parody of the Catholic doctrine, the Spaniards shoved a bamboo pole through the sole woman member’s private part and fed the whole group to crocodiles.

The Spaniards’ crimes against the natives were grave and plentiful. However, and this is not meant to excuse their atrocities, some credit must be given to their scholarship regarding the Philippine languages.

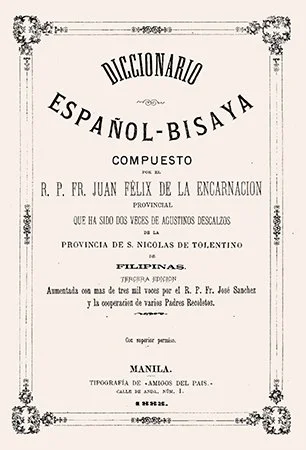

The Spaniards produced many valuable documents on the Philippine languages, such as Juan Félix de la Encarnación’s diccionario español-bisaya (Spanish-Visayan Dictionary) and Mark of Lisbon’s Vocabulario de la lengua bicol (Dictionary of the Bicol Language).

De la Encarnacion's Spanish-Cebuano dictionary

While flawed and undeniably influenced by racism, their research was still a lot more accurate and rigorous than the American colonizers’ propaganda literature. When American colonial rule began in the Philippines, things went from bad to worse. The idea that Philippine languages were merely “dialects” took hold in this era. The Spaniards learned the native tongues to achieve their imperialistic objectives, while the American colonizers kicked off the constant devaluing of Philippine languages that persists to this day.

Do You Speak Filipino?

The Philippine government did not begin developing the Tagalog-based “Filipino language” until 1937, yet another fact disproving the notion that Philippine languages like Tagalog, Cebuano, Ilocano, and so on are merely “dialects.” But 88 years after its creation, has “Filipino” remained the same as Tagalog? In 1996, the late linguist Ernesto Constantino argued that Filipino has more phonemes, different orthography, and more words borrowed from English than Tagalog. In short, Filipino is less “pure,” so it’s no longer the same as Tagalog.

Eleven years later, Ricardo Ma. Nolasco, then-chairman of the Komisyon ng Wikang Filipino (Commission of the Filipino Language), who had a PhD in Linguistics, disputed those arguments, pointing out that Filipino and Tagalog still share identical grammar and that they remain mutually intelligible. “Certain academicians equate Tagalog with ‘purist’ usage and Filipino with ‘non-purist’ usage. [...] But whether it is simple Tagalog or deep Tagalog, pure Tagalog or halu-halo (mixed) Tagalog, it is still Tagalog. They all belong to the same language,” he explained. In the same piece, he urged Filipinos to also cherish other Philippine languages besides Tagalog/Filipino.

Ricardo Ma. Nolasco (photo by Marianne Lorraine M. Samiling)

Nolasco wrote from a position of high importance, yet his words have gone unheeded. To this day, Filipinos continue to treat Tagalog proficiency as the benchmark for being a real Filipino. In a 2011 interview with Philstar, Fil-Am actor Darren Criss shared that his mother was from Cebu. Directly after, the Filipino interviewer Raymond Gutierrez said, “Give us some Tagalog words or phrases.” It wasn’t phrased as a question, but a command, despite Criss saying that his mother was from Cebu. “Well, my mom doesn’t speak so much Tagalog, actually. She speaks more [Cebuano],” Criss replied. Due to this, he was more familiar with Cebuano himself, not Tagalog.

A student who won a contest for a unique Cebuano literary form in 2023, yet another reminder of a cultural gem that we might lose if we continue to neglect our languages (photo by Mary Iazah Faye Alburo)

Filipino celebrities, whether they’re based in the Philippines or the diaspora, face similar pressures to anchor their identity on Tagalog fluency. These pressures affect not just celebrities, but also ordinary Filipinos.

J. Pagaduan, 41, is a Filipino American writer of Ilocano descent who never felt the pressure to speak in anything but Ilocano outside the family. However, their Filipino American peers shunned them due to their non-Tagalog background. “The Filipino kids didn’t like me both because I’m Ilocano and they’re not, but also because the little I do speak isn’t Tagalog,” they tell me. “I used to be able to do basic [Tagalog] greetings and stuff like that, but because I called my grandparents and great grandparents ‘Apo,’ they didn’t like me.”

