A Meeting Of Giants: Jose Garcia Villa And Nick Joaquin

/Jose Garcia Villa and Nick Joaquin

Proof of this is a signed poem that I still own and have had framed, dated February 10, 1997, the day Villa was interred in New York. It goes like this:

A Funereal Effort to Find True Rhymes for Doveglion

Oh, if only we had a hundred Doveglions

Our scions would be top in NIChood,

Or Neo-Ilustrado Culture—meaning the science

Of what we call the true, the beautiful, the good.

And the hundred tongues would have our tongues all loud in defiance

Of whatever would fasten poetry in irons.

But alas in a youth of meanings misunderstood

We had only one such tongue and it was Doveglion’s;

But one voice onward honed, which is Doveglion’s.

Sgd. Nick Joaquin

This is arguably Joaquin’s poetic elegy to his contemporary, who lived from August 5, 1908 to February 7, 1997.

Earlier, Joaquin had written a summary of Villa’s life and accomplishments, “Viva Villa,” excerpted in the Evening Paper as part of its memorial to the renowned author on his passing. Twenty-six years from that day, it is interesting to note how both writers, Villa and Joaquin, had found their respective voices in the new tongue of English to emerge as its masters in their country. The previous generation had, of course written, in Spanish.

Joaquin recounts of how Villa’s father, Colonel Simeon Villa, had been President Emilio Aguinaldo’s personal physician in the long trek from Malolos to Palanan, when he was finally and treacherously captured by the American invaders.

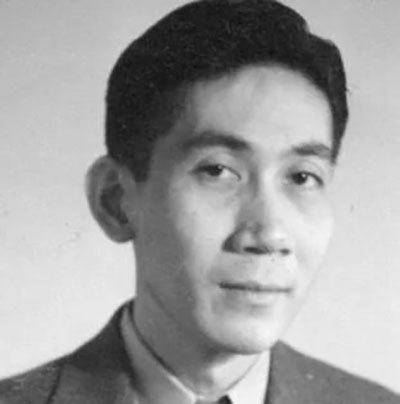

Nick Joaquin

Villa’s family had belonged to the elite of Ermita before the war. He himself had gone to the University of the Philippines and begun his literary career before being expelled for so-called “scandalous” poems published in local journals and the campus newspaper. His Man Songs had lines like these:

The coconuts have ripened,

They are like nipples to the tree,

(A woman has only two nipples.

There are many woman-lives

In a coconut tree.)

I shall kiss a coconut

Because it is the

Nipple of a woman.

For such poems, Villa received a P1,000 prize from the Philippines Free Press, money he used in 1929 to leave for America.

He continued his studies at the University of New Mexico, edited an avantgarde magazine called Clay and published his first book of poetry, Footnote to Youth, which was his adieu to prose. He was married to a “no good” woman with whom he had a child, Robert. When she disappeared and the money ran out, he washed dishes to support himself. His family finally sent him funds to buy a return ticket, which he did in 1939.

There was to be no reconciliation with his father, and he stayed mostly with friends like Manuel and Lyd Arguilla, who lived close by in Ermita. He had expected to receive his inheritance had his father consented to sell the family property, but the latter had refused. Said Don Simeon: “What is the matter with that son of mine? He is very strange. He does not want to live here. He wants to live in America. Why is he an American? He wants me to sell our property. I cannot do that. I must think of my other children. Why doesn’t he settle down here and administer the property?”

After two months in Manila, Villa returned to the United States on a ticket purchased by his friends, but not till he made a return trip from Hong Kong just to say goodbye to his mother and sisters (but not to his father). Father and son were never to see each other again, and Don Simeon Villa perished in the so-called Liberation of Manila in 1945.

In New York, 1942 was a year of triumph for Villa; he published his book, Have Come, Am Here. Dame Marian Moore said that he had written some of the best poems in the English language. Among his awards were those given by the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the Guggenheim and the Bollingen. He was to marry again, this time to an Irish-Italian girl named Rosemary, with whom he had two sons before getting divorced after five years of separation.

Jose Garcia Villa

In 1959, Far Eastern University on the initiative of Dean of Arts Alejandro R. Roces invited Villa to accept an honorary doctorate in literature at its commencement exercises. His homecoming was a triumph after two decades of absence. The following year, Villa had indicated his desire to Dean Roces to teach a year at FEU, a job which the latter was able to secure for him.

His teaching stint at the FEU was nothing short of astounding and unconventional. Joaquin recounts:

When he faced his first class, he announced: “I will not only teach you how to write poetry but also how to make love, because I know more about love than about poetry.”….. Inside and outside the classroom, Villa is a spur, a goad, a catalyst, a “corrupter” and one of the best entertainers off stage. He shakes people out of their conformism, He cuts his own hair, still speaks Tagalog fluently, adores European movies. He considers ballet, opera and the theater “pseudo-culture.”

He thinks only two Filipinos can speak English: Raul Manglapus and Leon Maria Guerrero.

This author’s own grandmother, Mrs. Esther Tempongko-Alcantara, was an English professor in FEU at that time and was fortunate to have participated in Villa’s classes. She remembered him as being professional; he was punctilious both in his preparation and notes, alongside the spice of his wit and side remarks.

Villa grandly announced at the time that he had given up writing poetry since he was now only interested in living and love. This author remembers meeting him in the elevator at the Philippine Center in New York around 1990. He was still lionized by aspiring poets and writers who worshipped at his feet in his Greenwich Village apartment, where he critiqued their work (of one poet in Manila, he had said, “That’s not poetry; it’s diarrhea”).

Joaquin had the last word on Villa in his article, Doveglion and Other Cameos:

English will always be a part of the Philippines because a Filipino genius like Villa wrote in it, just as Spanish will forever remain rooted in this land because a Filipino genius like Rizal used it.”

Touché!

A career diplomat of 35 years, Ambassador Virgilio A. Reyes, Jr. served as Philippine Ambassador to South Africa (2003-2009) and Italy (2011-2014), his last posting before he retired. He is now engaged in writing, traveling and is dedicated to cultural heritage projects.

More articles by Ambassador Virgilio Reyes, Jr.