Cathy Sanchez Babao, Grief Whisperer

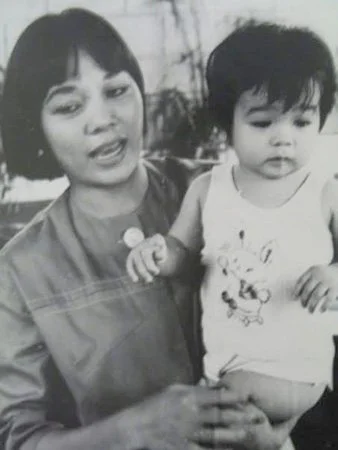

/Cathy with her mother, the veteran actress Caridad Sanchez (Photo Courtesy of Cathy S. Babao)

Her essay, according to Cathy, dredged up emotions that reached back two generations—all the way to World War II. Losing her father at the age of 16, this daddy’s girl grieved and, for years, tried to find the missing piece in understanding him. When her cousin Bernadette googled the name of their Lolo, Cathy’s grandfather, a court drama was revealed with the original transcript of their grandmother’s testimony in the 1945–46 war tribunal. With further research at the University of Texas in Austin, Cathy found the file on her grandfather’s WWII human rights case.

“I never quite knew what to do with it. Was it a short story? A novel? A screenplay? It felt too big, too heavy, too full of memory,” says Cathy.

Living near the American Cemetery and Memorial at Bonifacio Global City in Taguig, Metro Manila, she would hear the carillon bells play hymns every hour on the hour from 7:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. It reminded her that, at age five, her father would always take her there. When he died, she dreamed they were in an all-white room, but she couldn’t remember anything from that dream except the word “McKinley,” which she knew was in Forbes Park or Greenhills.

Caridad Sanshez with Cathy growing up (Photo Courtesy of Cathy S. Babao)

“Fast forward: when I needed to buy a new home, nagpirmahan ng kontrata, sabi ko, anong pangalan ng kalye (at the contract signing, I asked, ‘What’s the name of the street?’). McKinley!” Cathy was astonished by the synchronicity that led her to include aspects of the cemetery and the bells in her essay. Halfway through her writing, however, she almost threw in the towel. Exhausted, she pushed her laptop away and told herself she needed a long break.

“The following morning, while sitting on our balcony,” Cathy continues, “a chubby gray pigeon landed right on the railing and stayed there for about a full minute. In nearly ten years of living in that building, I had never seen a pigeon perch there before. It simply stood still, as if waiting for me to notice. I snapped a photo, and then, mission accomplished, perhaps, it flew away.”

Then she learned something that made her hair stand on end: that pigeons played a crucial role during World War II, carrying messages from the front lines, helping rescue aircrews, and delivering intelligence for resistance fighters when every other communication line had failed.

“In that moment, I knew,” she says. “I felt, deep in my chest, that the Divine was nudging me to continue. After all, this was a story born from a family tragedy during the war—a story that had waited decades for a sliver of redemption.”

A few weeks later, after finishing her draft of The Cemetery Playlist, she looked out the window, and there it was—a full double rainbow, arched right over the very place that formed the backdrop of the essay about her dad and grandfather. She says it felt like a blessing, a gentle whisper from above saying, “Carry on!”

Between Loss and Forever

Cathy Sanchez Babao is no stranger to family tragedies. In May 1998, her four-year-old son, Migi, asked her through sobs before he was wheeled into the operating room, “Will you be with me forever?” Cathy replied yes—she would be with him all the way to forever. That was the last time Cathy would see him awake.

The death of a child goes against the natural order of the universe, where children bury their parents, not the other way around. The immense loss changes the life of the bereaved forever. The heartbreaking journey to understanding its meaning, which is an essential component to healing, can also take a lifetime. For Cathy, she found the need to search for meaning and understand the steps a mother takes as she goes about healing herself while going through the various stages of grief. That search took her 13 years of research in the field of children’s health advocacy, grief education, and counseling, and to write not just about her own grief journey, but also that of over twenty other Filipino mothers. And that, says Cathy, “has all been in response to that promise I made to my son that morning in May,” the beautiful and meaningful outcome of which is the book Between Loss and Forever (Anvil, 2011).

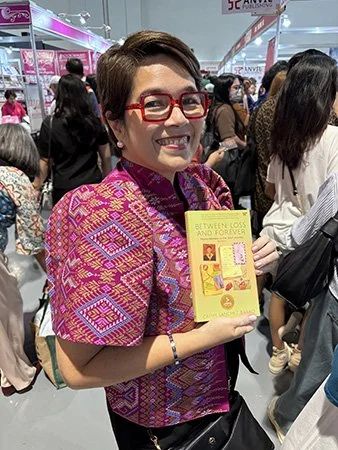

Book launch of Babao’s Between Loss and Forever (Photo Courtesy of Cathy S. Babao)

Within the pages of the book are stories of mothers and their grief journeys at different periods of time. Thelma Arceo lost her eldest son, Ferdie, then 21, to the military during martial law in 1973. Alice Honasan’s youngest son, Mel, died from a brutal and senseless hazing in 1976, while Lissa Ylanan Moran lost her infant daughter a few months after the EDSA Revolution in 1986.

