‘A Time to Rise’: Filipino American Memoirs of Revolution

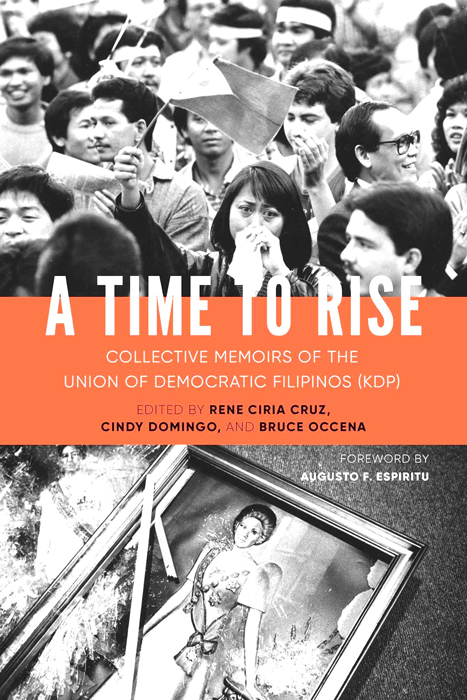

/"A Time to Rise"

Ciria Cruz writes in the Introduction that, for the baby boom generation, it was a "time to rise," and rise they did. The members of the "KDP" -- the Katipunan ng Mga Democratikong Pilipino ("Union of Democratic Filipinos") -- came together out of a common feeling of necessity to stop the Marcos dictatorship government in the Philippines and to bring about social change in America. But reading their stories in this "collective memoirs" reveals that there was much more to their political organization than merely meeting an appointment with history. There were also lots of tears, pain, suffering, soul searching, confusion and deep disappointment amidst the joy, elation and euphoria of the possibility of bringing about a socialist revolution. Somewhere along the way, they also found meaning, purpose, redemption and hope.

Many of the stories in this collection are of painful memories and deep ambivalence about the years that transpired working for the KDP organization and for the Movement. But, as Edwin Batongbacal writes in what was chosen as the final essay in the collection, he has "no regrets." Or at least that is where he wants to be, where he would like to remember his years with the KDP.

The KDP was born out of political necessity. On September 21st, 1972, President Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law in the Philippines, and the political ramifications of martial law reverberated across thousands of miles of ocean and was felt immediately in Filipino American communities in the United States. Filipino Americans felt the need to fight against the injustice of Marcos, an authoritarian dictator, and his martial law government that suppressed democracy and civil liberties.

Marcos' dictatorship was also supported by the U.S. government. Thus, only two days later, on September 23rd, a national coalition of Filipino activists in the United States was formed to fight martial law: the National Committee for the Restoration of Civil Liberties in the Philippines (NCRCLP). The NCRCLP, however, was a mixed coalition of anti-Marcos activists. Some NCRCLP elements were Filipinos from the political elite and were opposed to martial law mainly so that democracy could be restored, and they could return home to their social rung in Philippine society. Other members were not only opposed to Marcos's martial law government, but they also wanted more fundamental political change in Philippine society. These more radical, leftist members did not want a resumption of the traditional ways of politics where the rich, political elites would continue to run the Philippines and maintain the status quo of class inequality.

Many of the NCRCLP radicals were from the Kalayaan Collective in San Francisco, who advocated an "anti-imperialist perspective" and even openly supported a socialist-oriented armed struggle in the Philippines. Hence, in July 1973, Kalayaan radicals and student activists gathered in Santa Cruz, California, and officially formed the KDP, Katipunan ng Mga Demokratikong Pilipino ("Union of Democratic Filipinos"), an openly Marxist organization with a "dual-line" program of 1) supporting democracy in the Philippines by bringing an end to Marcos's martial law government, and 2) promoting socialism in the United States--implicit in this dual goal was also supporting a socialist movement in the Philippines. Many of the KDP founding members had attended an earlier gathering of Filipino activists called the Young People's "Far West Convention," the first one in 1971 in Seattle and the second in 1972 in Stockton. After the third Far West Convention in 1973 in San Jose, the KDP published Ang Katipunan, which provided the means of advocating the organization's political views, as well as a recruiting tool.

