Embassy of Exile: The Filipinos Who Led the Drive for Independence in Washington, D.C., 1941–1946

/Walter Nash, Lord Halifax, Song Ziwen, Alexander Loudon, and Manuel Quezon (standing, right) with Franklin Roosevelt, Washington, D.C., United States

President Manuel L. Quezon had spent decades preparing for this moment. He had led Philippine delegations to Washington in the 1910s and 1920s, pressing for greater autonomy. By 1934 he had maneuvered the passage of the Tydings–McDuffie Act, which guaranteed independence after a decade of transition. He took office as the first president of the Commonwealth in 1935, building a civil service, a judiciary, and a national army. Tuberculosis had weakened his body by 1941, but not his resolve. He told aides: “If we lose Manila, we will carry the government in our hands until we can raise the flag again.”

President Manuel Luis Quezon (Courtesy of the National Library of the Philippines and the Presidential Museum and Library)

Vice President Sergio Osmeña, his longtime rival turned partner, embodied steadiness. Born in Cebu, Osmeña first made his name as a journalist and lawyer. He became Speaker of the Philippine Assembly in 1907, the first elected Filipino legislature under U.S. rule. His partnership with Quezon mixed rivalry with pragmatism; they had once split the Nacionalista Party, but the demands of nation-building brought them together. Osmeña had served as Senate President and Vice President by 1935, respected for his caution and discipline. In 1941 he quietly prepared to assume leadership if Quezon could no longer carry the burden.

Sergio Osmeña — Vice President and later President in exile

Carlos P. Romulo represented the younger generation. Born in Camiling, Tarlac, he had built a career in journalism, rising to editor of the Philippines Herald. His writing on the looming war won him the Pulitzer Prize in 1942, the only Filipino to ever claim the honor. When Japan invaded, Romulo took up arms in Bataan. He escaped capture and reached the United States, where he turned his battlefield experiences into the bestselling I Saw the Fall of the Philippines. Americans embraced him as both soldier and storyteller, and his eloquence soon made him the public voice of the Commonwealth abroad.

Carlos P. Romulo — Journalist, soldier, diplomat, and later UN representative

Joaquín Miguel Elizalde had already been in Washington before the bombs fell. Scion of a powerful sugar family, he became Resident Commissioner in 1938, representing the Philippines in Congress. He had lobbied for sugar tariffs, defense appropriations, and trade concessions. When Quezon and Osmeña arrived in exile, Elizalde provided them with ready access to Capitol Hill and the Roosevelt administration.

Joaquín Miguel Elizalde — Resident Commissioner to the U.S. Congress

Andrés Soriano, head of San Miguel Brewery and one of the wealthiest men in Manila, evacuated with Quezon from Corregidor. He had once been called the “beer baron of Manila,” but in Washington he accepted a new role: treasurer of the Commonwealth government in exile. Soriano leveraged his American business contacts to fund operations, pay staff, and supply relief campaigns.

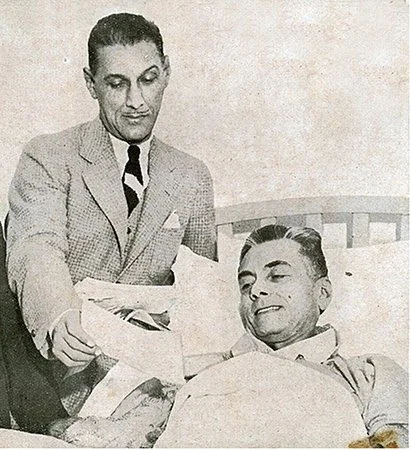

General Basilio Valdes combined medicine and the military. Trained as a doctor in Paris and Madrid, he had served in the Philippine Constabulary and then as chief of staff of the Philippine Army. In Washington he symbolized continuity of the armed forces. He appeared in full uniform at the chancery and in meetings with the War Department, assuring Americans that Filipinos still stood ready to fight.

Basilio Valdes — General and physician, Chief of Staff of the Philippine Army (Photo by Clifford Bottomley)

Manuel Nieto, Quezon’s loyal aide, never commanded headlines, but his presence kept the government organized. A lawyer and fixer, he drafted memoranda, managed files, and arranged meetings. His diligence allowed Quezon and Osmeña to focus on diplomacy.

