8 Contemporary Artists in the Wake of The Manila Galleons

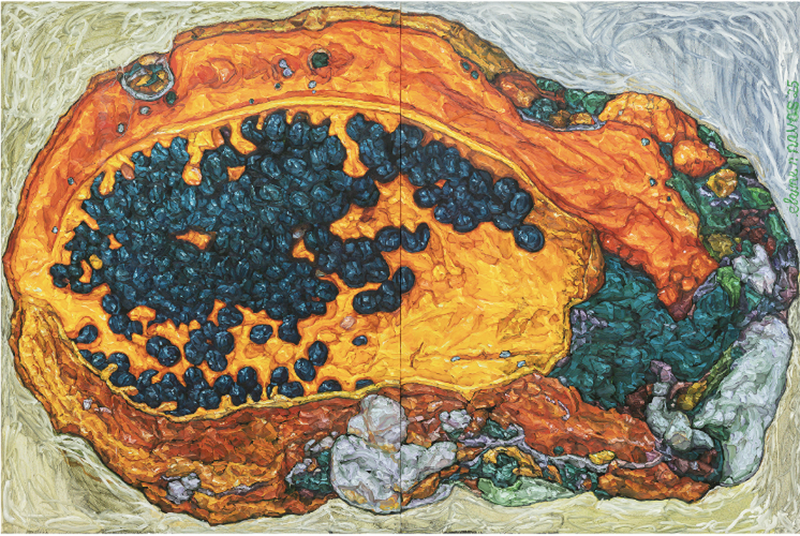

/Patrick Martinez Birds of a Feather (2025)

chickens, cows, pigs, up to one thousand souls

depending on whether the ship had a tonnage of 300 or 500

or 1,000 or 2,000, ships that in the 250 years

of the trade route wrecked somewhere along the way

more often than they arrived in Acapulco, sailors,

mercenaries, officers, noblemen and their entourages, priests

and missionaries, slaves that were called indios

or chinos, nails, tools, iron cask hoops, fireworks, opals — elegy?

- Rick Barot, The Galleons (Milkweed, 2020)

Barot’s evocative poetry about this early instance of globalization linking Asia to Europe and the Americas with Manila as hub, tries to bring to life the complex human stories missing from “official history.” Although the Manila Galleons’ main function was to extract commercial plunder, they also took a human toll that radically altered social structures and identities.

The trade route’s ultimate destination was Sevilla, but Galleon Trade at Silverlens New York is not a celebration of imperial geography, and there are no art works from contemporary artists from coastal Spain.

At the heart of Silverlens’ curatorial thesis is grief from the invisible, traumatic lines of connection etched in the historical memory shared by Mexico, the Philippines, and their respective diaspora communities in California. As material goods were traded along with cultural aesthetics, ideas, and people, the works of eight contemporary artists express inherited markers of identity.

***

Silverlens New York is located next to the former elevated train tracks known as the High Line. The movement of strollers up above breaks the gallery’s stillness as one enters the vestibule. Three white walls open to a long corridor leading to a larger light-filled room with a 20-foot ceiling. Patrick Martinez’s (b. 1980 Pasadena, California) neon quetzal bird against a riotous bougainvillea hue beckons at the far end of the hall.

However, to make sense of the connections between the works of art on display, it’s necessary to slow down and formulate a viewing strategy. The artists here (Carmen Argote, Patricia Perez Eustaquio, Jorge Rosano Gamboa, Patrick Martinez, Elaine Navas, Bernardo Pacquing, Carlos Villa, and Jenifer K Wofford) come from the Philippines, Mexico, and California and work in a wide range of media (e.g. abacá, corn husk, linen, house paint, found objects). One risks missing the point that the framework of the Galleon trade unifies them. Some lead questions are helpful.

How do these works of art convey the human cost of material plunder?

To the right from the vestibule is Bernardo Pacquing’s (b. 1967 Tarlac, Philippines) Stowaway (2025). The textured surface of this oversized work is made from found materials and a thick layering of house paint meant to mimic the worn hull of a ship. A rope hangs beyond the canvas onto the floor inviting one to grab it, although the red and black “rat guard” (meant to prevent rodents from entering the ship’s hold and damaging goods) prominent and menacing on the canvas, keeps it beyond reach. The work’s title Stowaway implies that the goods are welcome aboard for the passage, but those who loaded them are not.

