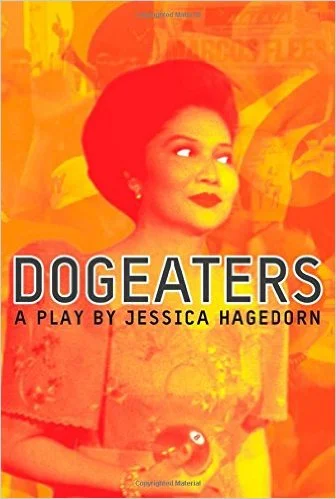

Dogeaters Comes to the Stage

/Jessica Hagedorn' Dogeaters (Source: amazon.com)

The novel was a finalist for the National Book Award and won the American Book Award; it thrust Hagedorn, who was born in the Philippines and immigrated to the United States at age 14, into an international spotlight. She was honored with a Guggenheim Fiction Fellowship, a Lucille Lortel Playwrighting Fellowship, and several residencies at Sundance, where she transformed Dogeaters from the page to the stage.

A wordsmith of many talents, Hagedorn is the author of three other novels, Toxicology, Dream Jungle, and The Gangster Of Love, and the editor of both volumes of Charlie Chan Is Dead: An Anthology of Contemporary Asian American Fiction, and Manila Noir, a crime fiction anthology that won the Philippine National Book Award.

She has also written screenplays, including for director Shu Lea Cheang’s Fresh Kill and the Oxygen Network’s animated series, The Pink Palace and is currently creating a musical play inspired by Lysley Tenorio’s short story, Felix Starro.

Author Jessica Hagedorn (Photo by (c) Miriam Berkley)

But Dogeaters remains an important touchstone, both for Hagedorn and for its witty, vivid depiction of a wide range of Manila denizens – from drag queens to generals, oligarchs to star struck teens, and revolutionaries to velvet-voiced DJs – and their surprising interrelationships.

Hagedorn, who now lives in New York, was recently in San Francisco (her first hometown in the States) to attend early rehearsals of her play, Dogeaters, which will open at the renowned Magic Theatre, directed by Loretta Greco, on February 10.

Hagedorn had just learned that she and the Magic Theatre had been awarded a $50,000 “Voice of California Today” grant from the Gerbode and Hewlett Foundations to create a stage adaptation of her novel The Gangster of Love, which is set in San Francisco.

Over black coffee in a Japantown café, Hagedorn took time out from rehearsals to speak to Elaine Elinson for Positively Filipino about the new production of Dogeaters:

PF: This is the first time the play has been staged in San Francisco, although it premièred almost 20 years ago. How has the play evolved and what is new about the S.F. production?

JH: The play got started in the 90s, when Michael Greif, artistic director of the La Jolla Playhouse, contacted me. He said he loved the novel and wanted to know if I was interested in turning it into a play. I was so surprised. At first I was skeptical, because I always thought of Dogeaters as a movie – it is big, big, big.

I had written plays before, but I had never attempted something this huge. I didn’t know where I would begin, but I was intrigued. He told me if I was unsure, should another playwright adapt the novel. I said no – it’s either me or no one. And he said great!

"Dogeaters" rehearsal. From left to right: Melvign Badiola, Lawrence Radecker, Christine Jamlig (kneeling), Jomar Tagatac (seated), Loretta Greco (director), Mike Sagun, Ogie Zulueta, Charisse Loriaux, Julie Kuwabara, Jed Parsario, Raphael Jordan, Esperanza Catubig. (Photo by Lily Sorenson)

PF: So where did you start?

JH: With Greif’s support, I went to the Sundance Theater Lab in Utah. Back then, Loretta Greco was an up-and-coming director and we went there together with some Filipino actors and other Asian American actors. We had no script, we just had ideas for possible scenes.

Sundance was an important step in the journey of this play because it is a wonderful, wonderful fellowship – you are given three weeks with actors and you can just let your imagination loose, explore and try new things.

After three weeks in the mountains, I left with three or four scenes that were a great beginning.

The play premièred at La Jolla Playhouse in 1998, directed by Michael Greif. He also directed the New York production at the Joseph Papp Public Theater in 2001. It was staged in Manila in 2007 directed by Bobby Garcia.

“In my play, I hope that the audience members are intrigued by what is fact and what is fiction, and think about how fiction might enhance the truth of the event.”

PF: The novel is so sprawling and rich in detail, with dozens of characters in two different time periods thirty years apart. How did you as a novelist figure out how to fit all of that into a two-hour play?

JH: When we first staged it in La Jolla, it was a totally different play. Like the novel it included scenes from both the 50s and the 80s. But it seemed unwieldy, like an overstuffed chicken relleno.

By the time we got to New York, we decided to focus on one central event in 1982 -- the Manila International Film Festival. That’s the pivotal event that brings all these different people together. We cut out the whole earlier era. It was hard, but it was necessary

For this new production at the Magic, I have tightened up scenes, added more Tagalog and written some new scenes – which I think it has made the play clearer and stronger.

PF: Let’s talk about tackling historical fiction. The Manila Film Festival was a very real event, of course, infamous because in Imelda Marcos’s haste to finish the Film Center, the building collapsed, many workers died and were buried alive in the concrete. Some of your characters are absolutely real, like Imelda, and some hew very close to real people (like the assassinated Senator, who seems based on Senator Benigno Aquino) and some are purely fictional. As a playwright, how do you make those choices?

JH: I didn’t want it to be documentary drama, I didn’t want to be beholden to history. I wanted to have my freedom in writing the play. Yes, the opposition Senator who is assassinated was inspired by Aquino, but it is not him. Why do I have to see that in my play? You can watch the news footage. I don’t need to write that tragic story for you.

