Departure Date 1973.August.05

/José Esteban Arcellana with mom (Photo courtesy of José Esteban Arcellana)

They were cheap suitcases, soft-sided vinyl in mismatching colors that I got in Divisoria or Quiapo, I don’t remember, and they were only slightly more than half-full. Clothes, mostly, some pants that were probably too tight and shirts that were probably too small. One dress-up outfit, you never know.

My older siblings were already in the States, in medical specializations and being doctors, and I was up next, so to speak, to seek my fortune in graduate school abroad.

Later, when it was their turn, my younger siblings also left. We were that kind of family -- going to graduate school, preferably abroad, was an expectation as normal as continuing to high school after your elementary school graduation. I thought all families were like that, because when you are a kid you think that you have a normal family. There are six of us, and half of us ended up returning to the Philippines and half of us stayed away, for various reasons; so we are split across the Pacific Ocean. That happened later.

On this day, only my younger siblings were still home. My youngest sister sat in my room watching me pack, not saying much. She was not quite ten years old. She polished my black leather belt as she sat there, then gave it to me to pack. I rolled it up around its buckle and tucked it into a suitcase.

My younger brother, then 14, was reading, sitting in the living room upstairs, waiting for the moment when we would all pile into the station wagon and head for the airport, except for my younger sister (18 that year) who was not going to the airport with us. I think the idea was that someone had to stay home (taong-bahay), but really it was because there wasn’t enough room in the car for everyone, because my girlfriend at the time was of course also going to see me off.

When we left the house, my sister who was staying home was doing the dishes; she interrupted her chore, dried her hands on a dish towel, and gave me a hug. She cried a bit, but that was all I saw because we were on our way to MIA, Manila International Airport.

My girlfriend was wearing a short white dress with quarter sleeves that had Virgin-Mary blue elastic bands above and below the elbow. I had not seen that dress before, and she looked like a bride, which I suppose she would have been if I had not been leaving, instead, for graduate school.

