Countdown to the Revolution Part 2: The Election and its Aftermath

/Doy Laurel and Cory Aquino campaigning during the 1986 snap election (Source: AFP)

At the center of it all was the David vs. Goliath battle between a politically savvy strongman and – as we later realized – just as politically savvy widow on whose shoulders we have placed our collective hope for a new historical direction.

On the surface, the snap election of ’86 was a puzzler. From the American government to experienced political pundits to traditional politicians and even to the extreme Philippine Left, it was just unthinkable for this politically inexperienced woman armed ”only” with a widow’s righteous anger and the support of an unorganized mass of victims and the discontented to even hope to dislodge a dictator, aging and ailing he might be, who had been in power for 20 years and had a formidable, well-oiled political machinery with a humongous war chest behind him

But since August 1983, when the widow’s husband, Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino was assassinated, the political balance had gone awry, the center no longer held. The anti-Marcos forces of various persuasions were slowly coalescing into a previously unthinkable unity, while the KBL, Marcos’ party, was suffering through demoralization and dissension within its ranks. One need not scratch too deep for the surface to crumble into dust.

President Ferdinand Marcos chooses Arturo Tolentino as his running mate.

Between December 1985, when Marcos announced the snap election, and February 1986, when it took place, were some of interesting behind-the-scenes stories that ultimately contributed, directly or indirectly, to the EDSA People Power Revolution later that month:

Imelda’s Choice: Arturo Tolentino, 75, former senator and a brilliant Constitutional lawyer, who at various times during Marcos’ 20-year reign was a critic of the regime, was chosen as the running mate of Marcos. His selection almost triggered a near-rebellion in the KBL ranks by those who were hoping to be anointed. Why Tolentino? Officially, because Marcos wanted a “credible” candidate and Imelda wanted a KBL victory in Metro Manila, Tolentino’s bailiwick. But more than that, Tolentino, at 75, was too old to be a threat to the first lady should she run for president in 1992, and too unpopular within the KBL to even get a nomination for the presidency in case Marcos would not be able to finish his term. Labor minister Blas Ople, one of the disappointed hopefuls, confirmed the speculations obliquely. Citing that “actuarial considerations” had gone into the decision, he lamented, “Our misfortune is that we belong to the same generation as the first lady.” (Another hopeful, Governor Ali Dimaporo of Lanao del Norte, was so disgusted with the choice that he threatened to hold clean elections in his province, a news report quoted him.)

The Enrile Factor: Juan Ponce Enrile, the defense minister and once the martial law administrator and Marcos’ most trusted henchman, eventually became a Palace outsider following his verbal jousts (some insiders said “shouting matches”) with Imelda Marcos. Feeling threatened by what he termed the Imelda-General Fabian Ver (the Armed Forces chief of staff) tandem, Enrile beefed up his security forces by recruiting some of the top graduates of the Philippine Military Academy (PMA). These officers formed the core of the Reform the Armed Forces Movement (RAM) whose planned coup d’etat led to the EDSA uprising.

Intense Intramurals within KBL: Faced with a snap election they didn’t approve of, KBL factions appeared. The technocrats wanted a “professional” campaign strategy and a “credible” victory while the traditional politicians were angling for greater control of campaign logistics for a Marcos win at any cost. Then there was the conflict between the KBL leadership and the Marcos family; when the dust of their combat settled, KBL stalwarts Nicanor Yniguez (then the speaker of the Batasang Pambansa), Blas Ople and Jose Roño, among others, were named campaign managers, but the funds and other logistics were controlled exclusively by the Marcos children, Imee and Bongbong, and son-in-law Greggy Araneta. The arrangement, as Philippine traditions go, was an affront to the elders, betraying what insiders described as the ruling family’s basic distrust of KBL officials who had always supported them.

Rumblings among the rank and file: Shock at the opposition’s expose of Marcos’ wealth, disillusionment over the Aquino assassination and the acquittal of the military, abuses by the armed forces in their areas that were just ignored by the leadership – these were among the reasons that Marcos’ hold on the KBL rank and file was fraying, and a frayed core was a weak core.

Marcos’ state of health: Obviously ailing, Marcos’ campaign appearances were few and far between. In one sortie, his hand bled and he was reported to be on the verge of collapse. When he next appeared in public after a few days’ rest, his bleeding hand was swathed in bandages. He was obviously in extreme pain and discomfort; in fact, backstage comfort rooms had to be built for his exclusive use.

