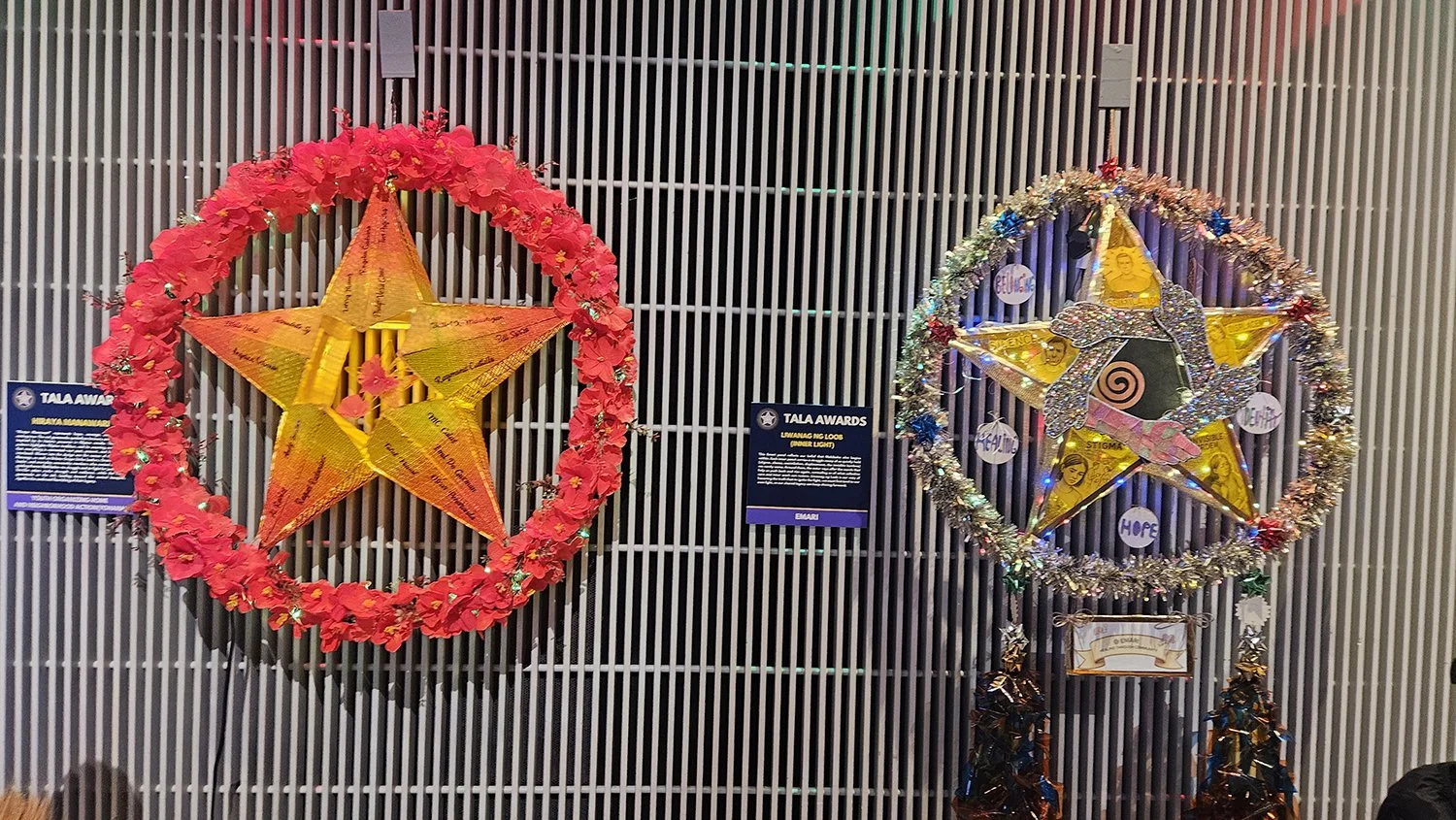

Alfafara Women

/(L-R) Primitiva Alfafara-Padin, Natividad Alfafara-Enriquez, Natalya Alfafara-Sarmiento, Julia Alfafara-Campañon and Catalina Alfafara-Nemenzo

Read about Celestino Alfafara here: http://www.positivelyfilipino.com/magazine/celestinos-crusades

The Alfafara women of Carcar, Cebu were known for their dominant presence in various aspects of small-town living. They were the entrepreneurs, the educators, the religious scolds, the no-nonsense homemakers, the excellent cooks, the opinion leaders, the storytellers, the fount of information, the domineering wives and the original stage mothers. In other words, they were alternately revered and better avoided, depending on one’s status in life and one’s latest deed. (Woe to the person who had displeased any one of them.) Because of this reputation, according to my first cousin Alice, Carcareños coined a phrase – Alfafara-hon – which in Cebuano means “like the Alfafaras,” meaning in this case, dominant and bossy.

The clan is huge and at some point in the late 19th- and early 20th century, controlled the politics and the economic structure of the town. My nephew John Ada has the details of this family history, and I’ve only heard snatches so I’m not going into that here.

The women in this picture, except for Tia Juling Alfafara-Campañon (second from the right next to my mother) who I didn’t get to know very well because she stayed in Carcar, loom large in my childhood memories.

Mama Idad (second from left) was my mother’s eldest sister while Mama Tiba (on the left) and Tia Talya (middle) were their cousins. Their children were sent to the University of the Philippines (UP) for college, and since there were several of them and they graduated in different years, each one of my aunts would come to stay with us in our campus cottage whenever graduation came around, which was usually in April. That’s when my summers became fiesta time, not just because they’d be bringing lots of Carcar delicacies, but they would also cook up a storm.

I particularly remember one summer – perhaps it was 1959 – when all three of them came at the same time. We had ampaw (crispy rice squares), mamon (butter cake), mangoes, bo-ongon (pomelo), shredded coconut balls and other Carcar goodies to our hearts’ content and enough inasal (Cebuano roast pork) and chicaron (pork rinds Carcar is famous for) to clog our arteries. For me, it was Christmas and heaven in one fell swoop.

Our suddenly busy kitchen would exude the aroma of lard, garlic and the multifaceted scents of the super-tasty dishes for days. Best of all, my notoriously talkative aunts garnished their cooking with luscious tales of small-town scandals peppered with raucous laughter, stories that fueled my imagination and delighted my senses, even if I didn’t know the people they were talking about.

My father and my uncles (my aunts’ husbands) could only shake their heads in amusement. I remember my father wondering how the three women who would see each other practically every day in Carcar could still manage to talk through the night when they were together in UP. My mother, the quiet one, who was involuntarily alienated from the Alfafara sisterhood because we moved to Quezon City, would only laugh with delight.

These aunts are long gone now, but true to their characters they passed away in style. One planned her funeral to the minutest detail, writing down her instructions in a notebook that had become worn out when she finally died. At her actual funeral, my uncle had to consult the notebook to see to it that her orders were followed to the letter, a pledge he had to make to my aunt before she died.

Another had her funeral saya (gown) made-to-order many years before she passed and would occasionally try it on and order alterations, to make sure she would look her best while lying in state.

I’m very sure my cousins have a lot more stories – both funny and scary – about the Alfafara women, but perhaps they’re better left to be enjoyed during clan reunions. One thing we know for certain though is that the blood that runs through our veins is the blood of women warriors and we are all the richer for it.