On right, Stowaway (2025) by Bernardo Pacquing

To the left from Pacquing’s work, down the corridor, is Carmen Argote’s (b. 1981 Guadalajara, Mexico) work. The artist has twisted together what looks like three worn-out, damp-looking jackets gathered from the streets of urban Los Angeles. Shaped like a lifeless fish, the various parts are kept together by braided corn husk. The composition’s colors suggest decay, of thrown-away fashion washed up on the beaches of Ghana, the bits of red polyester pocket fabric poking out, turned inside out and empty. The dried corn husks, desperately trying to keep the composition together in frantic knots, are choked by gray plastic zip ties.

The corn husk can be seen as a reference to the decimated livelihoods of Mexican corn farmers due to the importation of heavily subsidized corn from the United States. It also relates to Pacquing’s rope and Patricia Perez Eustaquio’s (b. 1977 Cebu, Philippines) braided abaca installations, Fountain 007 (2024) and Fountain 002 (2024) calling to mind twine or rope, which can bind together, but also enslave.

On right, Carmen Argote's jackets from mom/Domestic Familial (2022)

Patricia Perez Eustaquio Fountain 007 (2024) woven from abacá

What are the elements of a shared visual language in the works of these artists as inheritors of the Galleon Trade?

Straight ahead to at the farthest wall is an oversize canvas of greens and blues against fuschia. Patick Martinez’ Birds of a Feather (2025), first seen upon entering the Gallery, features Filipino machuca tile and elements of Mesoamerican iconography from Cacaxtla in Mexico overlaid on stucco, crumbled and scorched at the edges. This palimpsest recalls elements of residential architecture, playing with ideas of home in a work of art that both celebrates and mourns visual elements that define the diasporic communities of urban Los Angeles.

“As material goods were traded along with cultural aesthetics, ideas, and people, the works of eight contemporary artists express inherited markers of identity."

How did artists try to rebuild identity after colonial erasure?

There are more pinks and greens in San Francisco-based Jenifer K Wofford’s You Dreamed of Empires (Morro Bay) (2025). A composition in surreal colors, it depicts a peaceful sunset over an empty basketball court, golden yellow next to a placid bay located on the Central Coast of California. The benign presence of a tall rocky outcrop stands guard. Morro Bay was the first recorded landing point of Filipinos in the Americas in 1587, where crewmembers were killed by indigenous Chumash. The tranquility of this scene contrasts with this first violent encounter.

Jenifer K Wofford You Dreamed of Empires (Morro Bay) (2025)

Notably, Wofford was a student of the iconic Carlos Villa (b. 1936, San Francisco, CA) whose works are also featured in the exhibit. Famously, Villa had asked his teacher about Philippine art history when he was a student at the California School of Fine Arts in 1958, but instead of admitting ignorance, the teacher replied, “Filipino art history doesn’t exist.” Villa went about reinventing it.

Carlos Villa, Space Case (1980)

Elaine Navas Bulok (2025)

***

Galleon Trade at Silverlens brings storytelling to contemporary art in an unapologetic attempt to remind us of ways of life already much faded from collective consciousness. The very real imprints–cultural, material, and human– left by the Manila Galleons in the cities it traversed are still visible today, though inevitably transformed by time and increasingly difficult to recognize.

***

Galleon Trade was curated by Susana V. Temkin.

More information on Silverlens and their galleries in both New York and Manila can be found here: https://www.silverlensgalleries.com/

In New York City from September 4 - 7 2025 Silverlens will be at The Armory Show with highlights from artists Pacita Abad, Emily Cheng, Keka Enriquez, Pow Martinez, and Ryan Villamael.

Jorge Rosano Gamboa Nenepilli - lengua del pacifico (2025)

Maria Victoria Yujuico writes about the intersection of art and literature with modern life.

Her master's thesis in Spanish and Latin American Literature, Problemas en torno al Boxer Codex: hibridez, etnografía y feminismo, highlights the relevance of the Boxer Codex to contemporary Philippine identity, examining the ways in which it both preserves and obscures pre-hispanic culture.

More from Maria Victoria Yujuico