“I like Tagalog as a national language, for the purposes of communication,” says 27-year-old Lo Guan Liong (Adrian Lo), in a mix of Cebuano and English. “What I don’t like is this pressure to make speaking Tagalog a patriotic duty. You speak Tagalog, you’re patriotic. You don’t, you’re not. I really don’t agree with that. I think it’s really stupid.” He supports establishing Tagalog as a lingua franca, to bridge language barriers among Filipinos. But treating Tagalog as superior over the other languages? The polyglot filmmaker has one simple word for it: stupid.

Aliens in our own land

Mass media, such as films, music, and literature, are instrumental in language preservation. While non-Tagalog creatives suffer from a severe lack of funding and support from the powers-that-be, they’re still out there producing art in their mother tongues. But when audiences can’t actually access their works, that’s a huge problem. When I was seeking out films in Philippine languages beyond Tagalog, I was shocked to learn that nearly all of them had been quietly removed from Philippine streaming services.

These include indie hits like John Denver Trending, pretty much the only film in the Karay-a language that I’ve ever seen break into the mainstream. Even after gaining acclaim and awards, streaming sites have wiped almost every single non-Tagalog indie from their catalogues. More disturbing was the fact that even splashier big-studio titles like Kun Maupay Man It Panahon, a Waray flick with Filipino superstar Daniel Padilla in the lead role, could not escape such a fate. As of this writing, there is no longer any way to legally stream the film outside the Philippines. Within the country, the only way to stream it is through Prime Video.

Filmmakers themselves often have no clue that this is happening. Ara Chawdhury has penned and directed some of the buzziest films in modern Cebuano cinema, like the sci-fi flick Miss Bulalacao. A few years back, they also wrote Cebuano dialogue for the Eva Green starrer Nocebo. Despite their lofty credentials their films were removed by Philippine streaming services without even informing them. “The filmmakers themselves are barely getting by, so we have no machinery to push for preservation. We’re barely involved in the conversations about what happens to our films after the producers are done with them,” Chawdhury says. “On the other hand, I also have to accept that if the audiences actually cared about our work, this wouldn’t be the case. I have to accept the inevitability of our own irrelevance.”

Ara Chawdhury (Source: Facebook)

It’s a tragic loss. Films and TV are crucial to language immersion in ways that music, as beautiful as it is, can’t quite replace. Still, that non-Tagalog Philippine songs are constantly accessible provides glimmers of hope.

Musical Education

They’re short and fun and can genuinely be educational. When it comes to music as education, six-member boy band ALAMAT is a trailblazer. The P-pop group debuted in 2021 with “Kbye.” The catchy single talks about a breakup, typical fare for a boy band. However, the members wrote the lyrics in each of their languages: Bicolano, Cebuano, Hiligaynon, Ilocano, Kapampangan, Waray, and Tagalog, a total of seven.

Andrea Anne Trinidad is a Filipino professor at the Ateneo de Manila University. The 28-year-old admits that before she became a Magiliw (ALAMAT fan), she had a proscriptive and prescriptive approaches towards Filipino. It was highly Tagalog-oriented, due to her own purely Tagalog upbringing and the training she’d undergone in college. But the group’s multilingual advocacy made her realize that there was no truly “wrong” way to speak Filipino/Tagalog. She now reminds herself to take into account the context (place and the speakers’ linguistic background) before she corrects their grammar and such.

Another fan, Angela, was born in Samar, Philippines. When she was a child, her family brought her to the US East Coast. Now in her mid-20s, she knows that ALAMAT’s music isn’t the best at teaching the basics of Waray. Still, she says that the group’s songs are the most accessible way for her to stay in touch with her language and roots, beyond conversations with her family. Like her home province’s Samar Pop Festival, ALAMAT’s music offers precious nuggets of Waray culture.

This is true not just for the fans, but also for the members of ALAMAT themselves. Taneo, 25, is the group’s leader and main dancer. Within ALAMAT, he usually sings and raps in Ilocano. But he’s also of Kalinga descent and lived in the US for a while.

ALAMAT (from left to right Mo, Tomas, Taneo, R-Ji, Alas, & Jao) in December 2024 (Photo from ALAMAT's official X account)

In 2023, Dong-Dong-Ay marked the first time that Taneo sang a Kalinga ALAMAT song. The track infuses a Kalinga folk song in the chorus. “I grew up in the Philippines hearing my elders especially my lolo sing it,” he emailed. He says the song means a lot to him, as it brings his Kalinga roots to the modern stage. “Later, living in the US made me appreciate it even more as the exposure of the culture at a young age gave me a whole different perspective on my experience living as a minority in the US.” Performing it with ALAMAT felt like reconnecting with those memories and sharing that heritage with the world, he adds.