A Time to Rise contains more than 40 essays that comprise the "collective memoirs" of former KDP members. It is also a book edited by former KDP members. The University of Washington Press deserves much praise for publishing this collection. Some of the memoirs are very descriptive and provide an insider's view of the KDP as a political organization.

For example, Dale Borgeson, one of the founding members of the KDP, is not even Filipino. He is of Swedish descent, a U.S. Army veteran who got out of the military by becoming a conscientious objector. Borgeson joined the KDP by "accident." He was arrested in the Philippines while engaging in anti-war activities, and one of his colleagues was Melinda Paras, a Filipino American and also a future KDP member. Borgeson would eventually return to the U.S. and was assigned to start a KDP chapter in Seattle. In "The Birth of a KDP Chapter," Borgeson provides valuable information on how the KDP conducted community outreach and organizing, as well as the challenges it faced from established Filipino Americans who did not want to upset the social order by challenging the Marcos government. These leaders’ main goal was to unify the Filipino American community. There should be no discussion of martial law, they argued, since it was a controversial and possibly disruptive topic. Some Filipinos also feared that protesting against Marcos would endanger their families in the homeland. But an even deeper issue was that, sometimes, support or opposition to Marcos fell heavily along regional lines. Marcos was Ilocano, and many people from the Ilocos region felt proud that an Ilocano finally became president; thus, they were reluctant to join the anti-martial law movement. Borgeson's essay sheds important light on how the KDP navigated this complex political terrain; how radicals such as Philip Vera Cruz, Carlos Bulosan, Chris Mensalves provided inspiration to a nascent political organization and the uphill battles the KDP had to fight in dealing with established Filipino American community leaders and organizations who were not supportive of their anti-martial law organizing.

Workers’ Rights

The impact of the KDP was felt most significantly in organizing for workers' rights. Ester Hipol Simpson's essay, "Defending Nurses--I'd Do It Again," shows one of the major successes of the KDP. She attended the prestigious St. Paul College in Manila and graduated with a nursing degree. After completing her master’s in nursing from the University of the Philippines, Simpson eventually immigrated to America to fulfill her dream of pursing a nursing career. While working as a nurse in Chicago, she became involved with NCRCLP, the anti-martial law organization, through which she met KDP members. She also learned about the exploitation and oppression of many Filipino immigrant nurses who were receiving lower wages and stuck at lower tier jobs in nursing. Some nurses were even in danger of deportation for failing to pass their nursing licensing exams. By this time, Simpson had become a KDP member and was in charge of the KDP campaign to protect the rights of Filipino nurses. The success of KDP's campaign led to major changes that allowed Filipino nurses to have a higher chance of passing their nursing licensing exams and even caused Immigration and Naturalization Service officials to change their policies. "These victories," Simpson writes, "especially those won from the much-feared INS, sent shock waves through the Filipino community."

The high point of the KDP's civil rights work in the nursing community came in 1977, when it successfully defended two Filipina nurses, Filipina Narciso and Leonora Perez. These Filipino nurses were "accused of murdering thirty-five patients at a Veterans Affairs hospital in Ann Arbor, Michigan." A broad-based national campaign led by the KDP widely amplified the nurses’ proofs of innocence and helped lead to their acquittal. It also exposed the VA hospital’s attempt at blaming scapegoats for its incompetent management. Simpson writes, "This is the first time in Filipino American history that the community held an orchestrated nationwide protest against a domestic injustice."

In San Francisco, the KDP also played a crucial leadership role in protesting against domestic injustice, this time involving the eviction of elderly Filipino American residents at the International Hotel ("I-Hotel") along Kearny Street and Jackson, just outside of Chinatown and at the edge of the Financial District. KDP members Emil de Guzman, Estella Habal and Jeanette Gandionco Lazam were centrally involved in the struggle to stop the I-Hotel evictions.