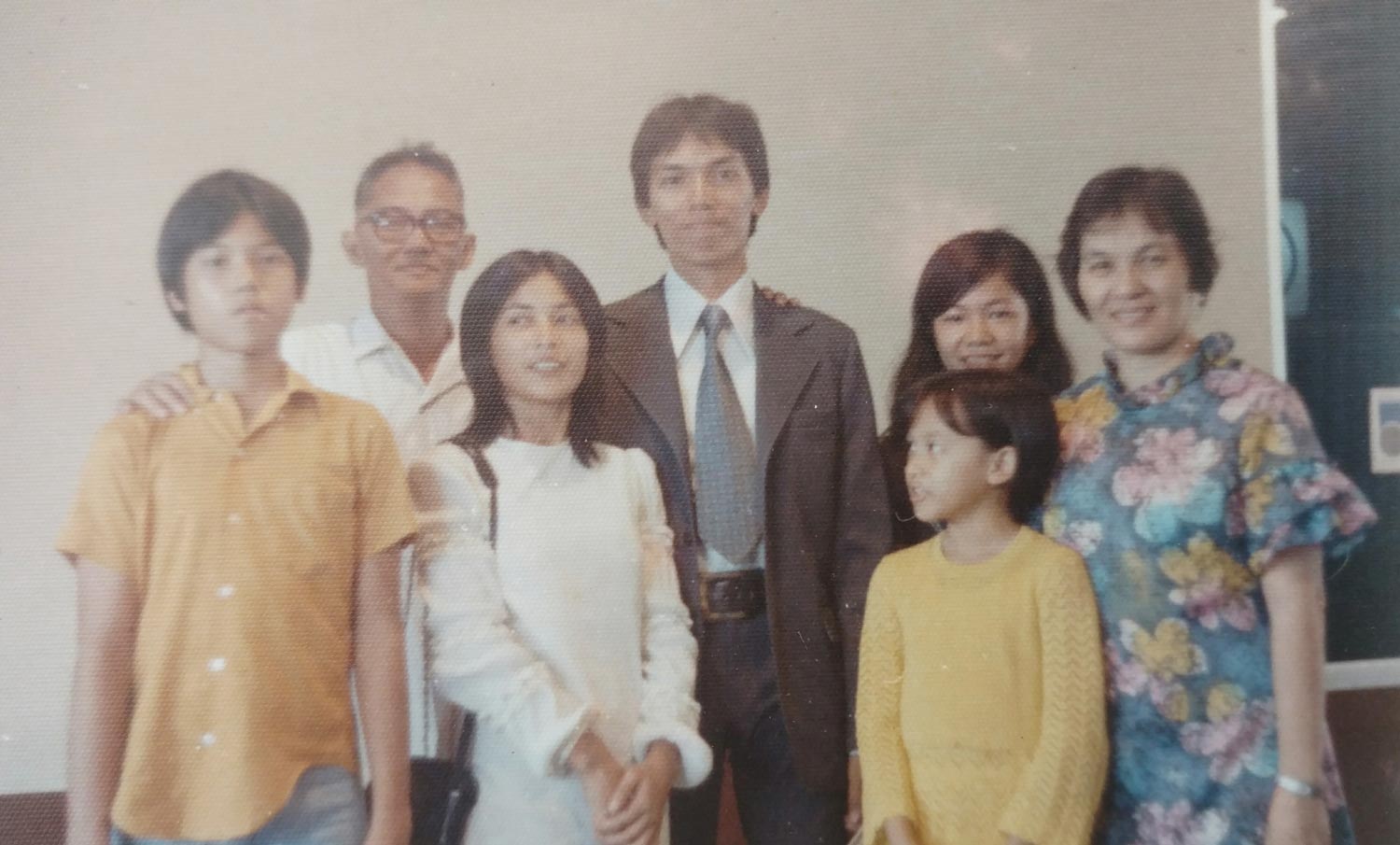

José Esteban Arcellana and family (Photo courtesy of José Esteban Arcellana)

Traffic to the airport was not bad, not anything like it is now, and we got there from our home in Diliman in less than an hour. There was construction going on, which now seems like a perpetual state at MIA, and my terminal was not in the main building but in a smaller one, where temporary check-in counters were set up, and passengers would take a shuttle bus to the plane.

We unloaded my bags, checked them in, and I went through the usual security checks at the time, passport and visa, and so on, all of which in my memory seems like nothing now, smooth as getting on a city bus compared with how onerous and unfriendly the process has become.

When there was nothing left to do and I was waiting to be told that the shuttle to the plane was boarding, we stood around in the waiting area — my parents, my younger brother and my youngest sister, my girlfriend — not saying much, taking a few pictures, and then it was time to go.

“It would be six years before I returned for a visit, and I never came back to stay. On that day I had no intention of not coming back, but life and history happened.”

I said goodbye to my brother and my sister first, then my mom, then my dad, and last my girlfriend. I hugged and kissed my mom and my siblings, who were crying, and did the same with my girlfriend (though it was a different kiss, of course); and I only shook hands with my dad, but he gave me the moment that I took away to keep for as long as I have any memories of this day. He was tearful when he shook my hand, and I had seen him do that — shed tears — only one other time in my almost 23-year-old life. It was a bit of a shock for me. I was still in shock as I said goodbye to my girlfriend, and as I turned away to join the line for the shuttle, my last look, almost in disbelief, was at my father.

It would be six years before I returned for a visit, and I never came back to stay. On that day I had no intention of not coming back, but life and history happened. As much as I was going to graduate school, I was also escaping a dictatorship that was doing its worst to destroy my generation.

Every person who has left his or her first country to move to a new one will have various complex reasons for doing so; but each one will tell you that if there were a way to get a better education, make a living, live in peace, feel free to exercise basic rights, and not be killed or compromised while simply trying to have a decent life, then we would have stayed. In a heartbeat, we would have stayed, but on that day, I left.

I kept it together pretty well until my plane reached cruising altitude and I happened to be checking my jacket pockets to make sure I had everything and discovered a couple of farewell notes from my sisters; then I couldn’t any longer.

But I was fine by the time I landed at Haneda, eager to discover what lay ahead, knowing at some level deeper than my excitement, but not as deep as my grief, that the next day would indeed be the first day of the rest of my life.

After a 30-year career in user interface design and high-tech product design management, José Esteban Arcellana is seeking new opportunities in writing, teaching and building the beloved community. He lives in the Sierra Nevada foothills with his wife, five cats, two guitars and a ukulele and a Labrador Retriever.