Auschwitz, Anyone?

/Hitler

Soon after Hitler became Germany’s Chancellor in 1933, he built concentration camps to detain his opponents and people he deemed undesirable. The earliest prisoners were German communists and socialists. Later, he also jailed Jehovah’s Witnesses, Jews, Roma, criminals, homosexuals, the homeless, and the mentally ill.

In September 1939, the Nazis invaded and occupied part of Poland, thus starting World War II. As they rounded up more people, they built more concentration camps in the occupied countries.

Seventy kilometers from Krakow, Auschwitz was one of these camps. Originally a prewar military barracks, the buildings were converted into prison quarters. Its first inmates were Polish political prisoners.

The Nazis soon found the need to expand. In the nearby village of Birkenau, they evicted the residents and built a bigger camp with better killing apparatuses. Together, Auschwitz I and Auschwitz II (Birkenau) could hold some 110,000 inmates. There was also Auschwitz III, a collection of sub-camps (like Plaszow) holding prisoners used as slave laborers in factories and farms seized by the Nazis to produce military supplies. To isolate these camps from the general population, the Nazis enclosed them in electrified barbwire fences and used the surrounding structures for their own barracks.

When the Soviet Army approached Auschwitz in January 1945, the Nazis frenziedly killed thousands of inmates, bombed the crematoria, burned what they could, and then marched some 60,000 prisoners westward, intending to use them for further forced labor. The Soviets, finding around 9,000 sick or weak inmates who had been left behind to die, set up hospitals to aid the survivors. Some who had enough strength made their way out of the camp on foot.

Not all of the survivors left the town. Some of them stayed to make sure that the complex was not totally dismantled by the locals for wood. Afraid that Auschwitz would be claimed back by nature and forgotten by history, they became stewards of the site until it eventually took the form it has today: a memorial to the victims and a museum to be shared with all of humanity.

Come along now for a guided tour inside the camps. Picture yourself being shoved into one of the cells by a man you recognize. Wasn’t he the baker in your village? You’ll soon figure out that he is also an inmate but is now working for the Nazi guards.

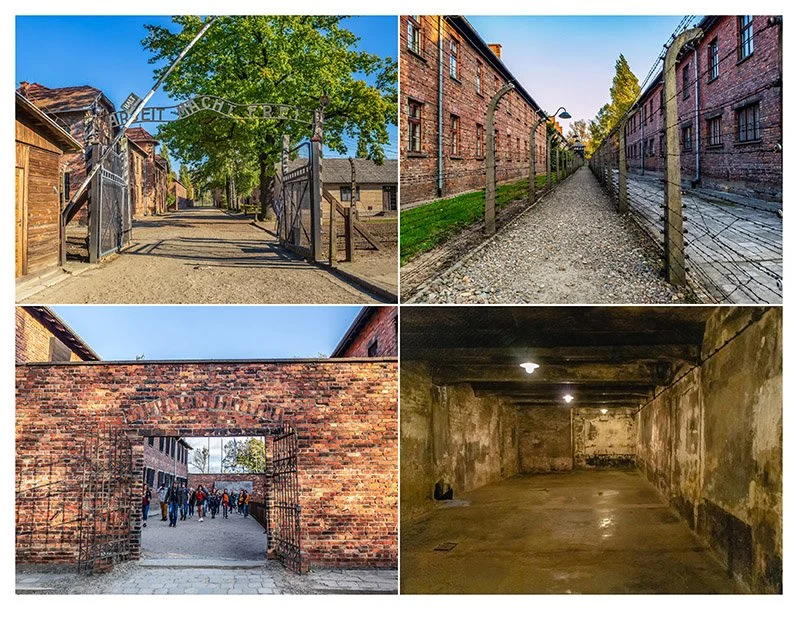

Auschwitz I

Top: The main gate with Arbeit macht frei (Work sets you free) sign; Layers of barbwire enclosing some cell blocks.

Bottom: Gas chamber; Death Wall between Blocks 10 and 11 where about 5,000 resistance prisoners were shot

.(Photos by Odette Foronda, Auschwitz I, 2018)

Top: Confiscated shoes and prosthetics

Middle: Zyklon B canisters and prisoners’ bunks that held two per level

Bottom: Incinerators and toilets

(Photos by Odette Foronda, Auschwitz I, 2018)

First, the Nazis killed prisoners by shooting them. When that became too slow, too stressful for SS guards and policemen, and hard to hide from the public, they loaded prisoners in vans and suffocated them with the carbon monoxide from the vehicles’ exhaust pipes. When that also became too slow, they devised gas chambers using Zyklon B, a cyanide-based pesticide. Even so, after two years, it was no longer viable for the Germans to keep the growing number of Jews in crowded ghettos.

