Death of an Army

/Filipino and American prisoners of war at the start of the Bataan Death March (Source: AP)

By the end of March [1942], the USAFFE was no longer an army. Just a collection of sick, hungry, forsaken men in defensive positions across the peninsula from Manila Bay to the China Sea. Divisions were down to 1,500 men at most; regiments to 500 effectives. That is, if one can call an ill-fed, ill-clothed, ill-armed, ill-everythinged civilian-soldier combat effective. The famed Philippine Scouts and the all-American regiment had been whittled down too ― the Scouts by combat casualties, the Americans by disease.

Whatever was left of the valiant Cavalry, the rear guards of all the retreats, had become dismounted infantry. Its mounts and pack-mules had been converted to tapa (dried meat), tasty enough if pungently horsey and slightly wormy.

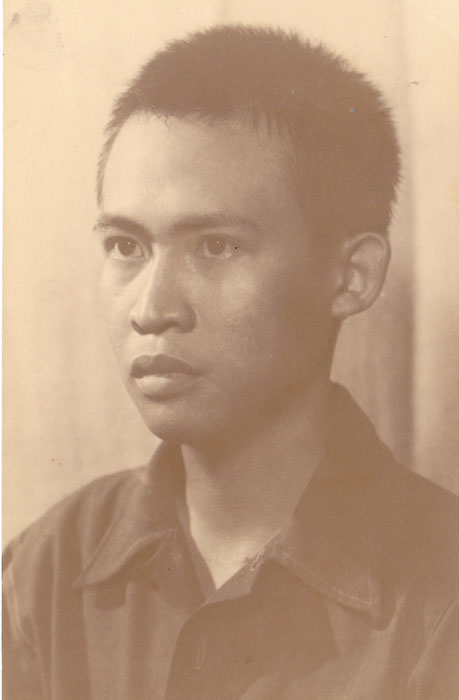

Tony Nieva as a cadet.

It had been over on April 9, two days ago. Tony had known even then but refused to admit it, nursing still a forlorn hope for a miracle. He had known that night when his section had been sent out to contact the battalion command posts (the signal wires had been out since dusk and the men had faded into the night) and verify what the Colonel suspected.

On the reverse slope of the San Vicente ridge, they had come upon the 1st Battalion command posts’ wanton disarrays ― the dug-out churned by a giant hand; equipment and corpses strewn about like post-typhoon debris in a squatters’ barrio. Only the Major seemed relaxed, lying on his back, eyes closed in peaceful slumber…except he had no legs. Tony was thankful for the darkness.

Somewhere along a trail (littered by once-upon-a-time familiar faces), Lt. Dima lay on his side, bent knees and arms enfolding his groin, crooning a death lullaby to himself.

“Patay na ‘ko (I’m dead already),” his last gasp between flickering life and recognition in the dimming eyes. Just three words, his ultimo adios.

By midnight, the battalions had evaporated. In the Regimental Command Post, the Colonel to the assembled staff said, ”It’s over. Save yourselves. Good luck.”

Three phrases, the Regiment’s elegy.

What else could have been said?

The death of a man or of a regiment is just a statement of fact.

Tony Nieva after his release from Camp O Donnell.

What is the death of an army like? There is no cohesive picture, just a series of disconnected rushes of a grade-B horror movie. It is the obscene grimace of a blackened face peering up from a foxhole; a spread-eagled figure on the ground too exhausted to give a damn; a half-hearted stand atop a vantage knoll, firing without aim or conviction at scattering dolls on the trail below; an old-timer noncom at the wheel of an un-startable truck, teary rivulets of frustration winding down furrowed cheeks; a haggard general brandishing a rifle at zombies with glazed eyes and deaf ears ― King Canute trying to stop the tide, confident still in the power of his stars; a bloated carcass bobbing on a lively stream (was it man or beast?); an anti-tank squad calmly dismantling its gun, idly watched by civilians squatting under a shadeless tree; the stench of frying meat from a burning tank; hollow-eyed men beside roadsides munching the visors of their coconut helmets like children chewing handkerchiefs to still the uncontrollable trembling. And white flags blooming in the jungle green.

Cayab was the first, bullet in the thigh. From A STRAY bullet!

“Against this tree?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Riple? Bala? “

“No need, sir.”

“Cigarillo? “

“Salamat, sir.”

“Canned goods?”

“Have got, sir.”

“White flag?”

“Undershirt, sir.”

“Adios, bata.”

“Adios, sir.”

So they walked on, without looking back. Except Pedro, once, twice, then running back. Adios Pedro also. No greater love.... in deed.

Only six now, they fell in with a rear-guard unit shuffling down a trail with fatigue-heavy legs, once a Company, now just twenty Philippine Scouts led by an old, bony-faced Sergeant.