The Opposition

Armed with high expectations, a moral ascendancy, and a lot of prayers, the Aquino-Laurel team revved up its campaign engine with enough media hoopla, only to see it falter and sputter soon after. The Inadequacies were appalling to experts in traditional campaigning. Consider: 1) There was no campaign manager, only Manila-based campaign coordinators. Cory Aquino insisted on this arrangement because she believed that the people themselves should band together to support her, independently of one another. Additionally, there was hardly enough money. Campaign leaders had to raise funds. 2) Beyond or maybe because of the inexperience and lack of logistical support, the Aquino-Laurel campaign suffered from poor coordination. In their provincial sorties in the early days of campaigning, local leaders were not informed of their arrival. They had to ride an open jeep through empty streets; some stops had to be canceled because opposition leaders were bickering; on others, the candidates were not given enough briefing on local realities that they failed to address them in their speeches.

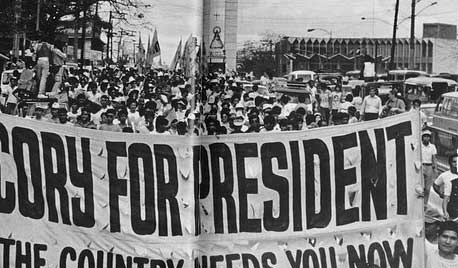

One of the many street rallies during the campaign.

Despite these problems and because she was riding the tailwind of change, Cory Aquino proved to be the phenomenon of the season. Drawn by her simplicity and sincerity, crowds in the hundreds of thousands all over the country waited for hours to catch a glimpse of her and hear her talk about the agonies her family went through during Ninoy’s incarceration.

The personal tale of woe she used to the hilt proved to be highly effective. The masses wept and identified with her and her sufferings under the dictatorship, and pledged to protect and support this valiant woman who had very gallantly taken up the cudgels for them. The strategy defied existing conventions of a presidential campaign, and Marcos’ usual macho bluster only highlighted her intention of presenting herself as the “complete opposite” of the strongman.

Yet she did not promise much and in fact showed her unconventional side by limiting her campaign promises to those she knew she could fulfill. Her economic platform basically maintained the system of free enterprise, aided by “less government in business.” Her political platform was equally stark – the dismantling of the structures of dictatorship to pave the way for a genuine democracy.

An unprecedented feature of the Aquino campaign was the proliferation of campaign materials which, unlike those given free by the Marcos camp, were for sale. Ambulant vendors all over the country were earning quite a sum through the sale of yellow memorabilia – Cory stickers, pins, dolls, hats, umbrellas and the like. Money from the sales beefed up the opposition coffers but the more important effect was the sense of identification and participation in the Aquino-Laurel candidacy of people from all sectors. This proved invaluable in priming the people for the final confrontation with the dictatorship.

As the Aquino juggernaut gained strength even among previously skeptical sectors, including the US government, defections from the Marcos camp began. Some were high-profile figures such as Letty Ramos Shahani and Antique’s Governor Enrique Zaldivar. Others were planning their moves quietly; Roilo Golez, for example, who was probably the only agency head who gained widespread admiration for actually getting the Post Office to deliver mail quickly nationwide, was surreptitiously emptying his office of his personal belongings, except for his photos and paintings because it would have been too obvious. He was going to announce his resignation on February 22.

The international community of Filipino expats actively participated as well, raising funds and providing much needed logistics to the Aquino-Laurel team. And the Catholic Church issued a pastoral letter invoking its faithful not to sell their votes but rather to follow their conscience, a thinly cloaked rebuke to the ruling party.

“Another hopeful, Governor Ali Dimaporo of Lanao del Norte, was so disgusted with the choice of Tolentino as Marcos’ running mate that he threatened to hold clean elections in his province, a news report quoted him.”

The Left’s Dilemma

Faced with the tremendous outpouring of popular support for Aquino’s candidacy, the broad spectrum of leftist organizations split into two: the boycott proponents (the National Democratic Front and the Communist Party) and those who called for participation in the election campaign. While there was no denying that it was the revolutionary forces that carried the torch of active engagement against the regime even at its most repressive phase, their leaders, like Marcos, did not realize that the countdown for the dictatorship had begun. This major “tactical error” would cost the extreme left some of its most ardent supporters and isolation from the anti-dictatorship mainstream.