Manuel Nieto — Quezon’s aide and secretary in exile

Juan C. Dionisio, a younger lawyer from Manila, joined the chancery in 1943. His role extended beyond Massachusetts Avenue. He traveled across the United States to labor camps, plantation fields, and union halls, urging Filipinos to donate wages, buy bonds, and keep faith in independence. For many immigrants, Dionisio became the most personal link to the exiled homeland.

Escape from Corregidor

Their escape from the Philippines tested every resource. In February 1942, Quezon, Osmeña, Valdes, Soriano, and Nieto boarded a U.S. submarine at Corregidor. The cramped vessel dodged Japanese patrols, surfacing at Mindanao after days underwater. From there, they boarded a plane to Australia. Australian newspapers described their arrival as dramatic, with Quezon stepping onto the tarmac pale but resolute. From Australia they boarded a U.S. transport across the Pacific, reaching San Francisco in spring. The San Francisco Chronicle reported their landing, noting the sickly president but emphasizing the symbolism of a government preserved. By train, the party crossed the continent to Washington.

Romulo had reached America earlier, slipping out of Bataan by PT boat and submarine, then flying to the United States. Elizalde was already in Washington, continuing his congressional lobbying. Dionisio joined in 1943, transferred from the Philippines after surviving the Japanese occupation’s early months.

They chose a brownstone at 1617 Massachusetts Avenue as their headquarters. The Philippine flag flew above its entrance, a daily reminder of sovereignty. Visitors described typewriters clattering, telephones ringing, and aides rushing to meetings. American journalists called it the “Embassy of Exile.”

The Philippine Chancery at 1617 Massachusetts Ave., Washington, D.C. (Source: Philippine Embassy)

Quezon, though gravely ill, drove diplomacy. He pressed Roosevelt for assurances that independence would not be postponed. In White House meetings he demanded recognition of Filipino troops as part of the U.S. Army. Roosevelt confirmed the pledge of 1946 independence. In Saranac Lake, New York, where he sought treatment, Quezon dictated The Good Fight, a memoir and manifesto that urged America to honor its word.

Osmeña managed daily work, guiding cabinet sessions and overseeing staff. He lacked Quezon’s charisma but gained respect for his consistency. His calm authority reassured both colleagues and U.S. officials.

Romulo spoke tirelessly across America. At universities he told students that Filipino soldiers had fought for the same freedoms Americans cherished. In Detroit he told factory workers: “When you rivet steel, you rivet freedom in Manila.” In Stockton he told asparagus cutters: “Your dollars are bullets for freedom.” The New York Times profiled him as “a voice for a nation without a homeland.” The Los Angeles Filipino Bulletin reprinted his speeches in full.

Elizalde focused on Capitol Hill. He testified before the House Committee on Insular Affairs, stressing Philippine loyalty and sacrifice. He reminded Congress that Filipinos had fought under the American flag and deserved equal aid.

Soriano raised funds. Fortune magazine featured him in 1942, calling him “the businessman who bankrolls a nation in exile.” He persuaded American businessmen to invest in bonds and supply drives.

Valdes briefed American officers. He described guerrilla activities in the Philippines, lobbied for more aid, and advocated recognition of Filipino veterans. His uniformed presence signaled that the Philippine Army still lived.

Nieto worked quietly but efficiently. He filed cables, typed memoranda, and delivered instructions. He carried Quezon’s personal letters to Roosevelt and handled sensitive files.

Dionisio journeyed to Filipino communities, speaking in Ilocano and Tagalog and encouraging workers to give what they could. Though far from home, their contributions provided both material relief and symbolic unity between diaspora and homeland.

Call to Arms

By 1944 the tide had turned. Roosevelt reaffirmed independence for 1946. Quezon’s illness worsened, and he died in August at Saranac Lake. The San Francisco Chronicle called him “the president who carried his country in exile.” The Washington Post praised his determination. Filipino communities in California, Hawai‘i, and Washington held memorial masses, filling churches and union halls.

Osmeña assumed the presidency without dispute. In October 1944 he returned with MacArthur to Leyte. Romulo, landing with the troops, proclaimed: “We return not as conquerors but as liberators.” The Stockton Record bannered: “Flag of the Philippines Raised in Leyte.” Exile had preserved sovereignty until the flag rose again on Philippine soil.

The call to arms reached Filipino America in 1942. U.S. recruiters opened enlistment for the 1st Filipino Infantry Regiment, drawing volunteers from farm camps, canneries, hotels, and households across California, Hawai‘i, and Alaska. A cadre of Philippine Army and Scout officers who had escaped the islands—among them Lt. Col. Leon Punsalan, Maj. Tirso Fajardo, and Lts. Pedro Flor Cruz and Rafael Ileto—provided professional leadership, with Ileto later distinguishing himself in the daring Cabanatuan raid.