Supporters of I-Hotel rally against the eviction of its residents (Photo by Chris Hule)

In 1975, in her essay, "Is This What You Call Democracy?" Lazam writes a powerful story about her work to save the I-Hotel. At that time, she was a student at City College of San Francisco, so she decided to live as a resident in the I-Hotel. The residents of the I-Hotel received eviction notices in 1974, and Filipinos, Asians, blacks and other activists from all ethnicities in San Francisco came to the Hotel's defense, and eviction was avoided until 1977. The Court ordered the City to enforce the eviction, so at 3 a.m. on August 4th, Sheriff Richard Hongisto and heavily armed riot-geared police came to forcibly evict the residents of the I-Hotel. Lazam's essay provides an insider's account on how activists fought valiantly to defend the Filipino elderly residents of the I-Hotel, and how they were overwhelmed by police units who broke down the doors and windows to forcibly remove its residents. Her task was to defend Wahat Tampao, the 75-year-old elderly president of the I-Hotel's Tenants Association. She was there at his side when the police used sledge hammers to break into his room and force them out. They surrendered to the police and were escorted out of the Hotel. Outside on the streets, feeling "like we had lost," Lazam recalls how Wahat "fell to the pavement on his knees and cried. I cried with him and for him."

Justice for Domingo and Viernes

However, the most significant involvement of the KDP was in the fight to bring justice in the case of KDP union organizers Silme Domingo and Gene Viernes. Domingo and Viernes were KDP members who joined the Alaska Cannery Workers Union (ILWU, Local 37) and were organizing within the Union to institute reforms, job fairness and to remove the corrupt union leadership who were involved in gambling, bribery and other illegal activities. Several authors wrote stories about their memories of Domingo and Viernes and how they dealt with the 1981 events.

A newsletter from the Committee for Justice for Silme Domingo and Gene Viernes (Source: University of Washington)

In "Initiation from Hell," Emily Van Bronkhorst shares her firsthand experience working at the Egegik fish cannery in Alaska, of how a KDP member worked side-by-side with other cannery workers. Van Bronkhorst is white, and she explains the race privilege that white workers enjoyed, compared with Filipinos who had the less desirable jobs of butchering and slimming the fish. She describes how corrupt Filipino union leaders and their "gangster" thugs worked to intimidate cannery workers. She was present in Seattle when union members voted Domingo and Viernes into key leadership positions of the Alaska cannery union.

In "A Day I'll Live With for the Rest of my Life," David Della writes about arriving at the Seattle union hall on the late afternoon of June 1st, 1981 when emergency vehicles were at the murder scene. Della positively identified the body of Viernes and called fellow activist Leni Marin to share the tragic news with other KDP members. Domingo was still alive (barely) and was taken to intensive care at Harborview Hospital. A police officer gave Della a ride to Harborview, and the officer shared that Domingo had identified his shooters. The officer noted that "this was a gangland slaying done by a group called the Tulisan (Bandits), a gang tied to gambling in Chinatown." Domingo would live for another 24 hours and identified the shooters as gang members Jimmy Ramil and Pompeyo "Ben" Guloy Jr.

Terry Mast, wife of Silme Domingo, was also at Harborview on that fateful day in June 1981. In her essay, "We had Already Lost Too Much to Turn Back," she recalls how a month earlier she met Ramil in Alaska as he was meeting with union president Tony Baruso, whom the KDP would learn later was responsible for planning the murders. Mast writes, "To this day, it gives me the creeps to even think that I might have been right there, in the next room, the day the contract on Silme and Gene was sealed."

The 1981 killings put Cindy Domingo, Silme's 27-year-old younger sister, into the forefront of the KDP's campaign to bring justice for Domingo and Viernes. In a "Long Road to Justice," Cindy shares her difficult journey and sacrifices in doing the investigative work and organizing a local and then a national campaign to bring justice for Domingo and Viernes. "All the KDP and Local 37 activists," Cindy writes, "were thrust into leadership positions after June 1." Eventually, that coalition of KDP members and their supporters formed the Committee for Justice for Domingo and Vienes (CJDV). A few months later, in September 1981, Ramil and Guloy were convicted of murder and sentenced to life imprisonment without a possibility of parole. However, CJDV believed that the murders were ordered by people higher up in the union leadership and that the Marcos government was also ultimately involved.