To fix the efficiency problem, top-ranking Nazis met in 1942 at a villa in the Berlin suburb of Wannsee. At that conference, top SS men Heinrich Himmler and Reinhard Heydrich presented the Final Solution to the Jewish Question: a plan to sweep all Jews in Europe and deport them to killing centers. They chose Auschwitz for a major killing center, among five others, all in Poland, citing two reasons for these choices: favorable location transport-wise, and the ease with which the area can be isolated and camouflaged. The plan was ready to go; they simply needed to ensure the cooperation of various government departments to implement it. Which they got.

And so, Jews from all over Europe were rounded up from previously established ghettos and packed in trains bound for Poland. Told that they would be “resettled in the east” where they could work, they packed their valuables and got their families dressed for the journey.

Some were put on passenger trains, but most were tightly packed in sealed freight or cattle cars without food, little light, and ventilation, and with a bucket for a toilet. It was either sizzling hot or freezing cold. The journey took days, and those who tried to escape were shot on the spot. Many died on the way.

At first, the Nazis used existing railways next to Auschwitz I and Birkenau. With the increasing arrivals, a third ramp was built inside Birkenau. At this ramp, all the arriving passengers were immediately subjected to the selection process, which went this way:

Once passengers disembarked, their luggage was confiscated. They were sorted into two columns: one for women and children, another for men and older boys. The children and the elderly were sent to die. A camp doctor briefly looked at the men and older boys. Those he deemed fit for work were sent to barracks; the rest to the gas chambers.

About 80 percent of arrivals were marched directly to the gas chambers several hundred meters from the ramp. They were told that they were being taken to their barracks but first they needed a shower. After they undressed, however, they were herded to the gas chambers.

After the screaming stopped, the bodies were dragged out, their hair cut, their gold teeth pulled, the jewelry removed. The corpses were burned in the crematoria or outdoor pyres. Unburned bones were pounded and mixed with the ashes which were then scattered in nearby rivers or used as fertilizer or landfill.

The remaining 20 percent of arrivals were divested of their clothes and belongings, their hair cut. They were sent to a shower and then given uniforms or clothes and shoes from the confiscated things. A prisoner number was tattooed on their arms and then they were sent to their cells. They’d be worked to exhaustion, at which time they would also be gassed.

The confiscated gold was melted and sent to a German bank. The hair was used to make textiles for army blankets and other supplies. Of the other items, the best was sent to Germany, and the rest were used in the camps or traded in the black market.

Birkenau

Top: At Birkenau, if you got off a train and stood on the platform, you’d be midway along the width of the camp. This view faces Birkenau’s main gate. If you turned around, you’d see the tracks running to the edge of the camp where the crematoria are. The main gate had no Arbeit Macht Frei sign because it was a death camp, not a forced-labor one.

Bottom: A cattle car. Because the barracks were hastily built, many of them are in ruins. On the right are ruins of a gas chamber and crematorium.

(Photos by Odette Foronda, 2018)

Top left: For me, this pond where victims’ ashes were dumped is the most sobering spot in Birkenau.

Bottom: The International Monument to the Victims of Fascism sits close to where the gas chambers and crematoria were. Plaques carry the same inscription in 23 languages. The English one (above) reads: For ever let this place be a cry of despair and a warning to humanity, where the Nazis murdered about one and a half million men, women, and children, mainly Jews from various countries of Europe. -- Auschwitz-Birkenau, 1940-1945

(Photos by Odette Foronda, Birkenau, 2018)

Are you furious enough yet? Heartbroken? I’m both, but I’m also worried by what some wise man once said: The only thing we learn from history is that we learn nothing from history.

Krakow

We need a breather now, don’t we? Let’s go see Wieliczka Salt Mine, a major source of Medieval Poland’s wealth for several centuries. Just inhaling the air inside will be good for our lungs. Later, we’ll check out Krakow’s pretty Old Town, which survived World War II intact.

Krakow derives its name from Krakus, an ancient tribal leader who erected a fortified settlement on a hill called Wawel along the Vistula River. Shortly after 966 when Count Mieszko converted to Christianity, Krakow was made the capital of Poland. It was sacked by Mongols in 1241 but was later rebuilt. The oldest of its many churches is from the 11th century.

Wieliczka, Rynek Glowny

Top left: Saint Kinga’s Chapel, the grandest of four chapels carved by miners entirely out of salt inside Wieliczka Salt Mine. The Germans used the mine as an armament factory during World War II.

Top right: 13th century Cloth Hall, Krakow’s center of trade for many centuries

Bottom: The size of two city blocks, Rynek Glowny is one of the largest Medieval squares in the world. St. Mary’s Basilica is on the left; St. Adalbert Church on the right.

(Photos by Odette Foronda, 2018)

Wawel Castle, Barbican

Top: Wawel Castle by the Vistula River was the royal residence for almost six centuries. During the Nazi occupation, Hans Frank lived here like a king.