“Your officers?” Tony asked.

“Ours dead, others left with the other ‘Mericans,” the old Sarge replied with an “I-don’t-care-now” voice.

Above a trail junction, they halted. The men deployed automatically if lethargically out of habit. Two grass-thatched tanks nosed uncertainly at the road fork, their gun-snouts sniffing around as if testing the wind; the supporting infantry milling about behind them, their rotten-vegetable sweat-smell polluting the morning breeze.

“Let them by,” Tony told the Sergeant who nodded, a flicker of relief in his eyes at Tony’s tone of command (he was not wearing any insignia of rank).

Later at sunset at another hummock, Tony passed around cigarettes broken to half-sticks and lit his own.

“Light up before they come,” Tony said noting the hesitation in the Sergeant and the men. They had just fired two volleys at tiny hunchbacks on the bald hillock across the vale.

“Go ahead, light up; they know where we are,” Tony repeated, ”last smoke before dark.”

Moments later, probing whizzes. The men flattened, pressed closer to the contours of the knoll, still sucking on the last millimeters of the butts (the last cigarette before the firing squad?). Tony, cuddled in the embrace of a shell hole, felt the old Sarge tap his shoulder.

“Niol, you and your men go now, we Scouts take care of that,” pointing at the enemy’s direction.

“Adios, ‘Gen,” Tony said without discussion but with wonder at the old soldier’s undying pride.

On and on they walked. To somewhere, anywhere, just to get away. Passing the vanquished on the waysides with white-pennanted sticks; passing the lifeless in ditches looking happier than the living; passing ammunition and fuel dump volcanoes (the tremors of their eruptions more earthquakey than nature’s own). Passing by a 155 crew still firing (oh yes, there were still a valiant few); passing gangrene-stenched hospital tents and nurses, smiles betrayed by apprehensive eyes (and valiant women too).

Passing by an American field kitchen, the mess sarge Manila-old-timer friendly.

“Chow? Got stew.”

“My men too?”

“Help yourselves.”

Hard bread and watery stew. Tasting tinny but good, so good, after nothing.

“Thanks.”

“For nothing (in Spanish yet). Por nada.”

Tony Nieva years later

Por nada, the men went on dying. The Japanese bombing, strafing, machine-gunning, and bayoneting relentlessly. Despite up-raised hands and cast-down arms. By orders or from anger.

The enemy, wound and scar and memory of the USAFFE’s past routs and unexpected revivals still bitter fresh, continued the killing. No chances. No quarter. No mercy. ”Mercy is to prolong the war.” It was the Japanese, this time, who still expected miracles.

In the face of the anguish around him, General Edward P. King, the newly appointed Commander of the Luzon Forces (one of four subterfuge titles created to stall the impending surrender to the Japanese, because no single commander could negotiate the surrender of all the Philippine forces) ignored the foolish, unrealistic order to counterattack.

It was all quiet on the Bataan front save for the sporadic booming of ammunition and fuel caches, the final defiant protests against the victorious foe. The last miles to Mariveles were junkyards of broken vehicles, broken armaments, and broken men with broken dreams. The defeated, like beggars in churchyards on St. Anthony’s Tuesdays, decrepit, unwashed, in rags, huddled in dejected clusters. Many sprawled in the dust ambiguously dead or alive.

That Easter Week, the USAFFE Luzon Force died. The once-proud army that had decimated the original invasion forces had crumbled to scattered fragments of broken men. On the 9th day of April, 1942, the “largest force the United States had ever lost” surrendered.

There were no recriminations, however. ”Each man had done his best, and none need feel shame.” The battling bastards of Bataan had been overcome as much by Japanese arms as by starvation and disease. From the halls of the U. S. Congress, the British Parliament, and the “free world” poured paeans of praise — Bataan was the shining symbol of defiance and hope in those dark days of defeat; the defenders’ sacrifice had gained precious time for the Allied counterattack; the “free world” owed them an eternal debt of gratitude and so many more words to that effect.

Sadly, so quickly forgotten. For, when the “forces of democracy” finally triumphed, most of the Filipino battling bastards remained illegitimate sons, still with “no papa, no mama, no Uncle Sam” — and no U.S. back pay either.

Sic transit gloria mundi.

“Death of an Army” is an excerpt from the late Antonio A. Nieva’s book, Cadet, Solider, Guerilla Fighter (available on Amazon.com), a personal history of a Bataan Death March survivor and Hunter ROTC guerrilla. Nieva (Tony) was an ROTC officer at the Ateneo de Manila when he was recruited to join the USAFFE’s mobilization in preparation for the Pacific War. After his release from the Japanese POW Camp O’Donnell, he joined the Hunters-ROTC.

He was awarded the Bronze Star Medal of the U.S. Army for his “marked contribution to the defense of Bataan.”