An Australian Connection: A Father and Daughter's Journey

/The talk at the May Manila women’s Forum (MWF) meeting was given by Marie Silva Vallejo, who grew up in Manila not knowing anything about her father Saturnino Silva. This is the untold story of Marie’s father Saturnino* and Marie’s journey of discovery. (*Henceforth in this article Saturnino Silva will also be referred to as simply Saturnino or Marie’s/her father. ~ Ed.)

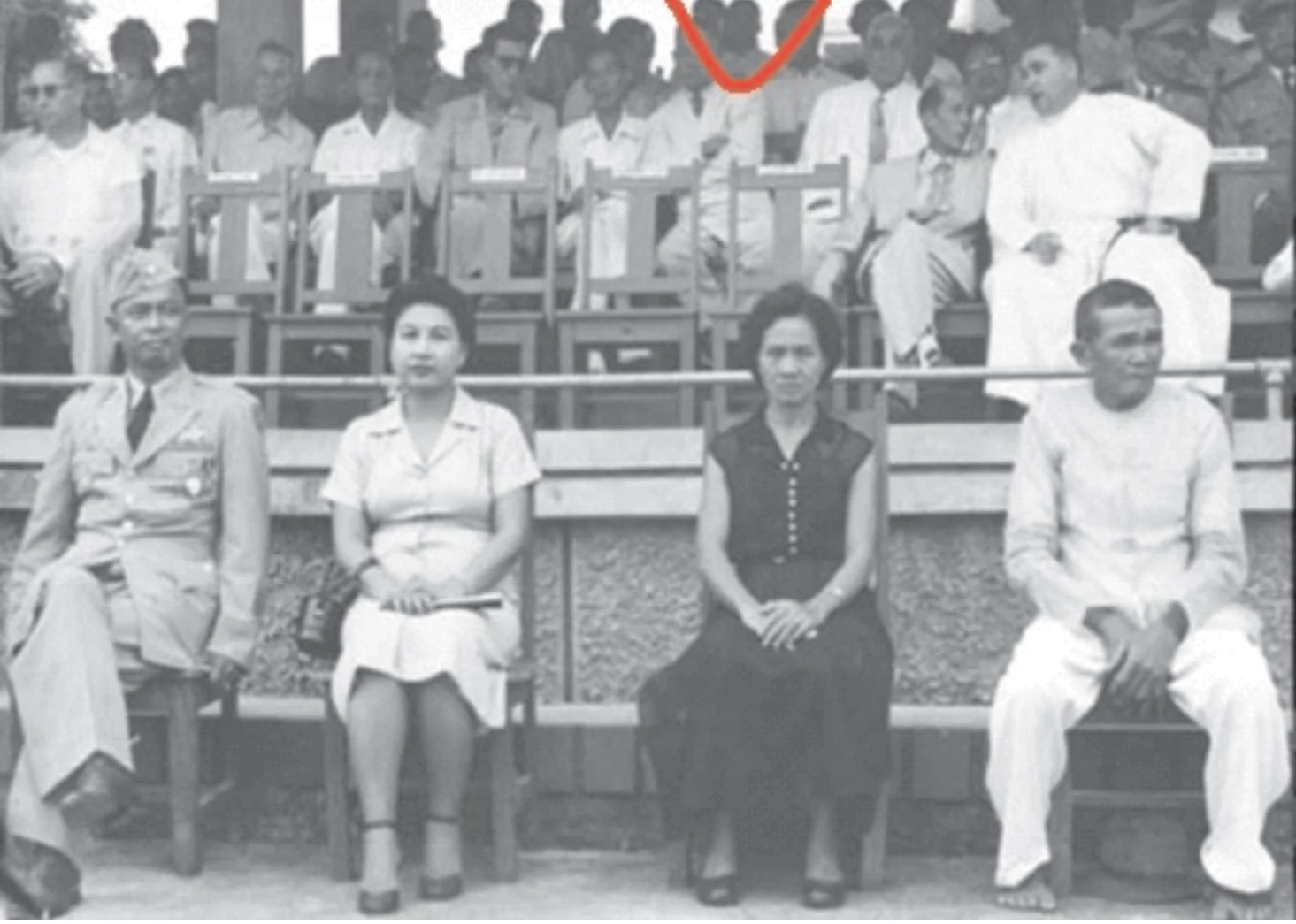

Major Silva (sitting on the left in uniform) on the occasion of his awarding by the Philippine Legion of Honor for his role in the Battle of Ising. MWF speaker Marie Silva Vallejo is in the shadows inside the red curve. (Source: the MWF Newsletter)

Thirty years later Marie’s father passed away without her knowing much about what he did as a soldier. Many years later, she retired from a corporate career in the US and moved back to Manila for her husband’s work. After a year of settling in Manila, her niece sent her a brochure from the city of Carmen in Davao that described the Battle of Ising (Carmen was named Ising before the war). When Marie learned that the man who led the battle was her father, she decided to find out more about what he did before and during World War II.