Sergio Osmeña with the First Filipino Regiment

A second regiment followed in 1943, and from these units the Army organized specialized teams such as the Philippine Civil Affairs Units (PCAUs). These bilingual soldiers restored local governance and linked communities with the returning Commonwealth government. Their numbers were small, but their symbolic weight was great: they embodied the bridge between homeland and diaspora, proving that Filipinos in America had fought, bled, and organized for liberation.

The battle for Manila in February 1945 revealed the cost of freedom. Life magazine published photographs of bodies in the streets and churches reduced to rubble. The San Francisco Chronicle described “a capital freed but flattened.” The Commonwealth government returned to ruins.

Loyalty and Sacrifice

Filipino Americans answered with loyalty and sacrifice. In Stockton, asparagus cutters donated wages; in Hawai‘i, plantation workers pledged payroll deductions; in Seattle, longshoremen raised funds for the Philippine Red Cross. Newspapers hailed these efforts as proof that even far from home, Filipinos stood with the Commonwealth in exile. Though modest in scale, their contributions carried symbolic weight, linking labor camps and union halls to the struggle for sovereignty.

When independence came on July 4, 1946, Filipino Americans celebrated in parades and dances across the West Coast, Hawai‘i, and the Pacific Northwest. Veterans marched with flags, bands played both “The Star-Spangled Banner” and “Bayan Ko,” and communities marked the day as both liberation and vindication. Yet joy mixed with anger when Congress passed the Rescission Act, stripping most Filipino veterans of promised benefits. Protests erupted, but the pride of having sustained the flag in exile endured for decades.

By mid-1945 Osmeña had reestablished the Commonwealth government in Manila. He convened legislative sessions in makeshift buildings. Quezon’s portrait hung on the wall as a reminder of sacrifice. Romulo represented the Philippines at the San Francisco conference that founded the United Nations, telling delegates: “The small nation that endured in exile now returns with honor.”

The path to independence accelerated after Japan’s surrender in August 1945. Roosevelt had promised 1946; Truman upheld the date. Congressional debates focused on trade. Businessmen insisted on concessions, resulting in the Bell Trade Act, which granted U.S. investors parity rights in the Philippine economy.

When independence came on July 4, 1946, Filipino Americans celebrated in parades and dances across the West Coast, Hawai‘i, and the Pacific Northwest.

Congress also passed the Luce-Celler Act of 1946, allowing Filipinos in the United States to naturalize, though the quota remained only 100 per year. Filipino newspapers hailed the measure as overdue justice, especially for veterans.

On July 4, 1946, Philippine and American officials gathered at Luneta in Manila. Soldiers lowered the U.S. flag and raised the Philippine flag. Osmeña stood with U.S. High Commissioner Paul McNutt. Witnesses described the president as solemn but resolute. After years of exile, the promise of independence became reality.

American newspapers celebrated. The Washington Post ran the headline: “Philippines Free.” The Chicago Tribune called it “the final step in America’s unique experiment in self-rule.” The Stockton Record declared: “At Last, Independence.” The Los Angeles Filipino Bulletin published photographs of veterans saluting while women in traditional dress danced.

By the end of 1946 the flag over Massachusetts Avenue came down. The Embassy of Exile had achieved its mission. It carried sovereignty across oceans, preserved it in Washington, and restored it in Manila. Its leaders returned to new roles: Romulo at the United Nations, Elizalde to business, Soriano to rebuilding San Miguel, Valdes to medicine, Nieto to private practice, and Dionisio to foreign service.

For Filipino Americans, the embassy remained a symbol. Their wages, their bond purchases, and their military service had built a bridge across the Pacific. Veterans told stories of Dionisio’s visits and Romulo’s speeches. Newspapers later reminded readers that sovereignty had survived in exile when the homeland lay in ruins.

The Embassy of Exile demonstrated that a displaced government, anchored by leaders in Washington and sustained by workers abroad, could carry a nation through occupation and deliver it into independence. It embodied the determination of a people to survive conquest, preserve legitimacy, and claim freedom. And when independence came in 1946, it stood as proof that exile did not mean defeat but continuity.

Alex S. Fabros, Jr. is a retired Philippine American Military History professor.

More articles from Alex Fabros, Jr.