Beyond the Pandemic, Anti-Asian Hate Looks Awfully Familiar

/Executive Order 9066 and its companion Public Law 503 sent more than 120,000 Japanese-Americans to internment camps in 1942.

California was the only state in the Union to repeal anti-miscegenation laws targeting Asians and other minorities before 1950.

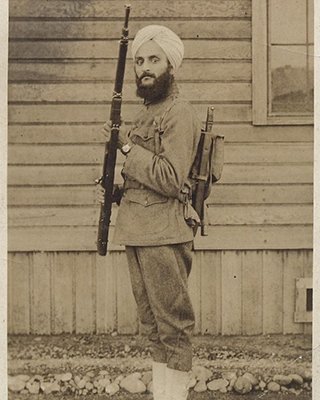

United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind barred Indians from U.S. citizenship.

Bhagat Singh Thind

The Philippine Independence Act of 1934 became a euphemism for the Tydings-McDuffie Act, a federal law that reclassified Filipinos as aliens despite the Philippines’ then-status as an American colony.

Nothing in the long list of Twentieth Century injustices is still on the books. However, those old laws live on as historical warnings that because they once had popular support, xenophobic actions should always be regarded for their potential to snowball and run roughshod over the rights of defenseless people.

How Anti-AAPI Hate Violates Civil Liberties

In the first quarter of the Twenty-First Century, Asians gained some respect. The agent of change was a merciless virus (cynics might add the growing power of Asians as a voting bloc). In 2021, President Joseph Biden signed the COVID-19 Hate Crimes Act that allocated grant funds and strengthened laws to protect Asian-Americans who are being scapegoated as cause and carrier of the pandemic.

Having the federal government acknowledge anti-Asian Hate as a growing crisis is better than a symbolic gesture. It gives Asian Americans validation as citizens whose lives and property are entitled to the same protections as other Americans.

According to Rose Cuison-Villazor, Professor of Law and Chancellor’s Social Justice Scholar at Rutgers Law School, “The law should be a platform for achieving social justice. But throughout history, the law has also been an instrument used to subordinate marginalized people.”

Rose Cuison-Villazor (Photo courtesy of Rose Cuison-Villazor)

Professor Cuison-Villazor teaches property law, immigration law, and race and the law. She is on a one-year sabbatical from Rutgers Law as she completes a fellowship at New York University School of Law. While at NYU, she is writing a book about federal laws that prohibited American men from marrying Japanese women between 1945 and 1952. Marriage would have given Japanese women the ability to apply for admission to the U.S. at a time when Japanese were not racially allowed to immigrate to the country.

Cuison-Villazor and her mother, Carol Smith, were born in Tarlac, Philippines. At age 11, her family immigrated to the Northern Mariana Islands, a U.S. territory. Her late father, Pablo Cuison, was from Pangasinan.

She has a lawyer’s sensitivity to nuance in her remarks, but she stands firm in her conviction that “Anti-Asian Hate is a form of racism. Targeting Asians violates civil rights laws and harms all communities of color. We therefore must pay attention and encourage both federal and state governments to continue supporting the AAPI community.”

Actions that she recommends to combat anti-Asian hatred are practical and realistic. As a full-time professor for 17 of her 51 years of age, she understands, “Federal and state laws have different definitions of what constitutes a hate crime. It is challenging to come up with a uniform legal definition. A different, effective response would be to work toward achieving a more holistic and cooperative and cohesive relationship between government agencies on a city, state and federal level.

“As Asian Americans, we must continue to be engaged politically so that our concerns aren’t ignored.” She says, “Filipinos can advocate for greater resources to support programs that address anti-Asian Hate.”

The Plight of Filipino World War Veterans

Keeping Asians safe is a priority. Cuison-Villazor is also concerned for Filipino veterans who are being denied national recognition and promised benefits for American troops during World War II. She realizes that Filipino veterans should be “entitled to certain federal benefits because the soldiers were either conscripted into fighting or volunteered to fight for the United States when the Philippines was a U.S. territory prior to the Japanese invasion.”

“The law should be a platform for achieving social justice. But throughout history, the law has also been an instrument used to subordinate marginalized people.”

She states, “Filipinos should encourage Congress to pass a law that would recognize the sacrifice that Filipinos did during the war and ensure that they receive the benefits they are entitled to.

“They should, at best, be given recognition by the Unites States for their sacrifices.” Yet, she realizes, “Sadly, the majority of them have either died or will die before the government acts on their behalf.”

Her desk faces a poster of the “Positively No Filipinos Allowed” hotel sign, circa 1930, in Stockton that reminds BIPOC persons that less than a hundred years ago, they were unwelcome even in the most progressive state in the U.S.

“The poster gives me a greater awareness every day that our history represents a large component of our identity as a people. ‘Positively No Filipinos Allowed’ is a reminder of the struggles that our predecessors faced in gaining recognition as Americans and to be considered part of the American polity.”

“Positively No Filipinos Allowed.” (Photo by Sprague Talbott)

Some Fil-Ams risked their lives eight decades ago to protect the freedoms that are embedded in the American character, but they still haven’t received respect for their sacrifices.

Positively Filipino Staff Correspondent Anthony Maddela has been assigned to contribute to the body of knowledge about Anti-Asian Hate as it relates to Filipinos.

More articles from Anthony Maddela