Despite the murder convictions of the shooters, the CJDV continued is hard work and campaign for justice. CJDV lawyer Jim Douglas was not a member of the KDP, but his story is included in the anthology, and he writes about the years of investigative work (including the hiring of a "cloak-and-dagger" investigator) and the long legal struggle that led to the trial and conviction of Tulisan gangleader Tony Dictado and later union president Tony Baruso, a supporter and former townmate of Ferdinand Marcos. The KDP/CJDV provided evidence that Dictado hired the Tulisan gang members to carry out the murders. In 1982, Dictado was brought to trial, convicted of murder, and he was also sentenced to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole. This left union president Tony Baruso, whom CJDV believed was in charge of carrying out the overall planning for the murders.

Prior to Baruso's criminal trial, Douglas explained how a civil suit against Marcos was eventually allowed to proceed, aided in part by the overthrow of the Marcos government during the 1986 People's Power Revolution and Cory Aquino's rise to the presidency. By this time, Marcos was in exile living in Hawaii, and Douglas was able to interview Marcos and "take his deposition under oath." The civil lawsuit would eventually come to trial in 1989, and by this time CJDV had a clearer picture of how Domingo and Viernes were murdered. Although they did not find the "smoking gun" that they had hoped for, when the court allowed the CJDV to investigate Marcos and his legal papers--Marcos made the mistake of bringing legal documents when he fled to Hawaii--they discovered that a Filipino physician in San Francisco close to the Marcoses had paid $15,000 from a Marcos slush fund for "special security projects." A subpoena of Baruso's travel records revealed that he was in San Francisco two weeks before the murder and that a $10,000-dollar deposit was made in his bank account. This deposit was consistent with court information from the previous trials that each of the Tulisan gang members was paid $5,000 to execute Domino and Viernes. At the court trial, Douglas and the CJDV team was shocked that Marcos and Baruso's legal team gave few objections and almost no defense of their clients. When Judge Barbara Rothstein issued her court decision, the Committee for Justice for Domingo and Vienes won the federal civil suit and was awarded $8.3 million in damages, in addition to a prior jury award of $15 million. Thus, Douglas concluded, "We had convinced not only a jury but also a presiding judge of the federal court for the western district of Washington" that the Marcos government was involved in the KDP murders.

Given the new evidence discovered in the civil lawsuit, the Seattle prosecution's office brought criminal charges against Baruso, and in 1990 he was convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole. After nearly ten years of legal struggles to bring about justice for Domingo and Viernes, Jim Douglas and Cindy Domingo both ended their essays in a light-hearted manner, which is a good reminder that some of the essays in the collection of memoirs were quite funny and brought a much needed light-heartedness. They both joked about who would play them in a possible Hollywood movie of the ordeal.

“The members of the “KDP” — the Katipunan ng Mga Demokratikong Pilipino (“Union of Democratic Filipinos”) — came together out of a common feeling of necessity to stop the Marcos dictatorship in the Philippines and to bring about social change in America.”

Lighthearted Stories

Lightheartedness characterizes Sorcy Apostol's recollection when she went to protest Marcos' arrival in Hawaii in 1979. Other KDP members Rene Ciria Cruz, Jeanette Gandionco Lazam, and Apostol's husband Bo (who also has a story in the book) and their infant daughter were all sent to Hawaii. The KDP organized a covert protest at the Honolulu airport. Sorcy was posing as a pro-Marcos supporter, but she was actually hiding an anti-Marcos banner. I laughed and cried at reading her account of being scared ("Bo would be a widow again") but determined as she snuck her anti-Marcos banner in her bag through airport security, pretended to be one of the multitude of pro-Marcos supporters and then was gripped with fear again as she thought about the pro-Marcos supporters who "might try to lynch me once I started to protest." Apostol regained her courage when she saw another covert KDP member in the crowd, activist/photographer Rick Rocamora. When she finally unfurled her anti-Marcos banner and she shouted, "Marcos, Hitler, dictator, tuta! (puppet)," Marcos mistook Apostol for an American-born Filipino who could not speak the Filipino national language. Apostol, who is a Tagalog language instructor at Sacramento City College and the University of California at Davis, shouted back, "Putang ina mo! Sinong may sabi sa iyo? Sino ang Kano? Pilipino ako!" (You son of a bitch! Who told you that? Who is the American? I'm Filipino!"). Of course, the news media and TV cameras caught all of this and broadcasted the scene with the appropriate curse words bleeped out! Apostol, however, was beaming in the knowledge that she knew that the Filipino community saw and heard her on TV hurl expletives at Marcos.