As the day of reckoning drew near, the mood of the country grew increasingly frenzied. International observers, notably some top US legislators like John Kerry, and foreign correspondents from various countries started arriving in droves and fanning out to various areas as their observation posts. The NAMFREL, the nationwide watchdog of thousands of concerned citizens, set up its quick count system which, though unofficial, would manage to limit incidents of miscounting. Likewise, tens of thousands of volunteers all over the country promised to be watchful of fraud and intimidation, with direct lines to media outlets to report incidents.

The Marcos camp likewise pulled out all stops to assure its victory, from actively supporting the CPP-NPA-NDF’s boycott to airing elaborate radio and TV commercials denigrating Cory’s intelligence and inexperience. Survey results showing a formidable Marcos-Tolentino lead were likewise distributed to the media.

Two days before the end of the campaign period, the opposition called for a miting de avance (final rally) at the Luneta grandstand. At first, the Aquino ringleaders were apprehensive about their ability to draw a crowd of respectable size. But their presidential candidate was adamant. “If we cannot fill up Luneta then this whole exercise is useless,” she asserted. She was right. The average estimate of the crowd that night was a million cheering, praying Metro Manilans chanting Cory! Cory!

A day later, it was Marcos’ turn to speak before a considerably smaller crowd of several hundred thousand who listened to his final harangue and his promise to restore law, order and discipline after the election, a clear allusion to his 1972 martial law proclamation. When it rained, the dictator lost more than half of his audience, as recorded by the media. His clock was ticking its way to the final hour.

February 7, 1986

Everyone expected massive, fraud, intimidation and vote buying on election day, and no one was disappointed. What caught the opposition unprepared, however, was the massive disenfranchisement of registered voters by the COMELEC, a previously unheard of tactic employed with impunity in opposition bailiwicks including Metro Manila and neighboring provinces. The 850 foreign correspondents and hundreds of local journalists saw it for themselves: Thousands of citizens who had previously voted in their precincts suddenly found their names missing from the voter lists.

Redress was possible, true, but it required the disenfranchised to go to a judge, execute an affidavit and bring it to the election registrar who would then issue an authorization. A few were able to vote that way but thousands had to give up, either because they didn’t have the means or the patience for the tedious process, or because no judge was available in their area.

If the intention was to reduce the number of Cory votes, it succeeded. The NAMFREL would later estimate that over a million registered voters were unable to cast their votes. But the evil scheme backfired – the disenfranchised were furious and, with strengthened resolve, pledged to escalate the struggle to topple the dictatorship.

On election night, the NAMFREL quick-count figures showed Aquino and Laurel commanding a consistent lead. Less than 24 hours after the polls closed, the Aquino camp decided to seize the initiative; the housewife who dared challenge strongman claimed victory for herself and the Filipino people.

The KBL was unfazed. Relying mainly on the official COMELEC tabulation which, for some reason, the returns were coming in mere trickles, Marcos proclaimed himself the winner, confident that he would win a margin of 1.2 million votes.

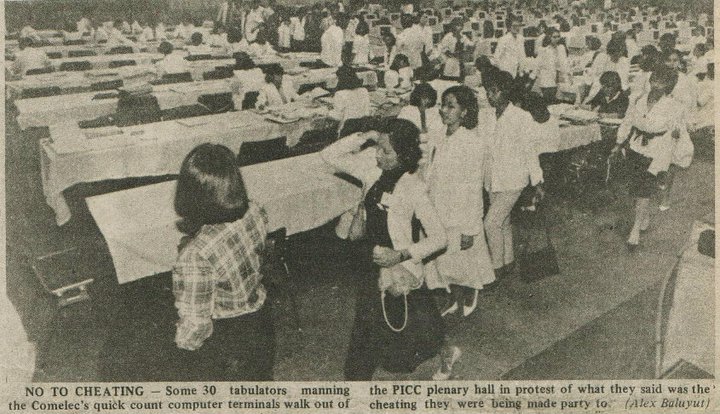

The nation didn’t sleep that night or in the succeeding nights. Two days later, 35 computer programmers assigned to the COMELEC tabulation center walked out of the hall to protest what they termed the election body’s attempts to manipulate the results shown on the tally board. Even Ambassador J.V. Cruz, an avid Marcos supporter, condemned the manipulation of the COMELEC tabulation and supported the programmers’ walkout during a TV appearance.