Marie found out that after working as a school teacher in the southern island of Tawi-Tawi, Saturnino went to Manila in 1929 and took a ship to Vancouver, Canada and then went to San Francisco to work in the vegetable fields of California. After several years of doing that, he found work as a secretary/assistant to a professor at San Francisco State College and worked while earning an Economics degree. Filipino men could not marry white women in those days, and there were very few Filipinas in California, so her father spent his spare time socializing with other bachelors. Marie showed us a photo of her father as president of a bachelor’s club in January 1941.

Thirty years of age and single, Saturnino joined the US Army as a private in April 1941, just months before the Pearl Harbor attack and the declaration of war by the United States. In order to allow the Filipinos in the United States to fight in the war, the US Army conducted a mass naturalization of over 2,000 Filipino men in 1943. That was the first generation of Filipinos with American citizenship and Marie’s father was one of them. Saturnino joined the 1st Filipino Battalion that later grew into a regiment. When a weak radio message from the Philippines was able to reach Australia, 400 men were chosen to go to Australia to undergo rigorous training in radio and jungle warfare for secret submarine missions.

Five Filipino soldiers including Saturnino received special orders to go to Australia ahead of the 500 men who were chosen. They were the first Filipino group to arrive and their goal was to transform a secret site 50 miles outside Brisbane in Australia into a military camp. Saturnino was second in command of the unit that provided trained radio operators for the missions. These men formed coast watcher stations upon arrival in the Philippines to monitor the major sea lanes around the islands. If they spotted an enemy ship, they would send a radio message to the US Navy, which in turn would sink the enemy ship.

Marie also discovered at this time that she had a half-sister named Isabel who was born after her father was sent to Australia and met and married a woman named Priscilla. Priscilla and Isabel were the names she found in her father’s briefcase when she was nine years old. It took six months for a marriage approval from General MacArthur because he did not want his men on special missions to have too many weaknesses or vulnerabilities. On a visit to Australia, she went through the telephone book’s entire page of Cunanan surnames looking for them. No luck. Later, she found out that their names were spelled as Conanan. As soon as the Internet became available, she searched for her father’s and their names. After many years, a 6-year old email between a mother and daughter surfaced; they were looking for the same man. There was an exchange of their father’s photo and of each other. One look and no DNA testing was needed to know they were related.

After mere days into the marriage, Saturnino was ordered to leave on board a submarine to go behind enemy lines in the Philippines. He was sworn to secrecy, and Priscilla will not connect with him again until two years later when the war ended. Isabel never met her father.

In February 1945, the Battle of Manila ended with the city destroyed and 100,000 civilians killed. Mindanao was the next target and the last to be liberated. Then Major Saturnino Silva assumed command of the 130th Infantry Regiment of 1,500 men in northern Davao. Some of the guerrillas were as young as 16 years old and many had lost everything – families killed, land and food crops taken by the enemy, no money and no clothes. The Americans landed in Cotabato on the west coast of Mindanao and marched east across the island to Davao City in two weeks.

While the Americans were liberating Davao City, the Battle of Ising began 36 kilometers north of the city. Major Saturnino Silva led his regiment in stopping a Japanese garrison by the National Highway from escaping to northern Mindanao. Clearing this National Highway hastened the liberation of Mindanao and prevented further atrocities by the enemy. The guerrillas were so proud that they overran the enemy without American ground support that they included in their brochure and did a re-enactment of that courageous time On the 4th day of the battle, Major Saturnino Silva was hit by a sniper’s bullet that shattered his left leg

For Marie, more pieces of the puzzle fell into place. The photo of the Boy Scout that she found in her father’s drawer was that of her half-brother Saturnino Silva, Jr. whose mother and Marie’s father were together during the short time he was in Mindanao. After he was wounded, he was immediately shipped back to the United States. There was no time for goodbyes with Junior’s mother who was pregnant with Junior. Like Isabel, Junior never met their father. When they all finally met, Marie and her brother John shared stories with Isabel and Junior about what their father was like and how they experienced growing up with him. Isabel said, “I am no longer alone.”