The lighthearted stories bring a much-needed break in the memoirs, and I enjoyed reading those snippets. Christina Araneta's pen name of "Ma. Flor Sepulveda" had an FBI agent asking another KDP member, "Who is this Ma. Flor Sepulveda?" Similarly with Velma Veloria's story when she visited her hometown of Bani, Pangasinan and had her first encounter with activists who kept talking about "this thing called U.S. imperialism." (It brings back memories of my first visit to the Philippines as a young teen and having my college-age cousins constantly railing about "U.S. imperialism," and I had no clue to what he seemed to be accusing me about.)

I also thoroughly enjoyed Therese R. Rodriguez's "To Teach the Masses a Love for Bach, Chopin and Beethoven," and I am reminded of Emma Goldman’s statement that in the revolution, we have to be able to sing and dance; otherwise, she would not want to be a part of it. There are other humorous and lighthearted moments shared in this collection, too many to adequately discuss here. Those moments are gems because the gripping stories of sacrifice, pain and hardship by a dedicated group of activists are what make this collection so special.

I am particularly taken by Gil Mangaoang's poignant but funny story of coming out as a gay man in the KDP, and the loss of his partner Michael Jerry Krause. Sometimes social movements require so much time and sacrifice from its members, and one's personal life is often forgotten and neglected. Mangaoang touches on this and his eventual disappointment when one of the key KDP leaders who served as his mentor "succumbed to drug addiction." In the end, Mangaoang shares his ambivalence and disappointment with a revolutionary movement in which he and others had invested so much of their time and life: "I felt somehow betrayed by the movement--I had devoted a good portion of my early adult years working for revolutionary change. I so much wanted the revolution to happen. But it was not to be." In one of the concluding essays of A Time to Rise, Mangaoang finds himself walking on the beach in Waikiki reflecting on his life and times with the KDP.

One of most powerful stories in A Time to Rise was provided by Estella Habal, whose writings in this collection I had to read several times for their gripping honesty. Habal's work summarizes for me--an outsider to the KDP organization, but a person who has many friends who are former KDP members and a university professor who teaches Filipino American history--what the history of the KDP was about. Although it lasted only 13 years, the KDP was one of the most powerful and significant organizations in Filipino American history. One cannot discuss Seattle and Alaska union reforms without examining the impact that Domingo and Viernes and other KDP members had on the union. The KDP's contribution to the Narciso/Perez nurses case was very important to their freedom, and similarly, KDP members were in the forefront of the struggle to stop the eviction of elderly Filipinos from the International Hotel. But in the end the organization did not last and had to formally disband in 1986, the reasons for which Ciria Cruz provides in his Introduction essay. Habal's testimonies give a hint at the sacrifices and, in the end, personal toll that the KDP and the Movement took on many of its members. I found her frank reflections very powerful and deeply human, a theme that is also echoed by other former KDP members in their writings. Habal went on to earn a Ph.D. and become a successful university professor, but she still writes that "I have not stopped dreaming...I keep dreaming. I keep struggling." Or as Gil Mangaoang puts it: "Breathe."

Missing in this collection of KDP memoirs are the voices of some key individuals, for example, Bruce Occena, Emil de Guzman and Rodel Rodis to mention just a few. I would also have liked to have heard more about the KDP's connection with leftist organizations in the Philippines, although two memoirs dealt with Philippine revolutionary organizations. Augusto Espiritu's excellent Foreword also covered the rise of the Communist movement in the Philippines and how the KDP arose out of this larger context.

I recommend this book highly for anyone who is interested in the political and labor union history of Filipino Americans. But I also recommend it for people who want to have an insider's view of how members of one of the most important and disciplined revolutionary organizations of the ‘70s and ‘80s felt after dedicating a large part of their lives to "a dream," to borrow Habal's words, of their feelings and reflections several years later when that dream to which they dedicated so much of their young lives is no longer there. In this light, the collective memoirs of the KDP have much to teach us, and we also have much to learn from these activists’ experience and stories.

James Sobredo is an associate professor of Ethnic Studies at Sacramento State University.