A newspaper clipping of the tabulators walking out to protest the cheating at the Commission on Elections (COMELEC) (Source: Definitely FIlipino. Photo by Alex Baluyut)

As confirmed later on by my personal interviews with Linda Kapunan, who by virtue of seniority became the group’s unofficial spokesperson, the dramatic move was a spontaneous one, decided only a few minutes before it actually happened. The programmers, most of them young and totally scared, later issued a statement that they were not siding with any candidate. Rather, they decided they could not live with the realization that their skills were being used to distort the truth.

A week after the voting, there was still no official winner declared, throwing the already tense situation into further agitation. Within that week, President Ronald Reagan, a personal friend of the Marcoses, made a major blunder. Ignoring the concerns of Sen. Richard Lugar and other US observers on the ground about the slow COMELEC tabulation, Reagan went ahead and announced that both sides appeared to have committed fraud.

His statement, beamed via satellite, elicited strong negative reactions not just from the Aquino camp, but also from the American media in Manila and the American public itself, which had a ringside view on TV of the election and its aftermath. High-level US embassy officials threatened to resign en masse.

As a result, Reagan had to send his personal emissary, Philip Habib, to Manila a week after his statement, to try and broker a power-sharing compromise between the two camps. The US government’s main concern was to protect its military bases and American business investments; a prolonged chaotic situation would be threatening to its interests.

President Ronald Reagan's personal emissary, Philip Habib (Source: Corbis Images)

Habib seemed to have convinced Marcos of the power-sharing arrangement (which essentially asked that Cory Aquino concede and wait until the next election to succeed FM). After all, Marcos still had the martial law card in his hands. The American envoy however hit a brick wall with Cory Aquino. As lawyer Rene Saguisag, who was Cory’s spokesman, recalled, Cory told Habib straight to his face, “I won and I will take power.” The emissary had to fly home empty-handed.

Civil Disobedience

She will take power but how? The opposition was in a major dilemma. Already the weak-kneed among them were pushing for the Reagan-Marcos gambit towards political accommodation. Laurel, who had been quiet through all these tug-and-pull, was willing to give a coalition government a try. Everyone knew that Marcos could just wait it out, and the tense situation would peter out in his favor.

On February 20, the KBL-dominated Batasang Pambansa (parliament) declared Marcos president-elect. The move triggered a heated debate and a walkout by 57 oppositionists. On the same day, Cory Aquino was similarly proclaimed in a “people’s victory rally” at Rizal Park. About two million gathered that afternoon to affirm that “Cory is our only president” and listen to her instructions for a civil disobedience campaign.

The stalemate continued as NAMFREL released its counter-tally refuting the Batasang Pambansa figures. The US observer delegation likewise issued its report to Congress saying that the proclamation of the Philippine parliament of a Marcos-Tolentino victory was questionable and did not reflect the will of the majority.

Cory Aquino’s civil disobedience campaign involved the boycott of crony firms and products, including San Miguel Beer and Coke, two of the most popular drinks in the country.

The next day, the stock exchange slumped and restaurants began canceling orders for Coke, beer, even ice cream. The banks on the target list suffered bank runs, and other crony firms began to get nervous knowing they would be next. For Filipinos abroad who were monitoring events closely, the apparent success of the boycott campaign was the turning point. As Rene Ciria-Cruz, a San Francisco-based activist recalled, “When the economy experienced the shock wave, we knew Marcos’ days were numbered.”

While the boycott campaign was initially successful, the opposition also was aware of its limited shelf-life. Unless something dramatic took place soon, the people’s enthusiasm for the boycott would dissipate, and Marcos would ride out the instability in his favor. But what could possibly happen short of a violent overthrow?

The answer came from the least expected sector. The military was Marcos’ source of strength, the pillar of his martial law. But by February 1986 the once cohesive military had already fractured and the Reform the Armed Forces Movement (RAM) was ready to make its move.

Next week: RAM and People’s Power

Some portions of this piece are excerpts from “The Fall of the Regime,” Dictatorship and Revolution: Roots of People’s Power (Conspectus Foundation Inc., 1988)