Lance Lucas, 38, hails from the Applai, one of the groups in the Cordilleras. He’s the co-leader of IBM’s Indigenous Business Resource Group for ASEAN and Korea. The thought of Cordilleran languages dying scares him, particularly because the Northern and Southern Bontoc languages are currently classed as endangered. ALAMAT’s “Dong-Dong-Ay” gives him hope. “It does keep the language alive, especially [because] the Igorot youth are using it on TikTok.”

A siday (poem) in Waray, by writer Eduardo Makabenta (1885-1973)

Does Any of It Matter?

On the flip side, for some, music continues to be a reminder of discrimination. August is officially Buwan ng Wika (Language Month) in the Philippines. However, some organizations call it Buwan ng Mga Wika (Month of the Languages, plural) instead, in acknowledgment of the Philippines’ linguistic diversity. Lo says that he appreciates the gesture but finds it hollow when laws such as the RA 8491 remain in place. RA 8491 declares that singing the Philippine National Anthem, Lupang Hinirang, in any other language besides the “original” Filipino is punishable by law. Penalties range from hefty fines (from ₱5,000 to ₱20,000) to imprisonment.

Despite promises and efforts to incorporate other Philippine languages in Filipino, in its current form, it’s still effectively Tagalog. Lo protests, “I cannot express my love for my country, in my native language, if I’m not a Tagalog?” He finds the law utterly absurd, especially knowing that it was only put into effect in 1998. Before that, he says, alternate versions of the anthem in other Philippine languages freely flourished.

Harvard graduate Firth McEachern corroborates this. RA 8491 presents the ban on non-Tagalog versions of the anthem as simply a way of honoring the song’s original form. However, the Filipino lyrics were adapted from the Jose Palma’s 1899 Spanish poem Filipinas. “It is yet another irony that the law makes it illegal to sing translations of a song that is itself a translation from another language,” McEachern remarks.

While Lo finds the law absurd, McEachern doesn’t hesitate to identify elements of outright “linguistic fascism” in RA 8491. His country, Canada, allows the National Anthem to be sung in any language. Other nations, like Switzerland and South Africa, also welcome multilingual renditions of their anthems.

But why should we care? Shouldn’t we just let our other languages languish or even die? We’re called Filipinos, so why not just speak Filipino? Even Filipinos might tell you that we have far too many languages, that these would only cause confusion and disunity if allowed to thrive.

In his recent video essay, Kirby Araullo explains that our ancestral languages shaped who our ancestors were, and thus shape who we are too. Losing them would mean losing culture and history. We would be unable to understand ourselves and the people who came before us. To borrow his analogy, a language is like an old home. Our languages may seem shabby and decrepit due to years of neglect, while English is a shiny mansion. Tagalog is perhaps a much smaller house that has been reconstructed in the same neighborhood as English. It’s so tempting to just abandon our dusty old homes. But these unfashionable houses contain generations’ worth of life and love. Once you sell them in hopes of moving to the shinier houses, you destroy entire groups of people, erasing them from existence, desecrating their memory.

“The way my mom makes sinigang when we have kangkong, she removes the stems,” Angela recounts. “She told me before that when I was a child she got upset when our domestic helper included the kangkong in the sinigang.” She explains that the Warays cook it a particular way. “We don’t mix the stems in the broth because they grow in abundance in Samar, or least we had a lot of them growing at my grandma’s house. But our helper’s cooking method was different, because she was Ilonggo.”

“I see the world in Cebuano. My memories are in Cebuano. I think in Cebuano, I feel in Cebuano.

This is what languages are. They’re food, they’re family. In my happiest moments, I see the world in Cebuano. When I look back at Typhoon Haiyan destroying my hometown in my childhood, my memories are in Cebuano. I think in Cebuano, I feel in Cebuano.

Before she died, my grandma taught me that gumamela (hibiscus) is antuwanga in our language, and isn’t that such a unique, beautiful word? An-tu-wa-nga, four syllables, melodious and bright. How can I forget that? How could I let myself forget?

Millions of lifetimes exist within a single language. Even the most rundown houses can be fixed and scrubbed up, if you just try. Knowing what’s at stake, how can you not?

Julienne Loreto (they/them) is a non-binary university student with roots in Bohol and Leyte. They are also a writer whose articles have been published in the prestigious music magazine The Line of Best Fit, as well as the Asian-American magazine JoySauce; their fiction stories have also been selected for publication by 8Letters and sold at the Manila International Book Fair.

More articles from Julienne Loreto