Bottom, from right: St. Florian’s Gate; 15th century Barbican; Wawel Cathedral.

(Photos by Odette Foronda, 2018)

In the 14th century, King Kazimierz the Great established a Jewish quarter (named Kazimierz), which later became part of Krakow. Because he welcomed Jews who were expelled or fleeing from other parts of Europe, synagogues were built there, and a big Jewish community flourished.

Sorry now, I know I said we’re taking a breather here in Krakow, but while walking around, we can’t help but go back to the time of the Nazis.

When the Nazis arrived in 1939, they closed the synagogues, rounded up the Jews, and herded them across the Vistula River to the Podgorze district, which they walled off and transformed into the Krakow Ghetto. Plac Zgody, the ghetto’s central area, was where the Nazis would gather the Jews to decide on who would be sent to Auschwitz (to die) or to Plaszow (to work). The ghetto was in use from March 1941 to March 1943 when it was ordered liquidated, i.e., closed. After the war, Plac Zgody was renamed Ghetto Heroes Square. In 2005, a monument was installed to honor all the Jews whose fates were sealed here. It consists of giant chairs that symbolize the personal belongings they left behind before they were transported to their deaths.

Kazimierz & Podgorze

Top row, from left (Kazimierz): The 13th century Old Synagogue, now the Jewish Museum; Tempel Synagogue; a Kazimierz street

Bottom: Ghetto Heroes Square (Podgorze)

(Photos by Odette Foronda, 2018)

Let me guess what you’re thinking: Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List. How many times have you seen it?

Although the actual Jewish Ghetto was in Podgorze, Spielberg shot most of the movie’s ghetto scenes in Kazimierz because at the time of filming, there were more spots in Kazimierz that still had the same buildings and streets as they had during the war.

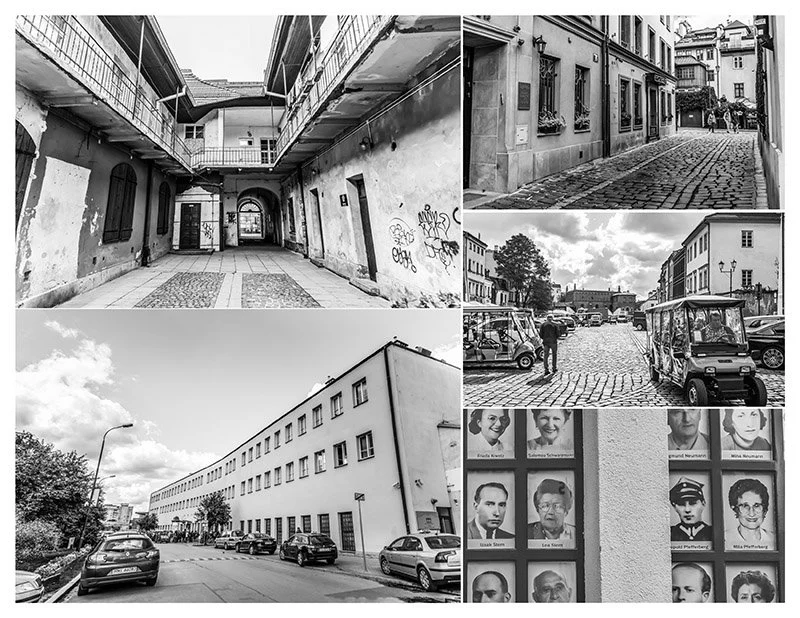

Schindler’s List

Top left: Some Schindler’s List ghetto liquidation scenes were shot in this apartment building on Jozefa 12. In the movie, this building is in the ghetto. SS guards enter each door, hurl the Jews’ belongings down to the courtyard. A family hurries to swallow diamonds. Gunshots, screams, bedlam.

Bottom left: Schindler’s Factory in Podgorze, now a museum.

Top right: Ciemna street is where Poldek (Jonathan Sagall) emerges from the sewer and finds suitcases strewn on the street. He starts clearing the street of the bags and salutes the approaching guards. Plaszow commandant Amon Göth (Ralph Fiennes) disdainfully laughs but decides to spare Poldek and walks away.

Middle right: This street by the Old Synagogue was used for scenes that actually happened at PlacZgody.

Bottom right: Photos of Schindler’s Jews are displayed at the Schindler Factory Museum. The middle row shows Izaak Stern (Ben Kingsley), Poldek Pfefferberg, and his wife Mila.

(Photos by Odette Foronda, 2018)

When the Pope Was Polish

Want to go for a spin in a Communist-era Trabant? Let’s hop in one to see Nowa Huta.

After World War II, Poland became part of the Eastern Bloc under Stalin’s rule. On the outskirts of Krakow, the Communists built Nowa Huta, meant to be the ideal socialist city. Its steel mill became the biggest in Poland. Next to it were concrete blocks of apartments that housed 250,000 residents.