There are also the stories of mothers Raciel Carlos, Jo Ann de Larrazabal, Isabel Valles Lovina, and Mano Morales, whose children died in their prime in car accidents. Baby Tiaoqui and Fe Montano lost their adult children to illness. Beth Burgos Adan, Aleli Villanueva, Monique Papa Eugenio, and Aileen Judan Jiao lost theirs in various unexpected ways, while Vivian de la Peña’s and this author’s children felt that life was too painful and chose to end their suffering.

After more than a decade, Anvil issued a new edition of Between Loss and Forever: Filipino Mothers on the Grief Journey, with updates on some of the mothers from the first edition— “brief glimpses into where they are now, how their grief has shaped them, and what they have learned in the years since.” There are also new voices—Shamaine Centenera Buencamino, who lost her 15-year-old daughter Julia to suicide in 2015, and Lyn Ynchausti-Cruz, whose 37-year-old son passed away from lymphatic cancer in 2018.

The Vietnamese Buddhist monk, peace activist, and prolific author Thich Nhat Hanh wrote: “The best that we can do for those who have died is to live in such a way that they continue, beautifully, in us.” Bereaved mothers, like Cathy, may have found the answer to the question, “How does one make sense of a world shattered to pieces?” through that nugget of wisdom. The book written by Cathy is now serving as a kind of roadmap to others who are new to their grief journey.

Tribute to a Showbiz Mom

Meanwhile, even as her book on mothers on their grief journey is Cathy’s response to her promise to her son that day in May 1998, she recently came out with another book that was written to honor a promise she made to her mother.

Friday’s Child: Tales from a Non-Showbiz Childhood (Buensalido Public Relations Agency, 2025) is a collection of personal essays and stories about growing up with her mother, the esteemed Filipino veteran actress Caridad Sanchez. The book, with its title inspired by the old nursery rhyme where “Friday’s child is loving and giving,” is dedicated to “Mom—who gave me the stories, and the strength to tell them.” And to “Mark—who gave me the quiet courage and loving space to return to where it all began.”

Cathy with mother Caridad Sanchez (Photo Courtesy of Cathy S. Babao)

The book, according to Cathy, is a collection of scribbles of a Friday’s child who is “wildly imaginative, occasionally melodramatic, and prone to scribbling down every childhood mishap as if it were Pulitzer-worthy.” She adds, “Memory, like childhood, is often messy… Some chapters are funny, others are weepy. But all of them are stitched together by a deep sense of wonder for the way a girl becomes who she is—not in one big, sweeping transformation, but through a thousand small, ordinary moments.”

The death of a child goes against the natural order of the universe, where children bury their parents, not the other way around.

On lessons from her mother, Cathy wrote: “She taught me that strength isn’t always loud. Sometimes, it’s the woman calling you from the gate, waiting quietly for the door to open, calling you home.”

And this, too: “Be like the willow. Allow yourself to grieve, to sway with the winds of change. But don’t break. You are built to bend and rise again. Like my mother in her garden, hands in the dirt, hose in one hand, and a heart that refused to give up. And maybe, just maybe, even when we choose to cut things down in our pain, something stronger will grow in its place.”

Cathy has learned her lessons well. Her life has been transformed since she wrote the first edition of her book, Between Loss and Forever. Her children have grown into remarkable adults: Pia, the eldest, Migi’s Ate, is now a psychiatrist; and Iago Leon, who came after Migi, is a writer and playwright who won his Palanca last year for a full-length play, a year ahead of his mother. Cathy’s marriage ended, but life, even with its complexities, presents second chances. Cathy found love again in Mark, whom she married a couple of years back, “a testament to the fact that even after great sorrow, love finds its way back to us.”

Cathy with daughter Pia, now a psychiatrist (Photo courtesy of Cathy S. Babao)

Cathy with son Iago Leon at Arete (Photo courtesy of Cathy S. Babao)

Alma Cruz Miclat is a freelance writer and retired business executive. She is the president of the Maningning Miclat Art Foundation, Inc., and author of the books Soul Searchers and Dreamers: Artists’ Profiles and Soul Searchers and Dreamers, Volume II, and co-author, with Mario I. Miclat, Maningning Miclat, and Banaue Miclat, of Beyond the Great Wall: A Family Journal, a National Book Award winner for biography/autobiography in 2007.