Left to right: Marie, Isabel, Saturnino Jr., and John. (Source: the MWF Newsletter)

Major Saturnino Silva received the Purple Heart for having been wounded in action. For bravery in action, he received the Bronze Star Medal. From the Philippine government, he received the Philippine Legion of Honor Medal. And out of the 7,000 Filipino men who joined the 1st and 2nd Filipino Infantries, he was the only one to have led a regiment of 1,500 men into battle.

There is a Veterans Memorial Shrine for the Battle of Ising in Mindanao but hardly anything is written about Mindanao in WWII. Marie put together a project team composed of volunteers who interviewed 22 veterans about their personal experience of the battle. She compiled these into a book so that their voices will be heard and they can show their pride in telling their stories. The book is titled “The Battle of Ising: The Untold Story of the 130th Infantry Regiment in the Liberation of Mindanao and the Philippines.”

Copies of the book were distributed to schools in Mindanao so that they may include the story in their teaching material. Marie also mounted an exhibition on the Battle of Ising in Davao so that the public may finally learn about this battle that was documented by the US Army as one of the most important and decisive battles of the guerrillas in the liberation of Mindanao.

The book The Battle of Ising: The Untold Story of the 130th Infantry Regiment in the Liberation of Mindanao and the Philippines (1942-1945). Author: Marie Silva Vallejo / MWF Speaker, 2016 May.

While doing the research for her book, Marie discovered a hidden gem of Philippine WWII records at the US National Archives in Washington DC. Filipinos and the rest of the world do not know much about these records and the stories that they tell. Many are unknown and may affect what we now know of Philippine WWII history. Most of the papers are crumbling with age, having been buried and exposure to the jungles of the Philippines To save these deteriorating records, Marie was grateful to have found the Philippine Veterans Affairs Office, the Filipino Veterans Foundation, and a private individual to pay for a team to digitize 270 boxes of Guerrilla Recognition Files that contained 280,000 records. Still, there are hundreds of boxes of records left to be digitized. Hopefully, a phase two of the project will start in 2017 to scan thousands more

After the records were processed, they were sent to Missouri where they can be used to verify claims for compensation. The 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act authorized a one-time payment from the Filipino Veterans Equity Compensation Fund to Filipinos who served in the Philippines. Those who are US citizens receive $15,000 while non-citizens receive $9,000.

Marie urged us to document and share our stories with future generations. We wish her good luck in continuing to digitize the guerrilla records, a huge and important undertaking.

From the MWF Newsletter © 2016 by Manila Women's Forum (MWF). This article may be freely copied and shared as long as nothing is altered or omitted including this copyright statement.

The Philippine Veterans Affairs Office (PVAO), Filipino War Veterans Foundation (FILVET) and Mr. Francisco Licuanan whose father was an officer in the Philippine Commonwealth Army of the United States Army Forces of the Far East (USAFFE) funded a project team to go to the U.S. National Archives and digitize the records of the Philippine Collection in 2015. The Guerrilla Unit Recognition File records composed of 270 boxes were digitized resulting in around 270,000 scanned records. The goal was to bring back a copy to the Philippine and make known the guerrillas’ heroic contributions during World War II (WWII) thereby promoting pride and nationalism. These records will be an integral part of the Mt. Samat Center for WWII Studies and known as the BGen Francisco Licuanan Jr. Memorial Collection. They contain names of Filipinos who did not surrender and became guerrillas after the fall of Bataan and Corregidor. Civilians and Americans also joined or formed guerrilla units. Their untold stories are in their files and now provides information never known before.

The original goal was to digitize the entire Philippine Collection composed of 1665 boxes. With the project funded enough for 4 months, the team was able to digitize only the Guerrilla Unit Recognition Files. Hopefully a Phase II will continue the digitization of additional records.

Contact Marie Vallejo at gowhenever@yahoo.com for a talk on the collection. She will be in San Jose, CA in November 2016.

When not in the Philippines helping to promote the wonderful National Museum at MVP; Carolyn Gibson spends time in the Middle East namely Oman with a spot on the radio.