The suburb had restaurants, stores, parks, playgrounds. But no church. The Catholic residents demanded permission to build one. No go. Karol Wojtyla, then Archbishop of Krakow, helped the residents protest and lobby. They erected a wooden cross on an open space where Wojtyla would celebrate mass. Each time the cross was taken down, the Catholics would replace it even if it meant violence from the riot police.

In 1967, they obtained permission to build a church but were not given the funds, so they brought their own materials (like river stones), collected contributions overseas, and contributed their labor to build Arka Pana (The Lord’s Ark). The church that resembles a boat was consecrated by Archbishop Wojtyla in 1977, the year before he became Pope John Paul II.

In the 1980s, anti-Communist fever spread across Eastern Bloc countries, fueled by rising cost of living and repressive laws. Poland’s leading figure was Lech Walesa, the force behind Solidarity. After several protests, the Communist government allowed the workers to organize a trade union. Over 20 trade unions merged to form Solidarity, a movement which, by 1981, had ten million members nationwide.

After seeing the movement spread like wildfire, the Kremlin declared martial law, abolished Solidarity, and jailed Walesa and his companions. Too late, honey. The organization went underground. Churches, Arka Pana among them, hosted meetings and lectures and helped produce illegal publications. Priests were killed or jailed, but the movement forged on. Through it all, John Paul II encouraged Walesa and his men to be firm but peaceful in demanding for change.

After waves of protests, Solidarity became legal again. The Communists under Mikhail Gorbachev agreed to share political power, and in June 1989, elections were held, resulting in sweeping wins for Solidarity. Soon after, the other Eastern Bloc countries followed suit, the Berlin Wall fell, and Communism collapsed in Europe.

Nowa Huta

Top: Nowa Huta’s central square and residential blocks

Bottom: Arka Pana Church; my guide, Karolina, poses by her rickety Trabant in front of the steel mill.

(Photos by Odette Foronda, 2018)

We’ve half a day left. Are you up for some soul-soothing?

Kalwaria Zebrzydowska was built by a Polish nobleman as an alternate pilgrimage site to Jerusalem when it was under Ottoman rule. After Karol’s mother died when he was eight, his father took him and his brother to Kalwaria Zebrzydowska. Before an image of the Virgin Mary, the grieving dad told his young sons that she was now their mother. From that point on, Karol regarded the Blessed Mother as his own mom and remained devoted to her for life.

Come along now for a guided tour inside the camps. Picture yourself being shoved into one of the cells by a man you recognize.

Faustina Kowalska was a Polish nun who claimed that Jesus appeared to her several times, giving instructions on the veneration of what He called the Divine Mercy. Predicting a terrible war, she asked the nuns to pray for Poland. She died in Krakow in 1938, the year before Germany invaded her country. When Pope John Paul II canonized her in 2000, he also declared the Sunday following Easter as Divine Mercy Sunday. The Divine Mercy Sanctuary is in the compound where St. Faustina had lived and worshipped just outside Krakow.

Wadowice is where Karol Wojtyla was born in 1920. His family lived in a flat next door to the church, where he was baptized and served as an altar boy. To avoid deportation during the war, he worked in a quarry and a chemical plant, which supplied the Nazis with their needs. After his father died in 1941, Karol started attending classes in a clandestine seminary in Krakow. He was ordained into the priesthood in 1946 when Poland was under Soviet rule. He became Pope John Paul II in 1978.

He is regarded as one of the prime movers toward the peaceful fall of Communism in Eastern Europe. Pope Francis canonized in him in 2014 on Divine Mercy Sunday.

Mini Pilgrimage

Top: Wadowice’s Market Square. In the orange building next to the basilica was the John Paul II family home, now a museum.

Bottom: Kalwaria Zebrzydowska Basilica; Divine Mercy Basilica

(Photos by Odette Foronda, 2018)

So! Was the wise man right about us not learning anything from history?

In his bunker as the Allies closed in on Berlin, Hitler married his mistress before they both killed themselves with cyanide and bullets. The next day in the same bunker, his chief propagandist Goebbels and his wife poisoned their six children before killing themselves. Himmler ate cyanide. Heydrich was assassinated. Frank, Göth, and Auschwitz commandant Höss were hanged.

All alone in his room, Stalin had a stroke and marinated in his pee for three days before a brain hemorrhage dealt him the coup de grâce.

This article consists of excerpts from Odette Foronda’s book Places I Remember: Poland published in 2024 by Reischling Press, Tukwila, WA. Places I Remember: Poland by Odette Foronda | Blurb Books

Odette Foronda is a mother of four and grandma of four. Based in Toronto and now retired from years of working in the numbers field, she’ll travel as far as her Ilocano purse will allow. She publishes books of her travel photos and stories (https://www.blurb.com/user/odettef).

More articles from Odette Foronda