It’s kind of like E.L. Doctorow’s Ragtime. That novel was a revelation. Doctorow was adept at portraying real historical characters -- even I recognized these giants he had running around from American history: like J.P. Morgan, Harry Houdini and Stanford White. But then he created a fictional family, and they were our way in to that world. He included events we recognize from history and events that were made up, and conflated them. He mixed it up. That’s what artists can do!

In my play, I hope that the audience members are intrigued by what is fact and what is fiction, and think about how fiction might enhance the truth of the event.

From left to right: Melvign Badiola, Christine Jamlig (kneeling), Mike Sagun, Ogie Zulueta, Jomar Tagatac (seated), Raphael Jordan, (seated at table). (Photo by Lily Sorenson)

PF: Who are the influences on your writing?

JH: Latin American writers are my true inspiration.

I always wanted to write a novel about “my” Philippines, but I had no guidebook about how to do it and really capture the wackiness and complexity of the culture until I read authors like Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Manuel Puig, who wrote Kiss of the Spider Woman.

Marquez shows you the expansiveness of the world of the imagination. Half the names he uses are the names of actual people, but you think they are made up. He writes about historical incidents, and the reader thinks they are fiction. You realize the world is totally surreal.

Marquez portrays the richness of the culture: he doesn’t judge, there’s no moralizing. He just lays it out. I think I learned a lot from reading the Latin Americans.

PF: Who are your favorite Philippine authors?

JH: I really love Bienvenido Santos. I just wrote an introduction to a new edition of his short story collection The Scent of Apples. I’m so pleased that they are publishing this beautiful new edition because I think he’s been forgotten.

I also admire a new writer named Mia Alvar, who has published a collection of stories called In the Country, and I love many of the stories of NVM Gonzalez.

PF: There was – and probably still is -- controversy on the title Dogeaters. How do you respond to criticisms that it is derogatory or racist?

JH: The title is controversial. I think I knew I would open a big can of worms when I chose it. I wanted to grapple with that pejorative term and make it stand on its head. I could have easily called the play something really pretty and it would still work – something like Lost Paradise or Paradise Lost – and everyone would have been fine. But Dogeaters is not a pretty story. There are beautiful moments in both the novel and the play, but there are also some ugly situations.

And there’s something about me that ‘s always up to some mischief.

I don’t want to sound glib. I know the term causes people pain, and I am so sorry it does. My decision to use a title that makes a lot of people cringe is kind of like holding a mirror up -- and questioning what is this shame that we all have? What is this feeling that we are never good enough, what is that rage, what is our uncomfortable relationship with the United States and Americans, the white Americans?

There was energy and anger behind my choice of that title, and I want to honor that.

One of the greatest compliments I’ve received is from novelist Marlon James [the Jamaican author who won the 2015 Booker Prize for A Brief History of Seven Killings] who said that Dogeaters is the best novel about Jamaica that’s ever been written. And I thought, he sees what this is all about, and understands what I am trying to do.

PF: The current production at the Magic is a major undertaking -- has 15 cast members, most of them playing multiple roles. The staging is also complex, with scenes in a Tondo hovel, a fancy hotel, a posh golf course, a guerrilla camp in the mountains and a tawdry night club, just to name a few. How is it going?

JH: This production is very challenging, but I feel that with director Loretta Greco, the play is in very good hands.

And this is giving a very talented pool of Filipino actors on the West Coast a great opportunity, just as it did in New York. Some of the actors play many roles -- this is ridiculous, even for the greatest actors! They work so hard, and they have to do these quick changes. But that’s the fun of it, the excitement. They are having the time of their lives! It’s why you want to be an actor.

The casting also allows the audience members to see the flip side of different characters – the drag queen is also the army general, a beloved Lola is also glamorous movie star.

I hope this play brings a Filipino audience to the Magic Theatre, but that will also depend on the outreach. We want a mixed audience, we want everyone to come to see the play.

In New York, we had full houses every night. The Public even had two extensions. And we’d love the same thing to happen here.

PF: Your book came out only a few years after Marcos was ousted from power. The memories and the feelings were still raw. What do you think audiences today will think?

JH: When the play was first produced, these experiences were still very fresh. Now, there is a whole generation of youth for whom this is not even recent history – it’s something their grandparents lived through. I feel that sometimes in rehearsal we’re giving history lessons, because we want the cast to understand deeply what that time was like.

And we have to ask ourselves, why does this play still matter. Many of us are familiar with the maxim, “Those who don’t learn from history are doomed to repeat it,” but George Bernard Shaw had a more existential thought that I like: “We learn from history that we learn nothing from history.” Maybe playwrights are more cynical and bleak than most. But, hey, I didn’t set out to moralize, proselytize, or write some sort of “lesson” play. All I can hope for with the San Francisco production is that a new generation will be moved by the plight of my characters, and that they will continue to ask questions about the world and their amazing, complicated culture.

The Bay Area Premiere of Dogeaters by Jessica Hagedorn, directed by Loretta Greco, will open on February 10 and play through February 28 [with preview performances starting on February 3] at the Magic Theatre, Fort Mason Center, San Francisco.

Order tickets on line at www.magictheatre.org or call the box office at 415-441-8822. Positively Filipino readers can get a 15% discount on tickets purchased prior to February 2 by using the code DOG15.

Elaine Elinson was a reporter for Pacific News Service in the Philippines; she is coauthor with Walden Bello of “Development Debacle: The World Bank in the Philippines”, which was banned by the Marcos regime.